Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

The shoreline communities of Ocean County, New Jersey, are a summertime getaway for throngs of urbanites, lined with vacation homes and ice cream parlors. Not exactly pastoral — which is odd, considering dozens of Paycheck Protection Program loans to supposed farms that flowed into the beach towns last year.

As the first round of the federal government's relief program for small businesses wound down last summer, "Ritter Wheat Club" and "Deely Nuts," ostensibly a wheat farm and a tree nut farm, each got $20,833, the maximum amount available for sole proprietorships. "Tomato Cramber," up the coast in Brielle, got $12,739, while "Seaweed Bleiman" in Manahawkin got $19,957.

None of these entities exist in New Jersey's business records, and the owners of the homes at which they are purportedly located expressed surprise when contacted by ProPublica. One entity categorized as a cattle ranch, "Beefy King," was registered in PPP records to the home address of Joe Mancini, the mayor of Long Beach Township.

"There's no farming here: We're a sandbar, for Christ's sake," said Mancini, reached by telephone. Mancini said that he had no cows at his home, just three dogs.

All of these loans to nonexistent businesses came through Kabbage, an online lending platform that processed nearly 300,000 PPP loans before the first round of funds ran out in August 2020, second only to Bank of America. In total, ProPublica found 378 small loans totaling $7 million to fake business entities, all of which were structured as single-person operations and received close to the largest loan for which such micro-businesses were eligible. The overwhelming majority of them are categorized as farms, even in the unlikeliest of locales, from potato fields in Palm Beach to orange groves in Minnesota.

The Kabbage pattern is only one slice of a sprawling fraud problem that has suffused the Paycheck Protection Program from its creation in March 2020 as an attempt to keep small businesses on life support while they were forced to shut down. With speed as its strongest imperative, the effort run by the federal Small Business Administration initially lacked even the most basic safeguards to prevent opportunists from submitting fabricated documentation, government watchdogs have said.

While that may have allowed millions of businesses to keep their doors open, it has also required a massive cleanup operation on the backend. The SBA's inspector general estimated in January that the agency approved loans for 55,000 potentially ineligible businesses, and that 43,000 obtained more money than their reported payrolls would justify. The Department of Justice, relying on special agents from across the government to investigate, has brought charges against hundreds of individualsaccused of gaming pandemic response programs.

Drawn by generous fees for each loan processed, Kabbage was among a band of online lenders that joined enthusiastically in originating loans through their automated platforms. That helped millions of borrowers who'd been turned down by traditional banks, but it also created more opportunities for cheating. ProPublica examined SBA loans processed by several of the most prolific online lenders and found that Kabbage appears to have originated the most loans to businesses that don't appear to exist and the only concentration of loans to phantom farms.

In some cases, these problems would've been easy to spot with just a little more upfront diligence — which the program's structure did not encourage.

"Pushing this through financial institutions created some pretty bad incentives," said Naftali Harris, the CEO of Sentilink, which helps lenders detect potential identity theft. "This is definitely a case where companies that decided they wanted to be more careful in terms of giving out loans were penalized for doing so."

Presented with ProPublica's findings, SBA inspector general spokeswoman Farrah Saint-Surin said that her office had hundreds of investigations underway, but that she did "not have any information to share or available for public reporting at this time." Reuters reported that federal investigators were probing whether Kabbage and other fintech lenders miscalculated PPP loan amounts, and the DOJ declined to confirm or deny the existence of any investigation to ProPublica.

Kabbage, which was acquired by American Express last fall, did not have an explanation for ProPublica's specific findings, but it said it adhered to required fraud protocols. "At any point in the loan process, if fraudulent activity was suspected or confirmed, it was reported to FinCEN, the SBA's Office of the Inspector General and other federal investigators, with Kabbage providing its full cooperation," spokesman Paul Bernardini said in an emailed statement.

As soon as the pandemic swept across America, Kabbage was in trouble.

The online lending platform had launched in 2009 as part of a generation of financial technology companies known as "non-banks," "alternative lenders" or simply "fintechs" that act as an intermediary between investors and small businesses that might not have relationships with traditional banks. Based in Atlanta, it had become a buzzy standout in the city's tech scene, offering employees Silicon Valley perks like free catered lunches and beer on tap. It advertised its mission as helping small businesses "acquire funds they need for their big breaks," as a recruiting video parody of Michael Jackson's "Thriller" put it in 2016.

