How The Ultra-Rich Are Different From You And Me (And The One Percent)

On Wednesday the Wall Street Journal published an article with the headline “Billionaires’ low taxes are becoming a problem for the economy.” Hey, what do you expect from a woke, left-wing rag?

To be honest, the article didn’t make a very compelling case for its ostensible point, that the growing concentration of wealth at the very top may lead to economic instability. But it did offer a good discussion of both the soaring concentration of wealth in the hands of a tiny elite and of the extent to which this elite is able to avoid paying taxes.

Many discussions of inequality in America fail to grapple with the way we have become an oligarchy, with a large share of income, an even larger share of wealth, and a huge amount of political power accruing to a very small number of people. One still sees discussions of the “elite” that focus on the top 20 percent or the top 10 percent, when the real action is much further up the scale. Never mind the one percent. To understand what’s happening to us, we need to focus on the 0.1 percent, the 0.01 percent, even the 0.00001 percent.

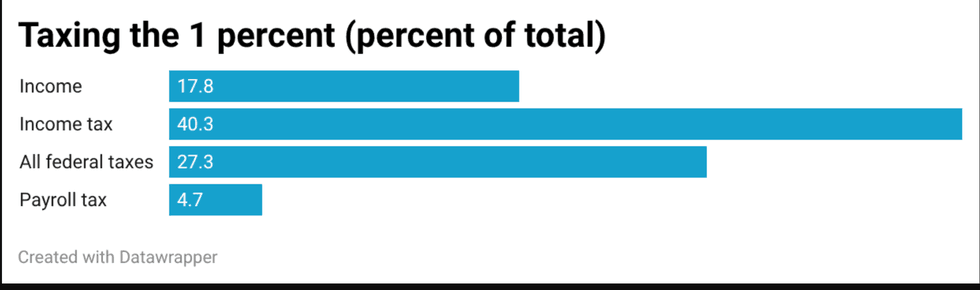

True, even the economic position of the top one percent is widely misunderstood. The Journal article misleadingly suggested that Americans in the top 1 percent as a whole are heavily taxed, because they pay 40 percent of income taxes. But the income tax isn’t the only tax! In particular, the federal government also collects a lot of revenue from payroll taxes, which fall much more heavily on low- and middle-income Americans than on the upper class. As a result, the top 1 percent only pays 27 percent of total federal taxes:

Furthermore, state and local taxes are strongly regressive:

Overall, the top one percent as a group pay at most a slightly larger share of U.S. taxes than their share of pretax income.

Furthermore, most people within the top one percent are what Leona Helmsley called “little people,” as in “Only the little people pay taxes.” The ultra-rich — the 0.1 percent, the 0.01 percent, the 0.00001 percent — pay much lower tax rates than the merely rich. I’ll explain how they pull this off shortly. First, let me make the point that it’s the ultra-rich, who account for only a tiny fraction of the one percent, who have been pulling away from the rest of the nation.

