Schools Increase Awareness Of Trauma’s Impact On Learning

By Elisa Crouch, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (TNS)

JENNINGS, Mo. — The list was a familiar one to the counselors looking at the projector screen inside the Jennings high School cafeteria.

Physical abuse. Violence to mother. Abandonment. Divorce.

The school counselors nodded their heads, indicating they have high percentages of children in their schools who’ve experienced a number of these traumatic events. This kind of trauma can profoundly impact nearly every aspect of a child’s development and ability to function, Patsy Carter of the Missouri Department of Mental Health told them. It can hurt a child’s ability to control behavior, and have negative consequences on classroom learning.

It’s an approach to education that the counselors in Jennings worked on for two days last week to better understand.

“This is not a free pass,” Carter said to the counselors and district administrators sitting at three round tables. “But if we want their behavior to change we have to look at it through the lens of trauma and the impact.”

The Jennings School District is on the forefront of work to create trauma-informed schools, places where teachers move away from suspending students for disruptive behavior, and toward looking for the root cause of the actions.

In schools with this mindset, students still face consequences for lashing out at a teacher. But teachers and counselors are trained to determine the trigger points for such action, and how to help a child move himself or herself out of stress mode.

“We really are changing mindsets about how do we work with people — parents, students and teachers,” said Superintendent Tiffany Anderson, who sat through the training sessions. “We really are wrapping services around the whole child and helping them better their lives. So often systems are punitive in how they handle these issues. As educators we really can be proactive and be problem solvers to look at the root.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than half of the U.S. population has experienced at least one traumatic event during childhood. Children in high-poverty communities such as Jennings are at greater risk to experience chronic trauma.

Though many children are able to move past these experiences, others struggle throughout their life with chronic stress. That stress can lead to a long list of health problems and a shorter lifespan.

Eventually, Anderson wants every staff person in the district — from the principals to the janitors — to go through trauma training.

The district has a 30-month grant from the Missouri Foundation for Health through Washington University’s pediatric program to infuse the approach throughout the district.

“It’s more than just training,” said Sarah Garwood, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Washington U.

Trauma-sensitive schools began in Washington state, where a principal in Walla Walla found that addressing trauma is more effective than responding to behavior with punishment alone. Other districts in Missouri, including Kansas City and Independence, are integrating this approach into their schools.

For generations, the standard response to chronic disruptive behavior has been suspension, even for children in kindergarten.

In February, a study by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA found 3.5 million U.S. children lost almost 18 million days of instruction in the 2011-12 school year to suspensions. Keeping students out of school reduces their chances of graduation and success, a phenomenon commonly called the school-to-prison pipeline.

Black elementary school children are more likely to be suspended in Missouri than in any state in the nation, the report found. Missouri also has the greatest disparity between how often black and white students get out-of-school suspension for infractions.

Educators are increasingly questioning whether suspending students improves their behavior. It’s rare that an adult is working with students after they’re sent home — on homework or behavior — often leading to more misbehavior, punishment and, eventually, academic failure.

“It’s a moral imperative that we address the entire child,” Monica Barnes-Boateng, assessment and data coordinator for Jennings, said during a break. “We can’t begin to help them with student learning outcomes until you address their personal needs.”

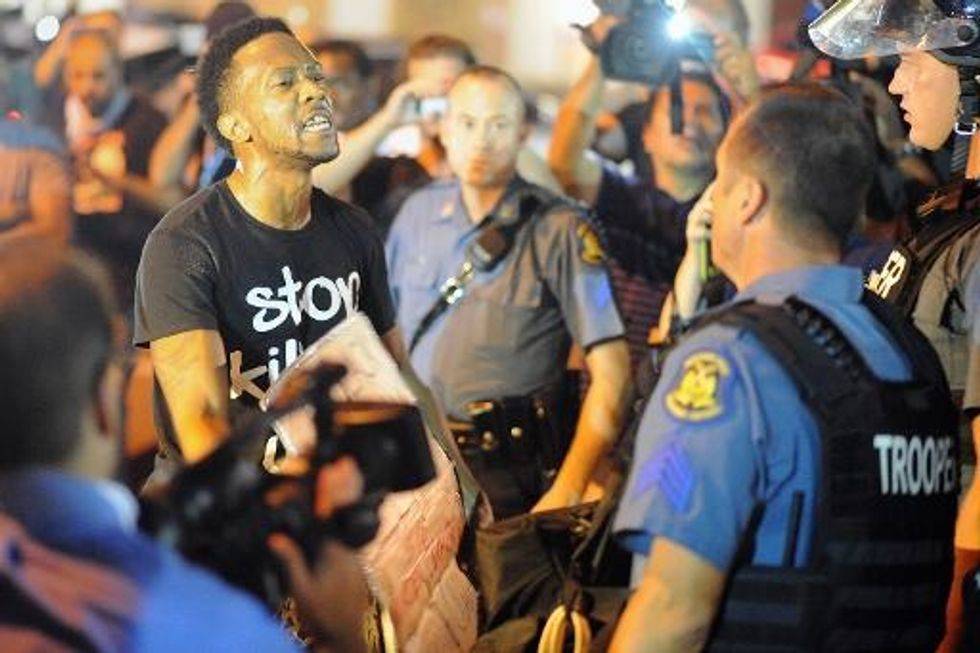

Photo: Students suffering from trauma — which can include divorce, family squabbles and the effects of poverty — often act out. Some school districts are wondering if punishment for infractions is really the best way to treat misbehaving children. Flickr/Phoney Nickle