The basic innovation behind the burgeoning fintech industry is automating underwriting and incorporating more data sources into risk evaluation, using statistical models to determine whether an applicant will repay a loan. That lower barrier to credit comes with a price: Kabbage would lend to borrowers with thin or checkered credit histories, in exchange for steep fees. The original partner for most of its loans, Celtic Bank, is based in Utah, which has no cap on interest rate, allowing Kabbage to charge more in states with stricter regulations.

With backing from the powerhouse venture capital firm SoftBank, Kabbage had been planning an IPO. Its model foundered, however, when Kabbage's largest customer base — small businesses like coffee shops, hair salons and yoga studios — was forced to shut down last March. Kabbage stopped writing loans, even for businesses that weren't harmed by the pandemic. Days later, it furloughed more than half of its nearly 600-person staff and faced an uncertain future.

The Paycheck Protection Program, which was signed into law as part of the CARES Act on March 27, 2020, with an initial $349 billion in funding, was a lifeline not just to small businesses, but fintechs as well. Lenders would get a fee of 5% on loans worth less than $350,000, which would account for the vast majority of transactions. The loans were government guaranteed, and processors bore almost no liability, as long as they made sure that applications were complete.

At first, encouraged by the Treasury Department, traditional banks prioritized their own customers — an efficient way to process applications with little fraud risk, since the borrowers' information was already on file. But that left millions of the smallest businesses, including independent contractors, out to dry. They turned instead to a collection of online lenders that have sprung up offering short-term loans to businesses: Kabbage, Lendio, Bluevine, FundBox, Square Capital and others would process applications automatically, with little human review required.

For the platforms, this was also easy money. In the first funding round that ran out last August, Kabbage completed 297,587 loans totaling $7 billion. It received 5% of each loan it made directly and an undisclosed cut of the proceeds for those it processed for banks; its total revenue was likely in the hundreds of millions of dollars. A lawsuit filed by a South Carolina accounting firm alleges that Kabbage was among several lenders that refused to pay fees to agents who helped put together applications, even though the CARES Act had said they could charge up to 1% of the smaller loans (a provision that was later reversed). For Kabbage, that revenue kept the company alive while it sought a buyer.

"For all of these guys, it was like shooting fish in a barrel. If you could do the minimum amount of due diligence required, you could fill up the pipeline with these applications," said a former Kabbage executive, one of four former employees interviewed by ProPublica. They spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid retaliation at their current jobs or from industry giant American Express.

To handle the volume, Kabbage brought back laid-off workers starting at $15 an hour. When that failed to attract enough people, they increased the hourly rate to $35, and then $40, and awarded gift cards for reaching certain benchmarks, according to a former employee with visibility into the loan processing. "At a certain point, they were like, 'Yes, get more applications out and you'll get this reward if you do,'" the former employee said. (Bernardini said the company did not offer incentive compensation.)

In a report on its PPP participation through last August, Kabbage boasted that 75% of all approved applications were processed without human review. For every 790 employees at major U.S. banks, the report said, Kabbage had one. That's in part because traditional banks, which also take deposits, are much more heavily regulated than fintech institutions that just process loans. To participate in the PPP, fintechs had to quickly set up systems that could comply with anti-money laundering laws. The human review that did happen, according to two people involved in it, was perfunctory.

"They weren't saying, 'Is this legitimate?' They were just saying, 'Are all the fields filled out?'" said another former employee. As acquisition talks proceeded, the employee noted, Kabbage managers who held the most company stock had a built-in incentive to process as many loans as possible. "If there's anything suspicious, you can pass it along to account review, but account review was full of people who stood to make a lot of money from the acquisition."

One situation in which Kabbage approved a suspicious loan became public in a Florida lawsuit filed by a woman, Latoya Clark, who received more than $1 million in PPP loans to three businesses. When the funds were deposited into accounts at JPMorgan Chase, the bank discovered that Clark's businesses hadn't been incorporated before the PPP program's cutoff and froze the accounts. Clark sued Chase, and Chase then filed a counterclaim against the borrower and Kabbage, which had originated the loan despite its questionable documentation. In its response, Kabbage said it had not yet completed its investigation of the incident.

