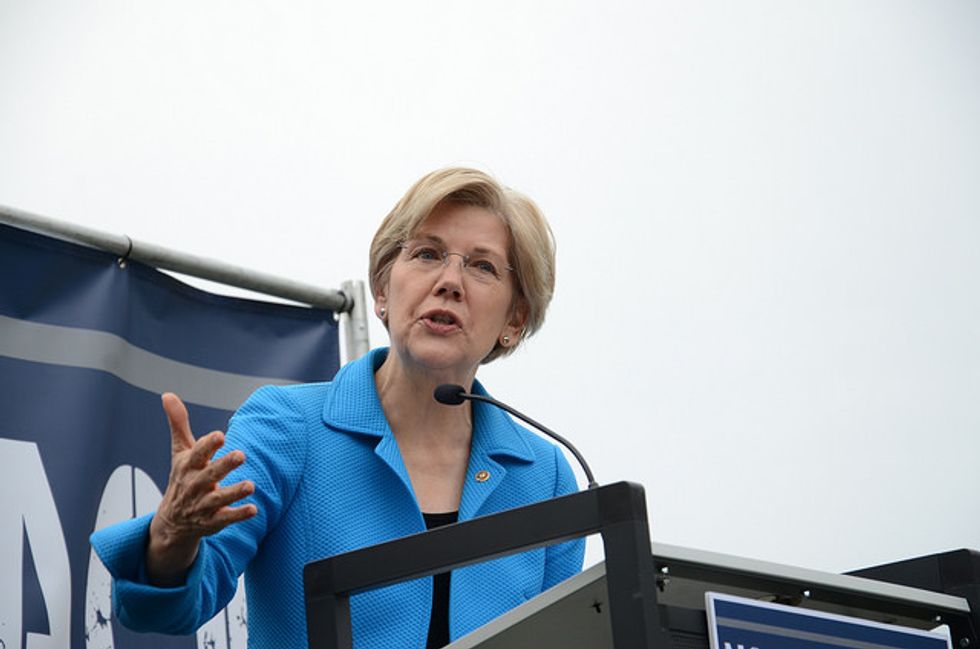

Elizabeth Warren Skipped 2016 Run, But Has Stayed In Picture

By Joshua Green, Bloomberg News (TNS)

WASHINGTON — Early last year, the frenzy to enlist Elizabeth Warren in the 2016 presidential race grew so intense that a Ready for Warren group emerged to lead a draft effort. Reporters parsed the Democratic Massachusetts senator’s every utterance for clues to her plans. In the end, Warren opted to pass. But so far, she hasn’t chosen to throw her support behind any of the other candidates.

With President Barack Obama unlikely to weigh in, Warren is the most important Democratic elected official who has yet to endorse. Her iconic status among the party’s liberal grass roots, and the national fundraising base she commands, would deliver a substantial boost to Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, or Martin O’Malley.

Sanders would appear to be the most ideologically compatible choice for Warren, because his populist, anti-Wall Street rhetoric mirrors her own. And indeed, many of her supporters, including the founders of her draft movement, have embraced him. But Warren has been noticeably reluctant to lend her name to Sanders’s presidential campaign, because, her advisers say, she’s determined that Democrats should hold on to the White House after Obama leaves office and is not convinced Sanders could win. “Her prime directive is not to damage the party’s chances in November,” says a close Warren associate, who has discussed the matter with her.

Yet, while she signed a 2013 letter urging Clinton to run, Warren is the only female Democratic senator who hasn’t backed the former secretary of state. She was also the lone senatorial no-show at the Clinton campaign’s Nov. 30 Women for Hillary rally near the Capitol. “Maybe she has a cold,” Maryland Sen. Barbara Mikulski deadpanned at the time. Representatives for Warren, Clinton, and Sanders declined to comment.

Warren isn’t being entirely silent. She periodically emerges to praise the major candidates for espousing policies she favors. In December, the Clinton campaign was elated when Warren took to Facebook to praise the candidate’s call to block riders in the year-end budget bill that would have weakened financial regulations.

“Secretary Clinton is right to fight back against Republicans trying to sneak Wall Street giveaways into the must-pass government funding bill,” Warren wrote. “Whether it’s attacking the (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau), undermining new rules to rein in unscrupulous retirement advisers, or rolling back any part of the hard-fought progress we’ve made on financial reform, she and I agree: ‘President Obama and congressional Democrats should do everything they can to stop these efforts.’”

Sanders has garnered similar approbation. On Jan. 6, Warren unleashed a tweet storm in support of his speech on Wall Street reform: “I’m glad @BernieSanders is out there fighting to hold big banks accountable, make our economy safer, & stop the GOP from rigging the system.”

Warren’s allies argue that she’s been able to shape the primary race by creating a “system of incentives” that has influenced candidate behavior. “There was almost no oxygen in the room for big, structural Wall Street reform after Dodd-Frank until Warren came on the scene,” says Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a liberal group. “The fact that all three Democratic presidential candidates are competing with each other to have the boldest plan for Wall Street reform and accountability — including explicitly calling for jailing Wall Street bankers who broke the law — is testament to Warren’s looming presence and influence in the Democratic primary.”

Warren has extracted some significant policy commitments that will be difficult for a future Democratic president to break. In August, Vice President Joe Biden met privately with Warren while considering a presidential run. A week later, Clinton endorsed a bill that Warren has championed restricting “golden parachute” pay packages for Wall Street bankers who take jobs with the federal government — a development many liberals took as a sign that Clinton feared losing Warren’s support to Biden.

Given the almost Trump-like media fixation with Warren as recently as a year ago, it’s remarkable that she’s disappeared from the presidential race to the degree that she has. While it’s possible that she will be able to maintain her low profile until a nominee emerges, it’s also easy to envision a scenario in which she is thrust right back into the race: Both Clinton and Sanders backers agree that if Sanders were to prevail in Iowa and New Hampshire, Warren would come under intense pressure from both candidates to deliver an endorsement.

©2016 Bloomberg News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: AFGE via Flickr