Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s proposal for suspending immigration from parts of the world with a history of terrorism could have a legal basis, but his assertion that it be part of a broader ban on Muslim immigrants makes it constitutionally untenable, legal scholars say.

The new twist in Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric came in the aftermath of a weekend shooting massacre at a Florida nightclub by the American-born son of Afghan immigrants.

In a fiery speech on Monday, he expanded on his proposed temporary ban on Muslims entering the United States, vowing if elected to halt immigration from any area of the world where there is a “proven history of terrorism” against America or its allies.

He also accused the Muslim-American community of broad complicity in attacks such as the Orlando shooting, which was carried out by a gunman pledging allegiance to Islamic State, and threatened “big consequences” for those who fail to inform on their neighbors.

Many legal experts said Trump’s proposal for a religion-based ban would be unlikely to pass the test of U.S. constitutional guarantees of religious freedom, due process and equal protection and would likely be struck down by the courts if he tried to implement them by presidential decree.

However, a ban on immigrants from certain countries has some precedent and might pass muster.

Some see that new proposal as reminiscent of the congressional Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was used for years to halt the influx of Chinese laborers and has been widely considered a black mark on America’s immigration record.

But Trump’s overall immigration plan would go beyond that, targeting not just a country or a region of the world but also a religion, something that no modern U.S. president has done.

“This is an absurd proposal to build a Fortress America and pull up the drawbridges,” said John Bellinger, former legal adviser to the Bush administration.

President Barack Obama took a veiled swipe at Trump on Tuesday, saying such ideas represented a “dangerous” mindset.

But U.S. presidents have wide latitude on immigration matters, and some conservative scholars said that the fate of any proposed ban would hinge on how narrowly Trump framed it.

They note, for instance, that Democratic President Jimmy Carter barred Iranian nationals from entering the United States during the 1979 Iran hostage crisis.

“If a Trump administration cut off immigration from certain countries, rather than certain religions, it would not violate the Constitution,” said John Yoo, a law professor at the University of California Berkeley and former Justice Department official who advised the George W. Bush administration on interrogation methods used on terrorism suspects.

Herman Schwartz, a law professor at American University in Washington, said if Trump stuck to his proposal for a temporary prohibition on Muslim immigrants, that raises significant constitutional questions and “shows his shaky command of the legal facts.”

MUSLIM BAN

In Monday’s speech in New Hampshire, Trump showed little sign of scaling back his call to ban Muslims from entering the United States, which he first laid out in December after an Islamic State-linked deadly mass shooting in San Bernardino, California.

Debate over the legality of Trump’s proposals was complicated by the vagueness of his pronouncement and questions on how broadly he would extend any immigration ban if elected.

While legal experts say presidents have the power to ban immigrants from specific countries, the United States does not currently ban immigration from any country. Officials do give extra scrutiny to people entering from countries such Syria and Iran.

Under the broadest interpretation of Trump’s pronouncement, immigration could be barred not only from the Muslim world but from U.S.-allied countries in Europe and Asia where militant attacks have taken place. This could include India, the source of many skilled engineers for the U.S. technology sector.

Critics say this would be impractical and counterproductive.

“Is Mr. Trump proposing to stop issuing visas even for business or tourism or education to nationals of certain countries?” said Bellinger. “Rather than increase economic growth, Mr. Trump’s plan could cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars.”

Republican Senator Jeff Sessions, a Trump foreign policy adviser, justified the candidate’s pronouncement, saying “it is perfectly appropriate for the country to refuse admission to those whose presence may be detrimental to the national interest.“

But Orrin Hatch, the longest-serving Republican in the Senate, when asked whether a president has the authority to ban immigrants based on religion, said: “I’m not sure he does.”

Legal experts also raised doubts about the legality of Trump’s demand that members of the American Muslim community “cooperate with law enforcement and turn in the people who they know are bad” or else they will be “brought to justice” themselves.” Critics have accused him of anti-Muslim fear-mongering to win votes.

“Generally, the idea that knowledge in and of itself comes with criminal liability is antithetical to the way we talk about criminal law in the United States,” said Daniel Richman, a Columbia University law professor and former federal prosecutor.

If Trump tried to implement such prosecutions as president, he said, potential defendants could simply invoke their constitutional right against self-incrimination and continue to remain silent.

(Additional reporting by Patricia Zengerle, Joan Biskupic and Lawrence Hurley; editing by Stuart Grudgings)

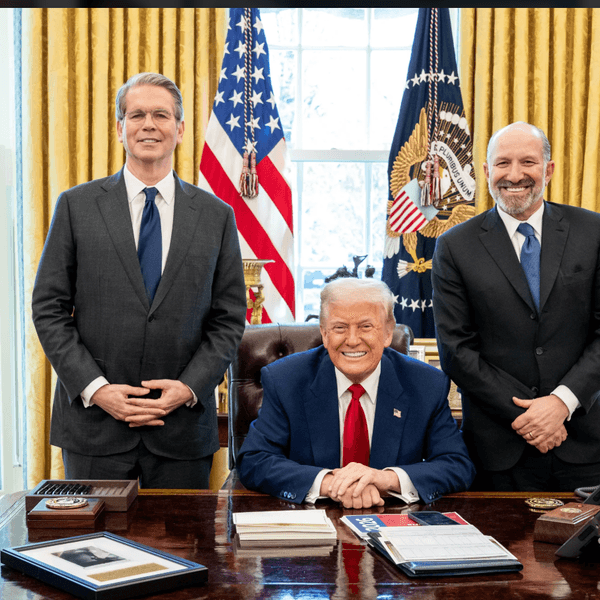

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks at a campaign rally in Greensboro, North Carolina on June 14, 2016. REUTERS/Jonathan Drake