Three Vital Questions For A Covid-19 Commission

Reprinted with permission from Deep State Blog.

Rep. Adam Schiff, chair of the House Intelligence Committee wants a bipartisan commission to investigate the government's response to the COVID19 pandemic.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks President George Bush stoutly resisted the creation of a committee to investigate of how the hijackers were able to penetrate America's defenses. Only the congressional intelligence committees should investigate, Bush said, and only behind closed doors. Vice President Cheney said those who charged the attacks on New York and Washington represented an intelligence failure were "irresponsible."

So we can expect President Trump, allies, cronies, and trolls to resist Rep. Adam's Schiff's call for 9/11 style national commission to investigate the response to COVID outbreak that emanated from China last December.

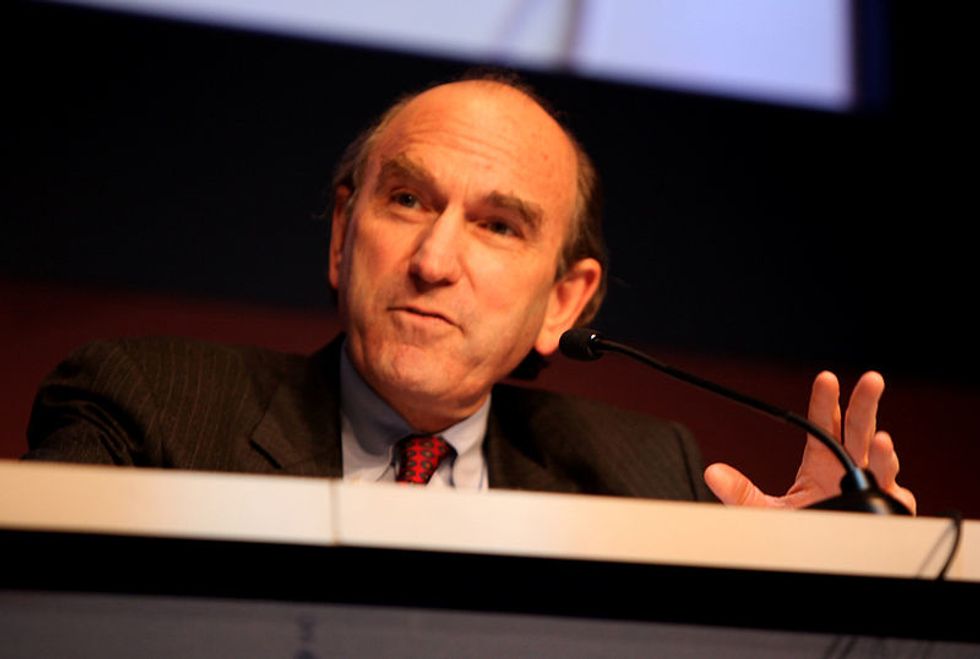

National Security Adviser

National Security AdviserJohn Bolton, Twitter addict and unemployed geopolitical provocateur, prefers the United States take punitive action toward China for Beijing's bungled response. He's not alone. The problem isn't China, says Josh Rogin of the Washington Post, it's the"Chinese Communist Party Virus."

There's no contradiction, however, between holding governments in Beijing and Washington accountable, as National Memo's Joe Conason notes.

A serious investigation of the pandemic, its origins and its almost unimpeded swath of destruction would begin by identifying the actual source of the disease and examining how the virus jumped into the human population. Such an investigation would necessarily examine the Chinese government's responsibility in having concealed the outbreak at the very beginning, when it might have been eradicated at relatively little cost.

And then the investigation would probe Washington's ruinous neglect of the pandemic threat as it loomed over this country.

The goal is not to point fingers at individuals or countries (although that may be in order) but to overhaul U.S. national defenses, to rethink our definition of national security and to reorganize our the national security state accordingly.

COVID19 investigators can start by asking three questions.

- Who set priorities at the Office of Director of National Intelligence?

Pandemic warning on p. 21.

Pandemic warning on p. 21.The ODNI was created after 9/11 precisely to create a body of intelligence analysts with a broader view of national security than any one agency. To its credit, ODNI cogently identified the danger of pandemic in its 2019 threat assessment.

We assess that the United States and the world will remain vulnerable to the next flu pandemic or large-scale outbreak of a contagious disease that could lead to massive rates of death and disability, severely affect the world economy, strain international resources, and increase calls on the United States for support. Although the international community has made tenuous improvements to global health security, these gains may be inadequate to address the challenge of what we anticipate will be more frequent outbreaks of infectious diseases because of rapid unplanned urbanization, prolonged humanitarian crises, human incursion into previously unsettled land, expansion of international travel and trade,and regional climate change.

This warning is spot on. The problem is that it came halfway through a 42-page catalogof dangers facing the United States. For ODNI, the threat of a pandemic ranked slightly behind the dangers posed by Salvadoran street gangs and war in outer space.

On a Cipher Brief group call, I asked former Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff if ODNI's buried finding represented an intelligence failure. He ducked the question saying, "There's always the issue of what the consumer [ meaning the rest of the government and the White House] wants to hear."

In other words, other agencies worried about counterterrorism and Russian influence operations, so ODNI downgraded the danger of pandemics. That sounds like an admission that the U.S. intelligence community, which prides itself on "speaking truth to power," chose not to do so in this case.

In the mental universe of ODNI, the poor gangsters of MS-13 represent a greater threat to the American people than an untreatable contagious illness. One can debate whether racism affected ODNI's judgment but one cannot dispute that its muffled warning wasn't much help to policymakers or the public.