Although the Justice Department rarely names lenders that processed fraudulent PPP applications, Kabbage has been named at least twice. One case involved two loans worth $1.8 million to businesses that submitted forged information, and the otherinvolved a business that had inflated its payroll numbers and submitted a similar application to U.S. Bank, which flagged authorities. Kabbage had simply approved the $940,000 loan. American Express' Bernardini declined to comment further on pending litigation.

Shortly after the application period for PPP's first round closed on Aug. 8, American Express announced the Kabbage purchase. But the transaction included none of Kabbage's loan portfolios, either from the PPP or its pre-pandemic conventional loans. The PPP loans had either been sold to SBA-approved banks or bought by the Federal Reserve. Bernardini wouldn't say which banks now own the loans, however, and said that no potentially fraudulent loans had been pledged to the Fed.

In April, an Ocean County, New Jersey, resident contacted ProPublica after seeing his name attached to a Kabbage loan for a nonexistent "melon farm." To see whether it was an isolated incident, ProPublica took basic information the government released after a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by ProPublica and others and compared it with state business entity registries. Although registries don't pick up all sole proprietorships and independent contractors, the absence of a name is an indication that the business might not exist.

As it turned out, Kabbage had made more than 60 loans in New Jersey to unlisted businesses. Fake farms also showed up repeatedly in the SBA's Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program, according to reports from local news outlets.

A common tie became apparent when the resident of the home to which one nonexistent business was registered said that he was a client of the certified public accountants at Ciccone, Koseff & Company. In March 2020, the firm notified its clients of what it called an "ultimately unsuccessful ransomware attack" that occurred the previous month. According to information filed with Maine's attorney general, the attackers acquired Social Security numbers and financial information.

Several other clients of the accounting firm, including Mancini, the Long Beach mayor, also had loans registered to their addresses. Reached by phone, firm founder Ray Ciccone declined to comment.

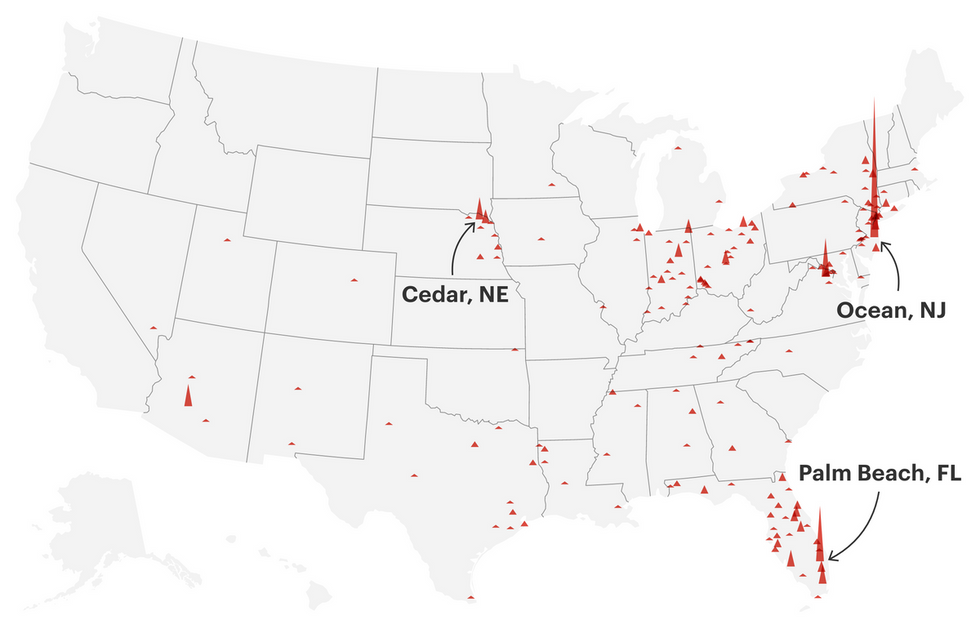

But that CPA's data breach didn't account for all of the suspicious loans ProPublica found across the country. Searches for PPP applicants that didn't show up in state registration records yielded hundreds in 28 more states, with dense clusters in Florida, Nebraska and Virginia. Other lenders had nonexistent businesses as well, but fake farms only showed up in Kabbage loans. Most followed a distinctive naming convention, with part of the name of a resident or former resident of the home to which the business is registered, plus a random agricultural term.