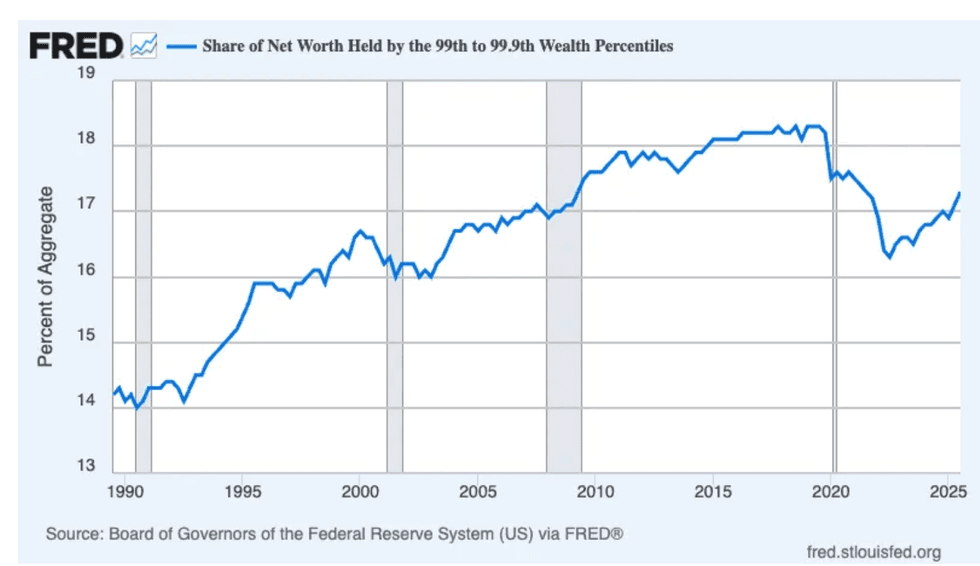

The data from the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts are startling. It turns out that the share of total wealth held by the merely rich — those in the top 1 percent but not in the top 0.1 percent — has actually declined since the 2010s:

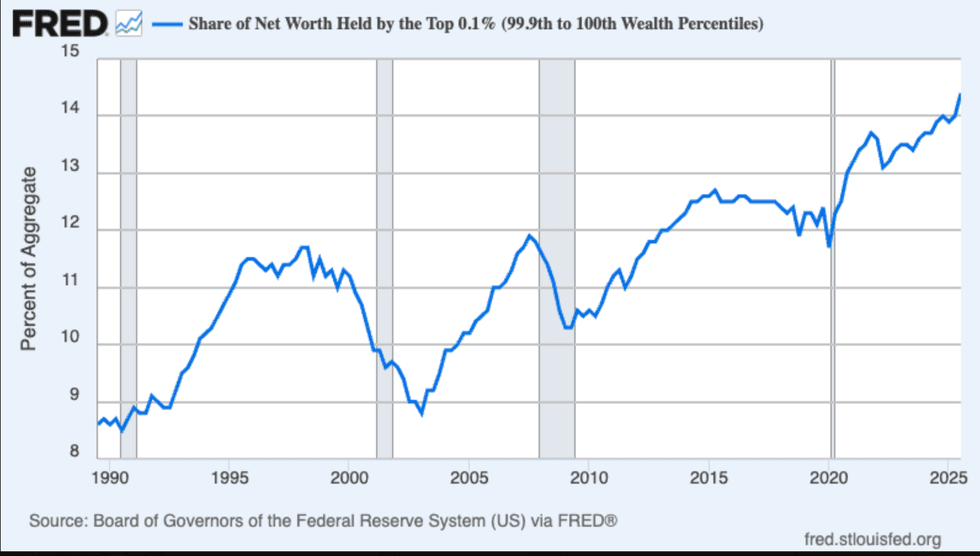

At the same time, the wealth share of the top 0.1 percent, the ultra-rich, has soared:

In 2022, the minimum wealth required to be in this category was $46 million. It’s more now.

