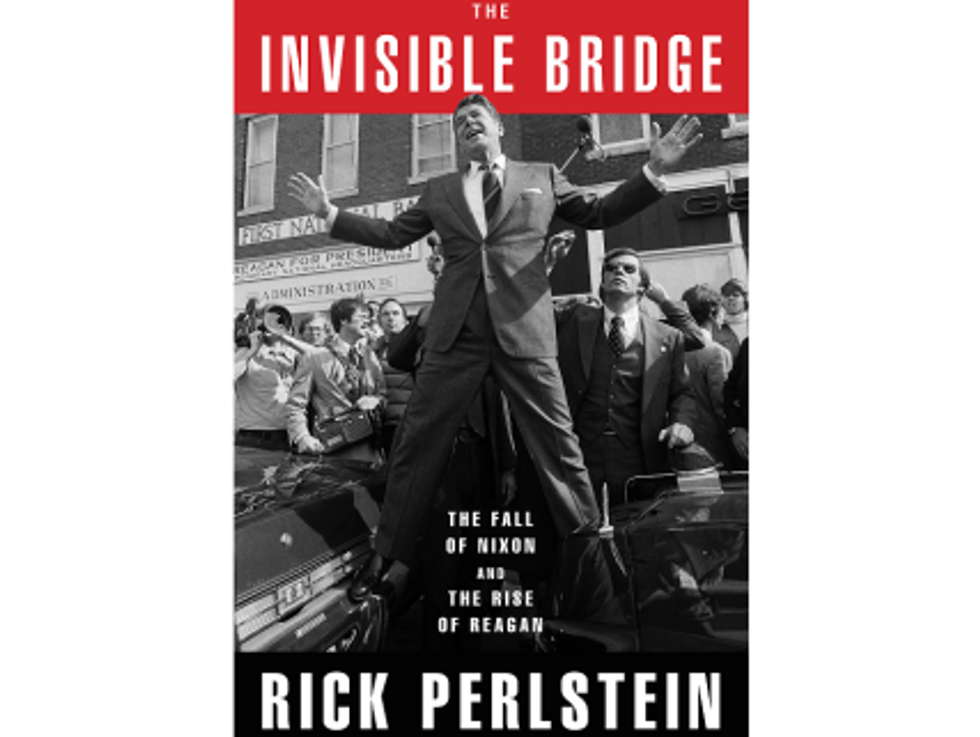

Book Review: ‘The Invisible Bridge’

The Invisible Bridge is the third and weightiest installment in Rick Perlstein’s history of postwar American conservatism. The first volume, Before the Storm (2001), culminates in Barry Goldwater’s unsuccessful presidential bid in 1964, and Nixonland (2008) carries the story through Richard Nixon’s landslide reelection in 1972. The Invisible Bridge, which comes in at 810 pages without notes, climaxes with Gerald Ford’s victory over Ronald Reagan at the 1976 GOP convention.

A self-described “European-style Social Democrat,” Perlstein is an independent scholar whose work has appeared in The Nation, Mother Jones, The Village Voice, The New Republic, and other left-of-center outlets. He also served as a senior fellow at the Campaign for America’s Future, where he blogged about conservative governance. It’s no surprise, then, that liberals are the implied audience for his history of American conservatism. He’s especially concerned to highlight the obtuseness of contemporary (mostly liberal) pundits who wrote off the conservative movement and its heroes in the aftermath of Goldwater’s waxing in 1964. Perlstein couples that critique with deep respect for the conservative movement’s passion, strategy, and execution. Its members “were taking risks for what they believed in,” he told C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb in 2001. “We could use a little more of that these days.”

Like its predecessors, The Invisible Bridge focuses on electoral politics but serves up an enormous amount of period detail, much of it culled from archives and media accounts. In Nixonland, such detail often supports the book’s main conceit: that the club Nixon organized at Whittier College prefigured his rise to national power. The Orthogonians, Perlstein noted, appealed to the unheralded college athletes who “labor[ed] quietly, sometimes resentfully, in the quarterback’s shadow.” Building on that base of low-status strivers, Nixon managed to defeat a member of the coolest campus club in the race for student body president. Nixon’s strategy hinged on the fact that workhorses far outnumber show horses in the voting population, and it eventually informed his campaigns against Helen Gahagan Douglas and John F. Kennedy.

The Invisible Bridge’s organizing device isn’t a neat parable, but a more abstract tension between American optimism and pessimism in the wake of Vietnam, Watergate, and revelations about CIA and FBI abuses. Perlstein shows that Ronald Reagan resolved that tension for many Americans by insisting that even our gravest mistakes, crimes, and sins were trivial compared to our divinely ordained role as a global leader. The problem with our Vietnam policy, Reagan maintained, wasn’t its lethal wrongheadedness but rather our halfhearted effort. He minimized Watergate in his public remarks and stood by Nixon until the end, despite political advice to the contrary. Almost by definition, America could do no wrong. If a person thought that about himself, we would regard him as a sociopath.

