'Untethered To Facts': How Portland Exposes Trump's Fake 'Emergencies'

District Court Judge Karin Immergut’s adroit opinion blocking the administration’s plan to deploy National Guard troops to Portland offers a model for how courts should handle the Trump administration’s many assertions of “emergency power.” The opinion is low-key but precise and judicious, and it points the way out of a legal thicket that has been growing denser with every new assertion of presidential emergency power. Most importantly, Immergut, a Trump appointee, insists on a critical constitutional truth in the age of Trump—one that other courts have yet to express: deference is not the same as blind acquiescence.

The case forced Immergut to confront the central pathology of the Trump era. Trump’s pattern of invoking “emergencies” has been prolific—and consistently mendacious. He has lied about imaginary “invasions” at the southern border, about “crime waves” in the District of Columbia, about fentanyl “floods,” and immigrant “armies.” Now he has invented a supposed “rebellion” in Portland to justify sending in troops under 10 U.S.C. § 12406—a statute that allows federalization of the National Guard when there’s an invasion, a rebellion, or when the President is unable, with the regular forces, to execute the laws.

Immergut, who lives in Portland, coolly explained that there was no insurrection. Portland was not “war-ravaged.” Protesters were not “domestic terrorists.” Local law enforcement was fully capable of handling the scattered incidents that did occur.

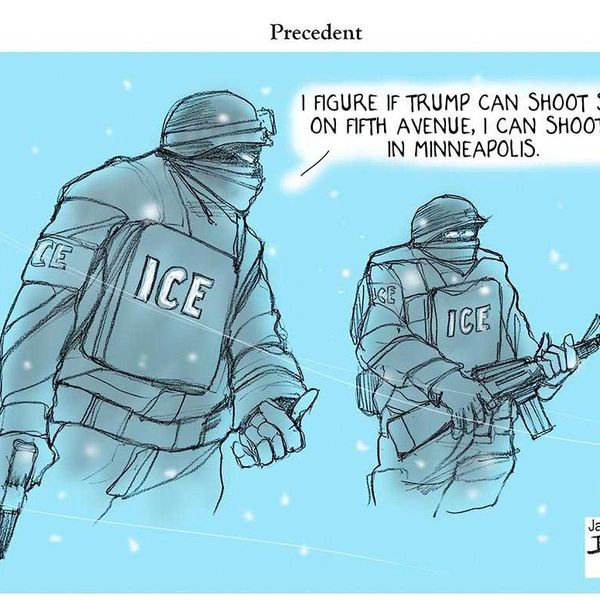

Trump has been prodigal in invoking “emergencies”—at the border, in cities, even in cyberspace—but nearly all have rested on transparent falsehoods. There has never been an “invasion” of marauding migrants, or a fentanyl “siege,” or a crime wave in Washington sufficient to justify federal deployment. Each supposed emergency has been a pretext for asserting powers Congress never gave him. The pattern is as consistent as it is brazen: declare a crisis, invent the facts to match, and dare the courts to stop him.

That poses a unique problem for courts. The judiciary has long applied doctrines of deference to the executive branch, giving “respectful weight” to the President’s factual determinations in national security or emergency contexts. The rationale is sound in principle: judges are not generals or intelligence officers, and they traditionally assume the President acts in good faith to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”

Trump has laid waste to that principle with his brazen willingness to serve up lies in patent bad faith. That reality changes the meaning and application of deference to the executive. It’s one thing to respect a president’s reasoning; it’s another to swallow the sensational fabrications of a carny.

Judge Immergut inherited a tricky legal backdrop. In State of California v. Trump, Judge Charles Breyer in the Northern District of California had earlier struck down Trump’s invocation of emergency powers to fund the border wall. Breyer found the statutory predicates unmet and the “emergency” itself fictitious. But a Ninth Circuit panel stayed—and later reversed—his TRO, in a terse opinion emphasizing a ‘highly deferential’ standard and leaving its limits unclear. Immergut met that fuzzy command with clarity, modesty, and backbone.

As in the Breyer case, the administration argued that the President had determined that Portland met § 12406’s criteria and that courts must defer to that determination. The implicit argument was that judges must bless even the most fantastical presidential claims so long as the word “emergency” appeared in the proclamation. Immergut refused to take that bait.