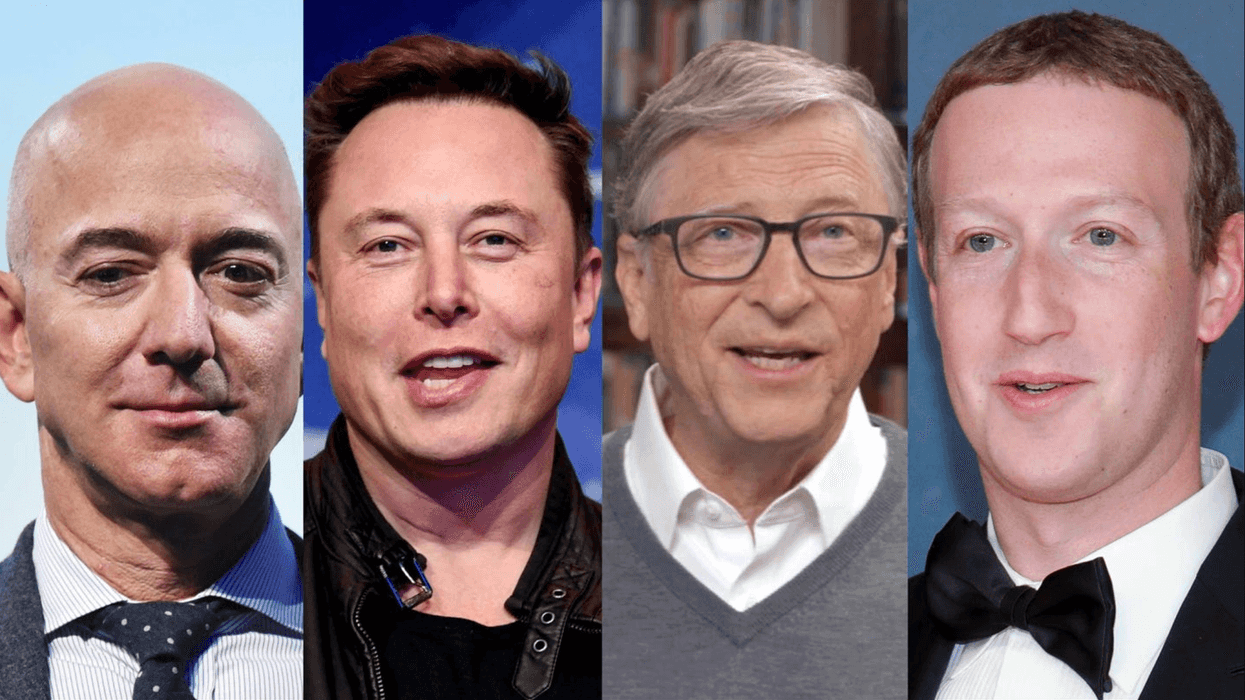

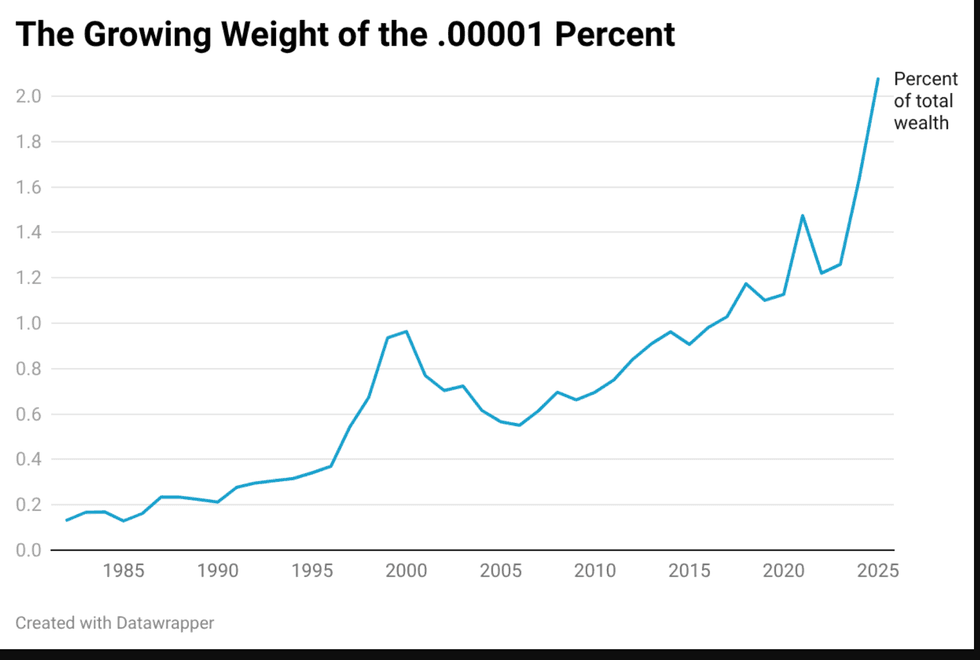

And much of the rise in wealth of the 0.1 percent is accounted for by the super-billionaire class, a tiny sub-group of almost inconceivably wealthy individuals. Reposting a chart from Wednesday’s post:

