Consumer Confidential: StubHub Has A Confused Response To Its Confusing Web Page

By David Lazarus, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

When businesses screw up, they too often duck responsibility and tell customers to pound sand. Think of United Airlines recently saying it wouldn’t honor thousands of trans-Atlantic tickets mistakenly sold for as little as $75.

When consumers mess up, however, many businesses don’t hesitate to say that customers are responsible for any and all mistaken transactions, no matter how obvious it may be that an error occurred.

Rob Robinson’s experience with the online ticket seller StubHub shows how hard it can be to get a company to listen to reason.

Robinson’s wife, Linda, went on StubHub last week to purchase three tickets to a performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic at Disney Hall.

She spent $299.69 for what she thought would be good seats. It wasn’t until she subsequently printed the tickets that she discovered she had bought $299.69 worth of parking spaces, not concert tickets.

“It’s actually an easy mistake to make,” her husband told me.

He’s right. I went to StubHub and ran a search for LA Philharmonic tickets. Two listings came up for March 12, one for the concert and one clearly marked “parking passes only.” They were right next to each other.

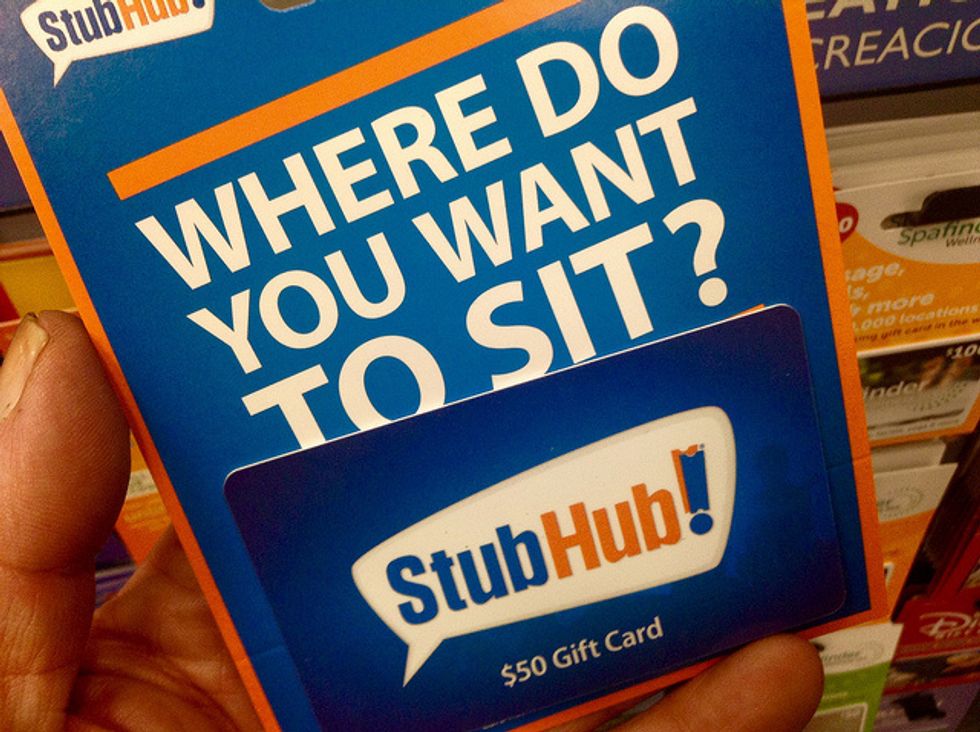

Trouble is, if you accidentally click on that second listing, you go to a page that asks, “Where do you want to sit?” And if you click the link below the available prices, you go to another page that lists “section” and “seats.”

So even though you’re buying parking spaces, StubHub’s surprisingly confusing design indicates to casual observers that seats to an event are being purchased.

Unlike Ticketmaster, which directly sells tickets to events, StubHub describes itself as a resale marketplace where people “can buy or sell tickets without restrictions or limitations.”

The website prides itself on its customer safeguards. StubHub’s FanProtect policy guarantees that you’ll receive a credit or refund if there’s a problem with your tickets or an event is canceled.

Yet when Robinson, 69, contacted StubHub to explain his situation and request a refund, he was given the brush-off.

“They told me they wouldn’t give us a refund or credit for another performance,” he said. “The best they could offer was for us to relist the parking spaces on their site and hope someone else would buy them.”

Robinson drove from his home to StubHub’s local office in downtown LA.

He once again explained what happened and pointed out how easy it is to mistakenly purchase parking spaces instead of concert tickets. Once again, StubHub’s service reps refused to budge.

This time, though, they added that they couldn’t do anything even if they wanted, Robinson said. The parking spaces, they noted, were sold through a website called Parking Panda, which is kind of like a StubHub for parking.

Mark McTamney, Parking Panda’s director of marketing, told me that the most likely scenario is that a scalper went on to his company’s site and purchased a bunch of downtown parking spaces for events at Disney Hall. The scalper then listed the spaces on StubHub to accompany concert tickets, he said.

“It had nothing to do with us,” McTamney said.

StubHub and Parking Panda are both right: This was the Robinsons’ problem, not the companies’. What’s noteworthy is the way each business responded to the situation.

Parking Panda, to its credit, didn’t hesitate to tell me that it would be open to refunding the Robinsons, though the fact that a reporter was calling might have had something to do with the company’s stand-up attitude.

StubHub demonstrated its knee-jerk inflexibility by blowing off Robinson not once but twice, on the phone and in person.

It wasn’t until Cameron Papp, a spokesman for the San Francisco company, got on the phone with me that a newfound benevolence entered the picture.

“Clearly these people tried to purchase tickets to the show, not parking,” he said. As a result, he said, StubHub will refund their money from its own pocket.

“We take these things on a case-by-case basis,” Papp explained. “We just need to make sure that the buyer is telling the truth and not trying to take advantage of us.”

That’s laudable, even though none of the service reps Robinson spoke with said anything about investigating things and offering refunds on a case-by-case basis.

I asked Papp to join me in retracing the Robinsons’ steps on StubHub’s site. I showed how even when you’ve clicked on a link to parking spaces, you’re seeing language suggesting that seats are being purchased.

“I can see how someone could get mixed up,” Papp acknowledged.

So StubHub will be fixing its site?

“No, we have no plans to make any changes,” Papp replied. “I would tell people to just pay attention to what you’re looking at.”

And I’d tell people to think twice about buying tickets from any website that doesn’t care enough about its customers to ensure the safest possible shopping experience.

Clearly it’s important that consumers be responsible for their actions. I told Robinson from the get-go that since this was his wife’s screw-up, he should be prepared to eat those $300 worth of parking spaces.

But that doesn’t let StubHub off the hook. If a site has a glitch that makes it look as if customers are buying one thing when they’re actually buying another, that would seem to give the benefit of the doubt in all cases to customers.

And if the company’s policy is to look at problems on a case-by-case basis, it should prominently tell people that _ and then act accordingly.

ABOUT THE WRITER

David Lazarus, a Los Angeles Times columnist, writes on consumer issues. He can be reached at david.lazarus@latimes.com.

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Photo: Mike Mozart via flickr