Feeling Insecure At Work? That Fear Is Real -- And You Can Blame Trump

Groundhog Day's furry forecaster Punxsutawney Phil predicted six more weeks of wintry weather. What if we asked Phil to apply his insights to the frigid job market? He might answer the way an alarmed groundhog does, with chattering teeth, and then squeak, "Wheet! Wheet! Cold days are coming for American jobseekers, and they'll last a lot longer than six weeks."

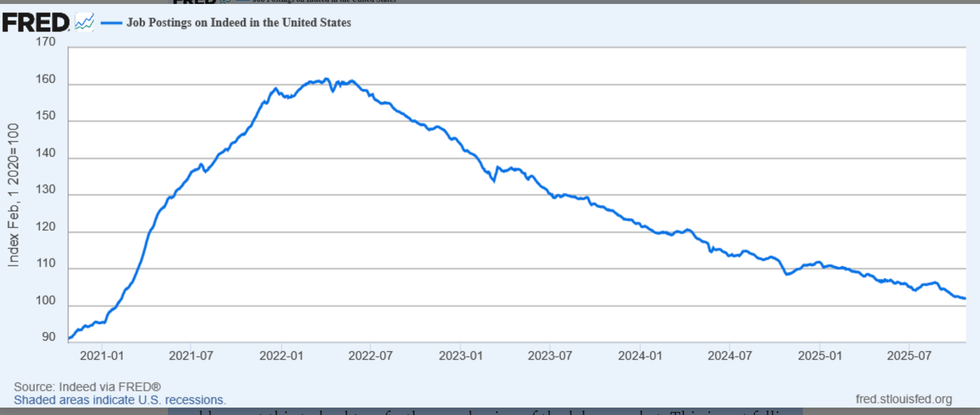

Economists are using the term "deep freeze" to describe the current job outlook. These are strange times. The official unemployment rate of 4.45 percent is not a distressing number, but the reasons behind it are worrisome. Many workers are sticking with their jobs, fearful they can't find a new one.

Aside from some big-headline layoffs, most employers figure business is good enough to hang on to the staff they've got, but not strong enough to take new people on. The main reason: They have no idea what exactly is going on in the American economy.

Is it fair to pin this unsettling situation on Donald Trump? Sure, it's fair, though he doesn't deserve all the blame. What he does, reliably, is make a lot of problems worse.

Start with the tariffs. His trade war — slapping higher duties on essentially the rest of the world — was sold as a job-creation engine. It hasn't worked out that way. Since "Liberation Day," April 2, 2025, U.S. factory employment has fallen month after month. And last year, the number of job openings dropped by nearly a million.

What tariffs have done is push up prices that Americans pay for food and other everyday goods. In other words, they add to inflation. Prices haven't spiked as dramatically as some warned, but they've risen enough to leave consumers uneasy and on edge.

American companies that obtain parts and materials from abroad are now paying more for them. Some have swallowed at least some of those added costs, but much of the tariff tax gets passed onto buyers. Many companies say they will now have to pass more of those costs to consumers.

Such disruptions have hit Main Street businesses especially hard. They are less able than big corporations to deal with the confusion over tariffs. Who is meant to foot the bill? Vendors? Purchasers? Shoppers? Small companies employ almost half the American workforce.

Then there's the immigration crisis. Roundups of undocumented aliens were supposed to free up jobs for Americans. But Trump's spectacle of ICE agents sweeping up the foreign-born has created a mess for local businesses. Both legal and illegal immigrants are afraid to go to work and shop at stores. Immigrants, after all, are also customers.

Artificial intelligence isn't Trump's doing, but it's here. Analysts expect American companies to pour more money into robotics and artificial intelligence — technologies that replace human labor. A bachelor's degree will no longer shield many college grads from unemployment, as AI moves in on work many well-paid professionals considered safe.

Anthropic's "AI Assistant," Claude, can now read, write and analyze text. It can take on some accounting tasks, such as reviewing documents and drafting reports.

As demand for humans with such skills shrinks, employers looking to add staff have become super picky. That's making life especially tough for young people trying to land entry-level jobs. The office outlook is scary: a small cadre of senior executives, the "C-suite," presiding over rooms of smart machines that can match, or even outthink, Homo sapiens.

Businesses don't know which way is up, down or sideways, and Trump's daily dose of chaos isn't helping. The mystery of what will come next leaves many companies hesitant to hire.

Winter is settling in the job market. If you're feeling insecure, you may be on to something.

Froma Harrop is an award winning journalist who covers politics, economics and culture. She has worked on the Reuters business desk, edited economics reports for The New York Times News Service and served on the Providence Journal editorial board.

Reprinted with permission from Creators.