She began with the facts on the ground and their stark contrast with Trump’s hysterical assertions. Oregon and Portland had shown, she wrote, “substantial evidence that the protests at the Portland ICE facility were not significantly violent or disruptive.” The federal defendants, by contrast, produced nothing resembling proof of rebellion or organized resistance to federal law. “Sporadic violence,” she noted, “is not the same as a rebellion.”

Turning to the administration’s claim that Portland faced a “rebellion” or “danger of a rebellion,” her conclusion was unsparing: the President’s determination “was simply untethered to the facts.”

That phrase—“simply untethered to the facts”—is a gem. Immergut doesn’t rage or sermonize; she simply compares Trump’s public statements about “mobs,” “agitators,” and “paid radicals” with the actual record before her. The gap is abyssal. Her refusal to indulge the fiction is, in itself, a quiet act of civic courage.

The heart of the opinion comes when she addresses the administration’s inevitable fallback—that courts owe the President broad deference. She agrees, up to a point. A “great level of deference,” she writes, is indeed due to the executive’s factual determinations in matters of security. But deference does not mean ignoring the facts on the ground. Courts, she continues, must ensure that a presidential determination “reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a range of honest judgment.”

That is the key sentence—the one that should echo in every courtroom and chamber of the appellate bench. It reclaims deference from the edge of abdication. It draws a clean, bright line between a reasonable mistake and a deliberate falsehood. “The President’s determination,” she concludes, “was simply untethered to the facts”—that is, conceived in bad faith. Immergut doesn’t say “liar.” She doesn’t have to. The entire structure of her reasoning spells it out. She treats truth as the baseline condition for judicial respect. Without it, “deference” collapses into blind obedience.

Deference, she reminds us, exists within a tripartite system in which the executive has a reciprocal duty to respect judicial determinations. Trump and his aides plainly do not share that understanding. He insulted Immergut, saying she “ought to be ashamed of herself,” and doubled down on his fantasy tableau: “Portland is burning to the ground… all you have to do is turn on your television.” Stephen Miller, comically pompous as ever, took it further, calling the decision “one of the most egregious and thunderous violations of constitutional order we have ever seen.”

Far worse than the rhetorical attacks, the feds appear to have ignored Immergut’s ruling altogether. She convened an emergency hearing Sunday night and told DOJ lawyers that the President was “in direct contravention” of her order. She then stiffened the terms to bar “the relocation, federalization, or deployment of members of the National Guard of any state or the District of Columbia in the state of Oregon.” A fight is clearly brewing.

Immergut’s opinion arrives at a perilous moment. Trump has discovered that “emergency” is a magic word—one that can turn lies into legal justifications and personal will into governmental authority. If courts yield reflexively, he can continue to conjure crises out of thin air and claim martial powers to address them. Most ominously, he could try to play that card in the context of the midterms, proclaiming an emergency that lets him interfere with the machinery of democracy itself.

But Immergut’s approach shows how the judiciary can resist without crossing into partisanship. She doesn’t deny that presidents need latitude; she insists only that the factual predicates must fall “within the bounds of reason.” That formulation—at once moderate and profound—anchors her opinion in the deep tradition of the rule of law. It reminds us that facts are not partisan; they are the medium in which law lives.

Part of what makes the opinion so powerful is its tone. Immergut’s prose is calm. There is no self-dramatization, no flourish. Yet by doing nothing more than refusing to credit falsehoods, she performs an act of moral clarity that the country badly needs.

If other judges follow her example, they can begin to contain the metastasizing notion that presidential power grows in proportion to bad faith. The judiciary’s role is not to assume the truth of the President’s sensational fantasies but to ensure that factual predicates for emergency powers are real. And when district judges, who see witnesses and evidence firsthand, make those credibility determinations, appellate courts should defer to them—not to executive fiction.

There are sound reasons for doctrines of deference, but none that justify acquiescing in lies. Immergut’s decision shows that need not happen. She demonstrates that ordinary judicial virtues—care, honesty, restraint—are enough to halt extraordinary abuses. Fidelity to fact, she reminds us, is fidelity to the Constitution. The stakes of this case “go[] to the heart of what it means to live under the rule of law in the United States.”

“Deference” cannot be an automatic pass to lawlessness or a license to bypass constitutional rights. If courts wield the label of “deference” to greenlight emergency powers based on lies, the law goes dark. Immergut’s opinion lights the way out.

Harry Litman is a former United States Attorney and the executive producer and host of the Talking Feds podcast. He has taught law at UCLA, Berkeley, and Georgetown and served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Clinton Administration. Please consider subscribing to Talking Feds on Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Talking Feds.