Will Campaign 2020 Promote Or Undermine Criminal Justice Reform?

When mass incarceration in America gets political attention, it’s often so the issue can be used as a cudgel to attack opponents. Thus, the president Twitter-shames former Vice President Joe Biden for his role in promoting the 1994 crime bill even as Donald Trump’s own history of hounding the Central Park Five is highlighted in “When They See Us,” director Ava DuVernay’s Netflix miniseries on the teens accused, convicted, imprisoned, and eventually exonerated.

When Democrats and Republicans cooperated on a criminal justice reform bill late last year that made modest changes in the federal system, they congratulated themselves for getting something done in gridlocked Washington.

But it hardly solved the problem. That’s the message of Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, or EJI. “The presidential election will be important setting the tone,” he told me at a recent appearance in Charlotte. “The hard work has to happen in North Carolina, in the state legislature on issues like sentencing, on issues like prisons, on issues like excessive punishment, and that’s true for every state in the country.”

We are at a time when the idea of punishment has overwhelmed the concept of rehabilitation, Stevenson said, as the U.S. prison population has grown since the 1970s from 300,000 to 2.3 million, with 6 million on probation or parole and 70 million with an arrest history, and “no one seems bothered by it.”

According to its mission statement, EJI is “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.”

Stevenson spoke of the children caught in the system, of the pipeline “from the schoolhouse to the jailhouse,” and of a reaction to crime that lowered the minimum age of trying children as adults, with sentences that could mean life without possibility of parole. “They will change,” he said. “That’s what being a child means.”

Though politicians have often touted their “law and order” bona fides and have been hesitant to step away from that image with policy that could make opponents question their toughness, the December bipartisan legislation was a “First Step,” as the bill was called, to address inequities that disproportionately affect African Americans, minorities and the poor.

In his criminal justice work, Stevenson said he has seen the results tragically play out as he represents the accused in a system that treats you better “if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent” and when he brings appeals before judges “more committed to finality than they are to fairness.”

In the crowded field of 2020 Democratic presidential hopefuls, many have listened to their party’s base and floated criminal justice proposals to build on last year’s bill, including Sen. Cory Booker’s “Next Step Act.” Booker tweeted about his plan’s sweeping reforms, which include eliminating the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences, ending the federal prohibition on marijuana, expunging records and reinvesting in the communities most harmed by the War on Drugs.

It also includes a provision to reinstate the right to vote in federal elections for formerly incarcerated individuals. “Blacks are more than four times as likely than whites to have their voting rights revoked because of a criminal conviction,” Booker noted.

That last issue made headlines when Florida Republicans, after the state’s voters overwhelmingly approved returning voting rights to former felons who served their sentences, proposed limits that would first require payments of all fees and fines, a caveat that would keep many disenfranchised, a move that some Democratic lawmakers compared to Jim Crow tactics, such as poll taxes.

Stevenson also drew a line from America’s history of white supremacy to its treatment of African Americans in the justice system, in a nation that could get comfortable with two and a half centuries of slavery and that, when it came to its Native American population, kept so many place names derived from their languages but “made the people leave.”

His Charlotte appearance was sponsored by the Levine Museum of the New South, which is exhibiting, through July 17, “The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America.” It’s a collaboration with EJI and its Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

“Slavery did not end, it just evolved,” said Stevenson, who has testified in cases that deal with, for example, racial bias in jury selection.

As Stevenson noted, important action is taking place in the states, with New Hampshire recently becoming the latest to abolish the death penalty. “While it will be important to hear how our candidates for president address these issues, it will be more important that we ask our state representatives to think about this problem of over incarceration, too many people in jails and prisons in states like North Carolina who are not a threat to public safety,” he said. “We spend a lot of money on jails and prisons that could go into education and health and human services and support for people who are vulnerable.”

And the voices of the vulnerable too often are the ones least heard in a noisy presidential political season. Yet Stevenson has hope. “Injustice prevails where hopelessness persists.”

Mary C. Curtis has worked at The New York Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Charlotte Observer, as national correspondent for Politics Daily, and is a senior facilitator with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Twitter @mcurtisnc3.

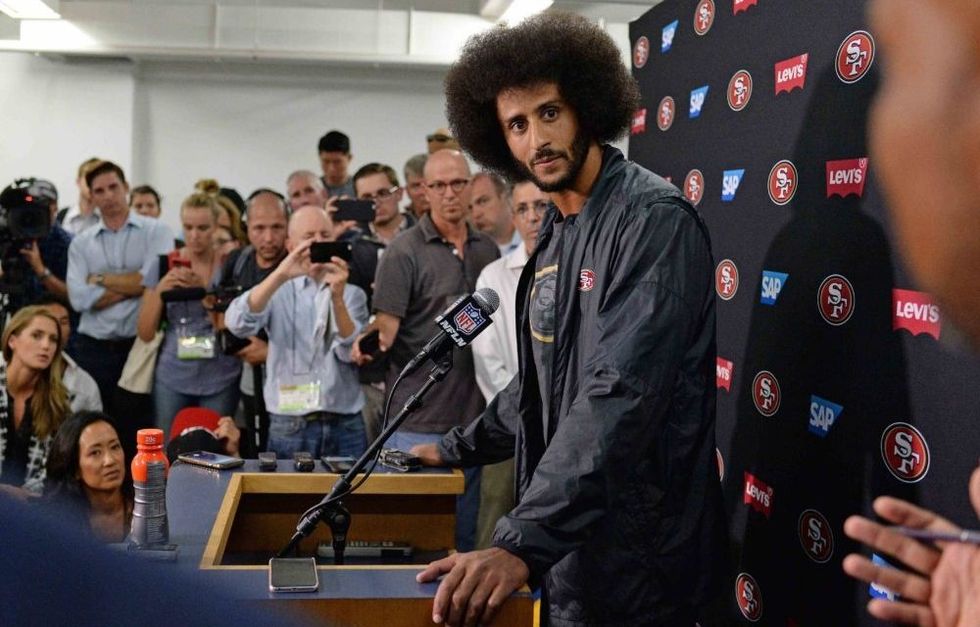

IMAGE: Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative.