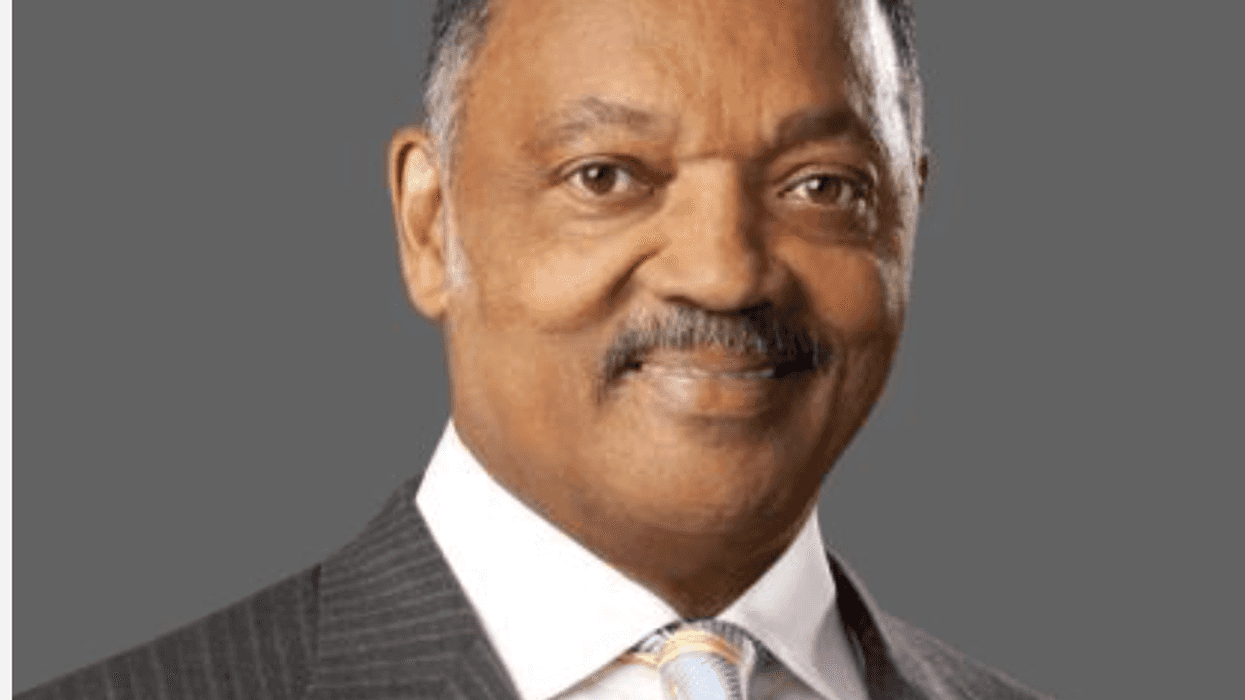

As We Fight The Battle Of Our Lives, Remember Jesse Jackson

It would be hard to overstate Jesse Jackson’s importance in opening up American politics and society, not just to Black Americans, but also to Hispanics, and the LGTBQ community. It is probably difficult for younger people to imagine, and even old-timers like myself to remember, how bad discrimination was in the not very distant past.

When Jackson ran the first time in 1984, and even the second time in 1988, there was not a single Black governor in the United States. There had been no Black governors since the end of Reconstruction. There were also no Black senators.

The only Black to serve in the Senate since reconstruction was a Republican, Edward Brooke, who was elected in Massachusetts. When Carol Mosley Brown got elected to the Senate from Illinois in 1992, it was widely noted that she was first Black woman to be elected to the Senate. She was also the first Black Democrat to be elected to the Senate.

It wasn’t just in politics; Blacks were largely excluded from the top reaches in most areas. I recall when I was a grad student at the University of Michigan in the 1980s. There were just two Black tenured professors in the whole university. There was a similar story in corporate America.

Jackson’s campaign didn’t turn things around by itself, but it certainly helped to spur momentum for larger changes. Back then people seriously debated whether a Black person could be elected president in the United States. Jackson’s campaign raised that question in a very serious way.

Barack Obama (the second Black Democrat to be elected to the Senate) answered that question definitively two decades later. While President Obama is obviously an enormously talented politician, without Jackson’s campaigns, it is hard to envision Obama ever having been a serious presidential contender.

And Jackson was serious about a “rainbow coalition.” He also helped open the door for Hispanics, for Arab and Muslim Americans, and for the LGBTQ community. At a time when there were no openly gay or lesbian members of Congress, and even liberals were afraid to be associated with anyone who was openly gay, Jackson stood out in offering a welcome mat.

Jackson also pushed a powerful economic message. At a time when Reagan was busy cutting taxes for the rich and cutting back social programs, and trade was devastating large parts of the industrial Midwest, Jackson was advocating a populist agenda that focused on building up the poor and the working class. His message resonated with many white workers who felt abandoned by the mainstream of the Democratic Party, and even many farmers who were devastated by an overvalued dollar in the early and mid-1980s.

There is a bizarre revisionism, that has gained currency among people who pass for intellectuals, that the baby boomers grew up in a Golden Age in the 1970s and 1980s. The unemployment rate averaged over 7.0% from 1974 to 1992. The median wage actually fell from 1973 to the mid-1990s. This was a period of serious upward redistribution and the losers, as in most people, were not happy campers. Jackson spoke to those people.

I had the opportunity to work in Jackson’s campaign in Michigan in 1988 and I still remember it as one of the high points of my life. Even though Jackson had vastly outperformed anyone’s expectations in the early primaries (probably even his own), he was not taken seriously in the Michigan race. Most of the pundits considered it a race between the frontrunner Michael Dukakis and Congressman Dick Gephardt, who had strong union support. As it turned out Jackson handily beat both, getting an absolute majority of the votes cast in the state.

In my own congressional district, which centered on Ann Arbor, all the party leaders lined up for Dukakis. The Jackson campaign was composed of a number of people who worked in less prestigious jobs, like salesclerks and custodians, and grad students like me. It really was a multi-racial coalition.

We managed to totally outwork the party hacks. First, because it was a caucus and not a primary, it meant that people would not go to their regular precincts to cast their votes. We made sure that our supporters had a neatly coded map that told them where their voting site was.

Also, since it was a caucus and not a primary, the state’s usual rules on being registered 30 days ahead of an election did not apply. We had a deputy registrar at every voting site who would register people who had not previously registered.

We also made a point of having all our workers knocking on doors on election day and offering to drive people to the polls who needed a ride. The Dukakis people were all standing around the voting sites, handing out literature with their big Dukakis buttons, apparently not realizing that anyone who showed up had already decided how to vote.

I remember talking to a reporter late that night after the size of Jackson’s victory became clear. Up until that point, there had been numerous pieces in the media asking, “what does Jesse Jackson really want?” as though the idea that a Black person wanting to be president was absurd on its face.

I couldn’t resist having a little fun. I pointed out that with his big victory in Michigan, Jackson was now ahead in both votes cast and delegates. I said that I think we have to start asking what Michael Dukakis really wants.

Anyhow, the high didn’t last. The party closed ranks behind Dukakis and he won the nomination. He then lost decisively to George H.W. Bush in the fall. His margin of defeat was larger than in any election since then.

All the gains of the last four decades are now on the line, as Donald Trump and his white supremacist gang look to turn back the clock. We have the battle of our lives on our hands right now.

But Jesse Jackson was a huge player in the changes that created the America that Donald Trump wants to destroy. He had serious flaws, like any great political leader, but for now we should remember the enormous impact he had in making this a better country.

Dean Baker is a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and the author of the 2016 book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Dean Baker.