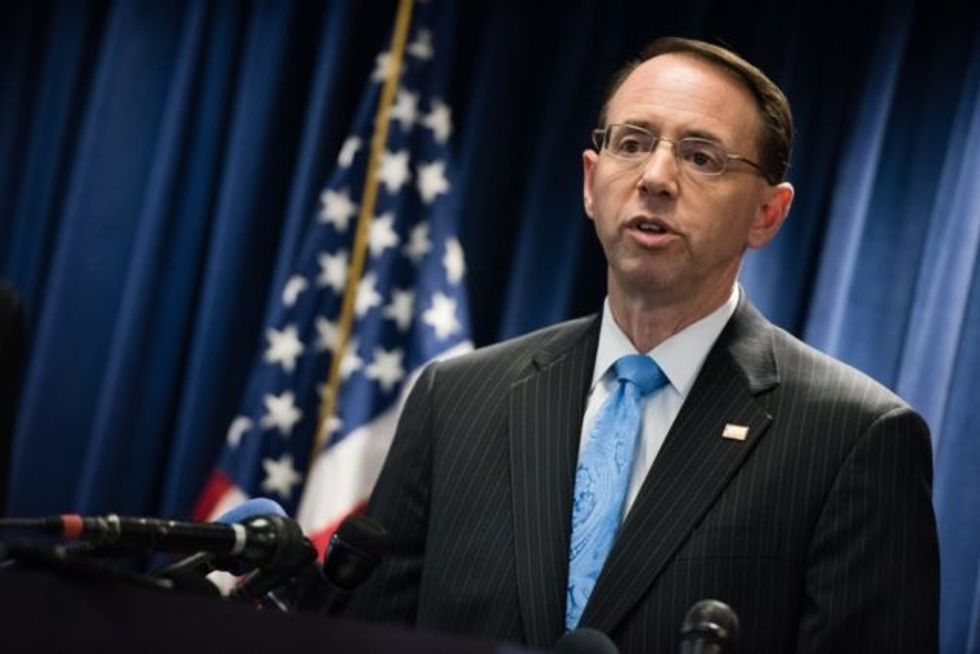

The U.S. intelligence community is disturbed because Richard Grenell, a lightly qualified former press spokesman, now serves as Acting DNI. Grenell is indeed a hack. But Grenell was not responsible for ODNI's faulty priorities. Former ODNI Dan Coats was. Coats needs to testify.

2) What did John Bolton's dismantle the NSC's pandemic office?

A second failure of intelligence occurred at the National Security Council.

In May 2018, National Security Adviser John Bolton "streamlined" the NSC's Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense right out of existence. The directorate had been created by the Obama administration after the Ebola scare of 2014, in which the deadly disease ravaged Africa. This hub for expertise and institutional memory was dispersed, as its last director wrote in the Washington Post.

Bolton saw a greater threat emanating from the besieged government of Venezuela. "Regime change" was a higher priority than "Global Health Security." Bolton's explanation for his re-organization needs to be heard, preferably under oath.

3) Why didn't the Defense Department's medical intelligence office show more leadership?

Another node of apparent failure was the National Center for Medical Intelligence (NCMI), which operates as part of the Defense Intelligence Agency. The story comes from former U.S military intelligence officer Scott Ritter, writing in The American Conservative.

The mission of the NCMI is to serve as the lead activity within the Department of Defense (DoD) "for the production of medical intelligence," and to prepare and coordinate "integrated, all-source intelligence for the DoD and other government and international organizations on foreign health threats and other medical issues."

The office had proved its value before, Ritter writes.

…[I]n April 2009—two months prior to when the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially declared the global outbreak of H1N1 influenza a pandemic, NCMI published an intelligence product, known as an "Infectious Disease Risk Assessment," which predicted that a recent outbreak of the Swine Flu (H1N1) would become a pandemic.

The coronavirus was clearly part of the NCMI's remit, he notes

And yet its first Infectious Disease Risk Assessment for COVID-19 was issued on January 5, 2020, reporting that 59 people had been taken ill in Wuhan, China. This report was derived not from any sensitive intelligence collection effort or independent biosurveillance activity, but rather from a report issued to the WHO by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, dated January 5, 2020.

Ritter doesn't point a finger at Trump. He asks, how will NCMI improve on its weak performance?

As President Trump noted on March 17, however, it would have been helpful to have had advance warning. That was the job of the NCMI, and they failed. This failure may have been a result of complacency, incompetence, or just a byproduct of circumstance. Regardless of the reason, the NCMI needs to learn from this experience, and reexamine the totality of the intelligence cycle—the direction, collection, analysis and feedback loop—associated with its failure to adequately predict the coronavirus pandemic.

And Ritter asks an epidemiological question: Did the virus originate in animals or in humans? Multiple government statements say it came from animals. But Ritter reports

that the Joint Field Epidemiology Investigation Team, a specialized task force working under the auspices of the Chinese Center for Disease Control (CCDC), found that the COVID-19 epidemic did not [emphasis added] originate by animal-to-human transmission in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, as originally believed, but rather human-to-human transmission totally unrelated to the operation of the market.

That's certainly not the conventional wisdom. So, who's right? Where did the virus come from? That's one more question that needs to be asked and answered by the coming COVID19 investigation.

Source: The Staggering Collapse of U.S. Intelligence on the Coronavirus | The American Conservative