Why are the ultra-rich pulling away from everyone else? Partly because they pay much lower taxes than the little people. Some manage a full Leona Helmsley, paying no taxes at all. On average, according to recent estimates by Balkin, Saez, Yagan and Zucman, they pay a total tax rate — federal, state, and local — of only 24 percent. That’s less than the average for the whole population, around 30 percent. And it’s much less than the tax rate for “top labor income earners.” That means people who receive big paychecks — but who do receive paychecks. In contrast, the incomes of the ultra-rich flows largely from or through businesses they own.

Put it this way: The “$400,000 a year working Wall Street stiff, flying first class, and being comfortable,” mocked by Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street, pays around 40 percent of his income in taxes. The modern equivalents of Gekko — who make orders of magnitude more money than the financial predators Gekko was modeled on — typically pay only around half as much.

How do the ultra-rich pull this off? Most of their success at tax-dodging presumably reflects tax avoidance rather than tax evasion. Avoidance, as opposed to evasion, involves strategies that are legal, although they shouldn’t be. Balkin et al emphasize the way the ultra-rich arrange to ensure that most of their income accrues not directly to themselves but to businesses they control, and are able to benefit from their wealth without ever turning that wealth into taxable income.

The Journal notes one example:

Amassing assets like stocks, borrowing against them rather than selling during the owner’s lifetime, and passing them to the next generation after death is sometimes called the “buy borrow die” tax-avoidance strategy.

It’s clear that by any reasonable standard the extremely rich pay much less than their share in taxes.

Why doesn’t the U.S. government try to close the loopholes that allow the extremely rich to pay so little? Don’t say that it would be technically difficult or that it would hurt the economy. We were able to tax the rich for a generation after World War II, a generation during which the U.S. achieved the best growth in its history. In general, governments in advanced nations have enormous ability to achieve their goals, if they want to.

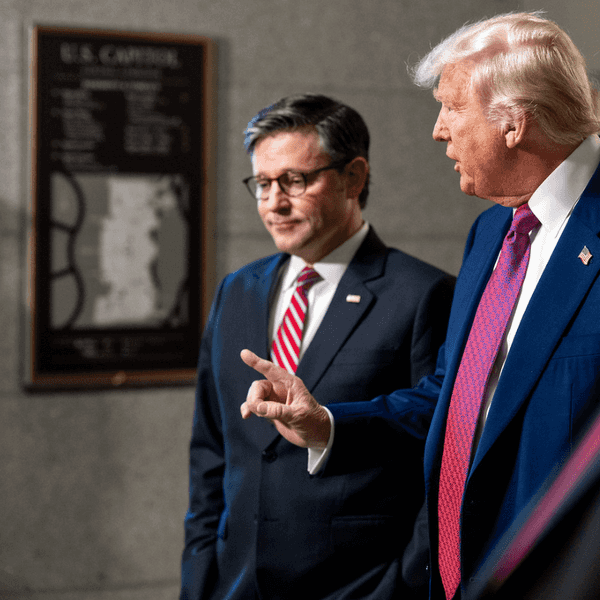

The problem, of course, is that too many politicians don’t want to collect taxes on the superrich, because the ultra-wealthy have used their wealth to achieve immense political power. And the failure to tax them effectively is reinforcing the vast accumulation of wealth at the top.

It’s a vicious circle. And whatever you think of specific proposals for wealth taxes and other approaches toward reining in America’s billionaire class, we had better take action before it’s too late.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Paul Krugman.