PPP loan applications approved by Kabbage, an online lender, to recipients who appear not to exist or say they did not apply, by county.

Source: Small Business Administration Credit: Derek Willis/ProPublica

Some of the fake loans listed addresses of people who'd also legitimately applied for their businesses. Hartington, Nebraska, anesthesiologist Bruce Reifenrath received a PPP loan for his practice in nearby Yankton, South Dakota. That's why the idea of one being approved for a "potato farm" was so strange. "We did a PPP loan last spring and it's pretty extensive, the documentation," Reifenrath said.

Reifenrath was part of a cluster of dubious Kabbage loans in Hartington that also included the home of J. Scott Schrempp, the president of the Bank of Hartington, who confirmed that he did not own a strawberry farm. Schrempp said he had noticed the fake loan, and reported it to the SBA.

The SBA data only reflects approved applications received from lenders, some of which are then caught and not funded. The SBA also periodically updates its dataset to remove loans canceled by lenders. But none of the suspicious loans pulled by ProPublica show undisbursed funds, and they all have remained in the dataset for more than eight months.

One possible mechanism for the invented businesses is a technique known as synthetic identity theft, in which a criminal obtains pieces of personally identifiable information — such as a home address, a Social Security number and a birthdate — and combines it with fake information to build a credit profile. The associated bank account then routes to the fraudster, not the owner of the original information.

None of the residents of the phony farms ProPublica contacted were getting notices that they needed to repay the loans they didn't apply for, because they didn't get any money. But that doesn't mean they're not at risk, according to James Lee, chief operating officer at the Identity Theft Resource Center.

"Just having an address linked to your name on a fraudulent loan can impact your credit," Lee said. It can also pose problems for pre-employment background checks, insurance applications or new identification documents like passports and driver's licenses.

Meanwhile, if not corrected, the fabricated identities will stay in circulation and become better at fooling other financial institutions. "Those records get built into the credit and authentication systems used by government and commercial entities," Lee said. "Each next time they are used and authenticated, the more 'real' they become. That's what makes synthetic identity fraud so insidious."

This, however, is largely not Kabbage's problem anymore.

After its huge blitz of PPP loans last summer, Kabbage had hundreds of thousands of borrowers whose loans would need to be serviced until they were closed out. The loans could either be forgiven, if the borrower demonstrated that they spent most of the money on payroll, or paid back with interest. But American Express didn't acquire the part of Kabbage's business that owned those loans. Instead, a separate entity called K Servicing would handle loan forgiveness and take applications for a second PPP draw that Congress funded in December. The servicer is led by former Kabbage employees and its website looks very similar to Kabbage's, but American Express says it has no affiliation.

If Kabbage was understaffed for the volume of PPP loans it took on before the acquisition, the situation has apparently worsened since then. Reddit, Yelp, Consumer Affairs, Trustpilot, Facebook and Better Business Bureau threads are replete with complaints from customers whose applications were denied or who received no communication from the company. When the SBA changed the rules in February to make the program more generous to independent contractors, K Servicing couldn't incorporate the new forms into its processing system. So it told all new applicants to apply through another company, SmartBiz, which had operated as a mostly online processor of SBA loans even before the pandemic.

K Servicing is run by Kabbage's former head of program management, Laquisha Milner, who also runs her own consulting firm. "Due to extenuating circumstances beyond our control, currently, our processing function is delayed," Milner emailed in response to detailed questions from ProPublica. "We are relentlessly exploring all available options to ensure our existing customers are able to maximize their loan forgiveness."

Jennifer Dienst is a freelance travel and events writer who received her first-draw loan from Kabbage and wants to apply for forgiveness before her window for doing so closes in the fall, but she has been stymied by K Servicing's failure to make the forms available. "Please be patient with us as we prepare for the new forms," a message on the loan portal reads.

Meanwhile, Dienst's account has started accruing interest, which Milner said will not be charged if the loan is forgiven. But it's making Dienst nervous.

"It's always the same response from K Servicing — we're updating our forgiveness forms and they'll be made available soon," Dienst said. "They've been saying that for months."

Clarification, May 18, 2021: This story has been clarified to more accurately reflect the terms of Kabbage's acquisition by American Express.