How To Talk To Black People In Eight Easy Lessons

Today’s column is presented as a public service.

It is for serious politicians both Democratic and Republican — and also for Donald Trump. The urgent need for this service has been painfully obvious for many years and never more so than today. So, let’s get right to it. This is: How to Talk to Black People in Eight Easy Lessons.

1. Go where we are.

You’d think that pretty obvious. Then you remember Trump purporting to speak to black people whilst addressing audiences whose aggregate melanin wouldn’t fill a Dixie cup.

2. Don’t act as if going where we are requires machetes and a supply line.

“Some have said that I’m either brave or crazy to be here,” Republican Sen. Rand Paul once told a black audience. He said this at Howard University, which is about 15 minutes from the White House. They have cell service there and everything.

3. Stop confusing the NAACP with the Nation of Islam.

Donald Trump recently snubbed an invitation to address the venerable civil rights group. Bob Dole once did, too, claiming they were trying to “set me up.” Right. Because the NAACP has such a long history of incendiary rhetoric. As one of its founders, the great scholar W.E.B. DuBois, never really said, “I’m ’bout to bust a cap on these honkies if they don’t give me my freedom.”

4. Don’t use Ebonics unless you are fluent.

I still have nightmares about Hillary Clinton crying out, “I don’t feel no ways tired” in that black church in Selma. Stick to Ivorybonics. Most of us are bilingual.

5. Don’t make a CP time joke unless you are a CP.

When candidate Obama sauntered onstage about 15 minutes after the start time of a black journalists’ event and quipped, “I want to apologize for being a little bit late — but you guys keep on asking whether I’m black enough,” it was cool and funny. When Bill de Blasio joked in a scripted exchange with Hillary Clinton about running on “CP Time” — “cautious politician time” — it was, well, not.

6. Don’t make a slavery joke, period.

Joe Biden once warned a black audience that Republicans are “going to put y’all back in chains.” Can you imagine him warning a Jewish crowd how the GOP is “going to put y’all back in the gas chambers”? Can you imagine how offensive that would be?

7. Don’t talk to the black people in your head.

This is what Donald Trump was doing when he told black people they lived in the suburbs of hell and had nothing to lose by voting for him. He was speaking, not to black people, but to black people as he imagines them to be, based on lurid media imagery and zero actual experience. In this, he was much like Bill O’Reilly, in whose world black folks all have tattoos on their foreheads.

8. Know what you don’t know.

“I’m here to learn,” said Trump at a black church in Detroit a few days ago. It was a powerful expression of humility — or would have been, had it been said by someone who wasn’t an OG of the birther movement, a serial re-tweeter of supremacist filth and the star of David Duke’s bromantic fantasies. Still, he had the right idea. Politicians too often purport to lecture us about us without having the faintest idea who we even are.

The truth is, How to Talk to Black People isn’t all that difficult.

The candidate who wants African-American support should pretend black folks are experts on our own issues and experiences — because we are. He should learn those issues, tap that experience, formulate some thoughtful ideas in response. Then he should do what he would for anyone else:

Ask for our vote. Tell us what he’d do if he got it.

(Leonard Pitts is a columnist for The Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla., 33132. Readers may contact him via e-mail at lpitts@miamiherald.com.)

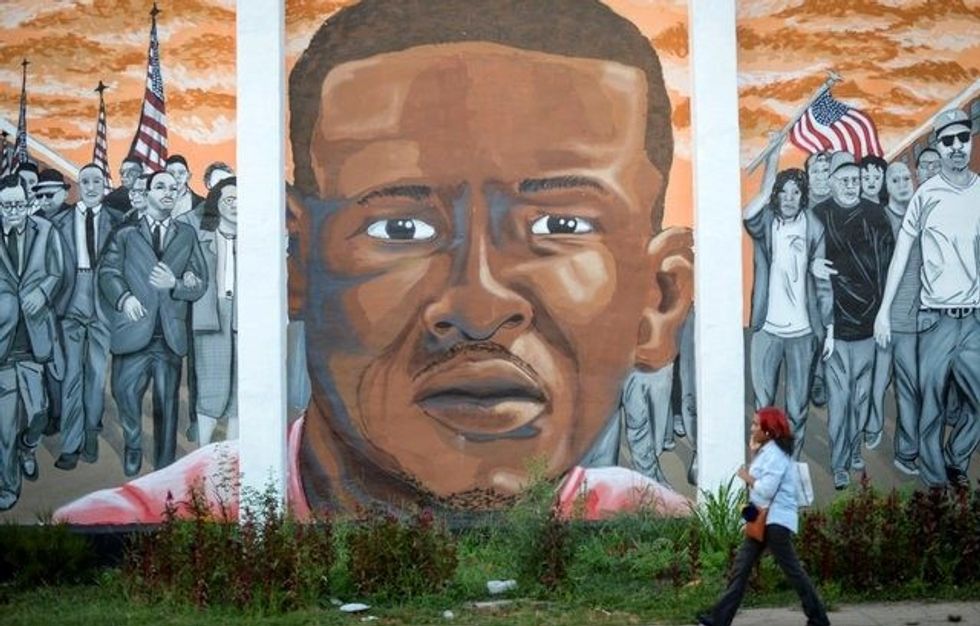

Photo: Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump attends a church service, in Detroit, Michigan, September 3, 2016. REUTERS/Carlo Allegri