Forty years later, American exceptionalism still resonates in both major parties, but only one seems willing to argue, as Senator Marco Rubio did last year, that America is “the greatest country in the world, and we have nothing to apologize for.” Contrast that statement, which Perlstein describes as hubristic, with President Obama’s recent concession that in the aftermath of 9/11, “We tortured some folks. We did some things that were contrary to our values.” Obama was channeling Jimmy Carter, except that Carter couldn’t prosecute Nixon, whom Ford had pardoned before any criminal investigation. Perlstein’s stated goal in The Invisible Bridge is to resuscitate that earlier period’s debate over compromised ideals in a nation that “has ever so adored its own innocence, and so dearly wishes to see itself as an exception to history.”

As President Obama’s admission suggests, Perlstein’s formulation touches on a core issue for American liberals today. Philosopher Richard Rorty raised eyebrows in 1997 when he argued that national pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary condition for self-improvement. For a liberal pragmatist like Rorty, we raise questions about our individual or national identity not to determine who we really are or what history really means, but rather to decide what to do next or what we will try to become. For earlier generations of American liberals, Rorty wrote, “disgust with American hypocrisy and self-deception was pointless unless accompanied by an effort to give America reason to be proud of itself in the future.” After Vietnam, he claimed, the American left lost its ability to harness national pride to create a better future.

The Invisible Bridge is perhaps the most detailed account of that loss. Even as the GOP struggled to overcome Nixon’s legacy, the Democrats foundered. Jimmy Carter campaigned on creating a government “as idealistic, as decent, as competent, as compassionate, as good as its people.” Although that was enough to win in 1976, more Americans were warming to Reagan’s blithe optimism. The Invisible Bridge culminates with Reagan’s near miss at the GOP convention in 1976, but Perlstein shows that even there, Reagan was winning hearts and minds.

Perlstein’s achievement, both in this volume and the series as a whole, is impressive. The research is prodigious, the prose vivid, and one can only imagine what his treatment of Reagan’s presidency will bring. Nevertheless, the sheer quantity of detail occasionally stalls the narrative, and the enormous cast of characters, most of whom appear only once, thwarts a more thorough consideration of the major players. Many California writers (most notably Carey McWilliams and Joan Didion) nailed Perlstein’s chief protagonists in real time but receive little or no mention. Likewise, the postwar California culture that shaped Nixon and Reagan (along with Jerry Brown, who figures in the 1976 race) is passed over lightly in this third volume. Hippies, whom Governor Reagan frequently disparaged, do not appear. Aside from the The Village Voice, the alternative press is largely invisible, the environmental movement is mentioned only briefly, and Nixon’s war on drugs (which President Reagan would militarize) goes unremarked. Selection and emphasis are the author’s prerogative, and Perlstein covers a great deal of ground masterfully. Even so, his account is occasionally exhausting but not quite exhaustive, especially if the goal is to deepen our understanding of Nixon and Reagan.

The omissions inflect Reagan’s portrait in particular. Perlstein is quite right to emphasize Reagan’s uncanny ability to stage himself, but he consistently presents Reagan as a blithe if somewhat detached spirit. As Joan Didion pointed out during his presidency, Reagan’s public optimism (and daily habits) perfectly reflected the Hollywood studio system at its peak. But that system also taught him how to get ahead. Director John Huston said Reagan had “a low order of intelligence. With a certain cunning.” Perhaps the latter trait helped Reagan acquire the support of powerful if shady figures. One was his agent, Lew Wasserman, who became the king of Hollywood. Wasserman’s best friend of 50 years was Sidney Korshak, whom Perlstein describes as “the colorful attorney of Chicago’s organized crime syndicate” before dropping him from his narrative. Another Reagan patron was J. Edgar Hoover, who, we now know, leaked FBI intelligence to help the California governor smite his enemies and protect his reputation. Perlstein cites Seth Rosenfeld, whose tireless legal campaign wrested away the proof of that working partnership from the FBI, but Perlstein never explores the Hoover-Reagan connection.

These relationships complicate the conventional picture of Reagan’s sunny mythmaking without detracting from Perlstein’s achievement, which is to document the conservative movement’s extraordinary rise. His account challenges the liberal assumption that Nixon and Reagan somehow put one over on American voters. Carey McWilliams, who hammered away at Nixon from his perch at The Nation, later realized it was he who had missed the point. “Again and again I asked myself why it was that so many Americans either found it difficult to take Nixon’s measure or were prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt,” McWilliams recalled in his memoir. But Nixon hadn’t fooled anyone. Rather, McWilliams concluded, “A section of the public apparently felt that the times called for a bastard and that Nixon met the specification.” Some version of that conclusion applies to Reagan as well, and Perlstein’s epic forces American liberals to contend with that unsettling insight.

Peter Richardson is the book review editor at The National Memo. His history of Ramparts magazine, A Bomb in Every Issue, was an Editors’ Choice at The New York Times and a Top Book of 2009 at Mother Jones. In 2013, he received the National Entertainment Journalism Award for Online Criticism. No Simple Highway, his cultural history of the Grateful Dead, is scheduled for January 2015.