Analysis: Why It’s So Hard To Understand 2016 With Numbers Alone

By Ken Goldstein, Bloomberg News (TNS)

WASHINGTON — The new breed of cool analytical election observers — from Nate Silver to the folks at the Upshot or Monkey Cage — roll their eyes and sigh deeply at the frenzy of coverage about Donald Trump, the media scrum about Hillary Clinton’s emails, and the speculation about whether Joe Biden will enter the presidential race. Instead, they argue, one should simply pay attention to the fundamentals and not worry about campaigns, debates, events, or even, seemingly, the identities of the candidates.

I’m all for models based on objective and quantifiable data like the state of the economy or the likely demographics of the electorate. They force analysts and observers to be precise and transparent about their assumptions. One can disagree with those assumptions, but at least one knows exactly what those assumptions are.

The problem with that approach is, when it comes to primaries, the fundamentals are not nearly as well understood or as predictive as they are in general elections. In other words, predicting the arc and ultimate outcome of the presidential nomination process is much more difficult than analyzing general elections. Partisanship and assessments of how the incumbent party is doing are absent when one is looking at primaries.

Presidential nominations are not single-day contests with two candidates from clearly defined parties competing to get the plurality of the vote in enough states to garner 270 Electoral College votes. They are dynamic multi-month, multi-candidate contests between rivals who often differ little on the issues and compete to win delegates in states, which often have different sets of rules. They are a process in which, as scholars like Vanderbilt University’s Larry Bartels have shown, previous primary performances and expectations can influence subsequent contests. In short, while it may prove to be short-lived, momentum matters.

Furthermore, even in general elections when we can model with fairly tight precision likely outcomes, much of the analysis and most of the “modeling” tend to rely on the very same polls that more traditional observers of politics utilize. They may, like many of the more traditional observers, augment those polls with their assessments of the national environment or the quality of the candidates and their campaigns, but many of the predictions are basically based on polls.

So, what would a passion-free focus on the most recent poll numbers tell us?

Well, in one contest, according to the Pollster.com averages, there is a candidate comfortably at the top of the national polls of what is universally considered to be a strong field of 16 candidates that includes four sitting U.S. senators and four sitting governors, as well as former governors from two of out of the three largest states in the country.

This candidate enjoys a 15 percentage-point lead over the second place contestant in national polls (and together they are the only candidates with double-digit support). This candidate is leading the pre-race favorite by a margin of nearly four to one and has almost three times as much support as the four sitting senators combined. That same candidate is also leading beyond the margin of error in the crucial early nominating contests of Iowa and New Hampshire. In both national and state specific polls, the lead has grown since the start of the summer as has this candidate’s favorability ratings among potential primary voters. This candidate is well-funded and, to date, has spent no money on television advertising.

In the other contest, according to Pollster.com, the leading candidate has a similarly sized lead, 18 percentage point lead — but in a field that is considerably smaller and that includes one sitting U.S. senator (who is actually not a member of the party whose nomination he is running for) as well as three former office holders (two of whom used to be members of the other party).

Looking at Pollster.com’s aggregation, the national lead is about half of what it was at the start of the summer with a new ABC News/Washington Post poll showing a drop of 20 percentage points in support. According to the Pollster.com average, this candidate is trailing in New Hampshire and leading in Iowa (with both races within the margin of error). But a CBS News/YouGov poll this week also showed this candidate trailing in Iowa. This candidate has spent heavily on advertising in the early states with no opposition on the air.

So, what is the conventional wisdom from the cool analytical kids and the old guard of political pundits? It turns out that it is exactly the same. They both say that the first candidate has virtually no chance at the nomination and the second remains the presumptive nominee.

The first candidate is obviously Donald Trump and the second Hillary Clinton. Why does Clinton’s shrinking lead in national polls and weakness in early states make her likely to win, while Trump’s expanding lead in national polls and strength in early states give him almost no chance of being the Republican nominee? How can it be too much too early to take Trump seriously and dangerously late for Vice President Joe Biden to mount a challenge?

One thing is clear: The answers to those questions do not flow from just looking at polling numbers. Ultimately, the work of the data journalists and more traditional observers of politics include a good dose of instinct.

Endorsements have become the favorite fundamental or favorite tell for modelers. While the causality is not clear, endorsements certainly correlate with outcomes. Front-runners with large numbers of early endorsements like Walter Mondale in 1984, Bob Dole in 1996 and George W. Bush in 2000 tended to fare well.

It is certainly the case that Clinton has an overwhelming lead in the endorsements race. But something is making Joe Biden take another look. While it is clearly a deeply personal decision, some part of that decision is based on his calculation on whether or not he could win the Democratic nomination. Clearly, while estimating that precise number is difficult, it is clearly higher than it was at the beginning of the summer.

So, yes, it’s early. Clinton remains the favorite to be the Democratic nominee and has a solid chance of becoming the 45th president. But Clinton had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad summer that has shrunk her lead in the Democratic primary and wounded her reputation with general election swing voters to the point that she is running neck and neck with Donald Trump in general election match-ups. Of course, polls today are not predictive of November 2016 results, but they may end up getting her a challenge from a sitting vice president. And, if you want to look at correlations from previous nomination fights as a guide or “model,” the last four sitting vice presidents who sought their party’s presidential nomination succeeded — Al Gore in 2000, George H.W. Bush in 1988, Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and Richard Nixon in 1960.

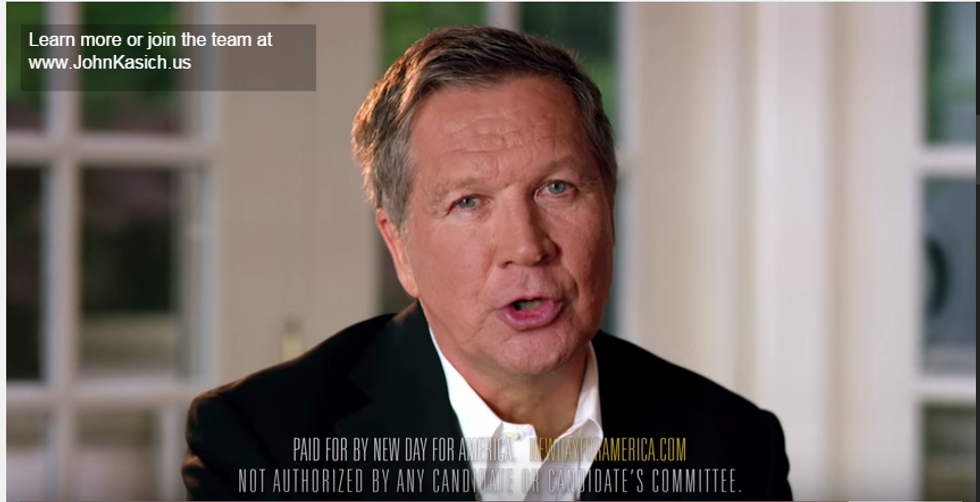

Photo: This man — Nate Silver — is not the be-all and end-all of presidential futurism. (CC) JD Lasica, Socialmedia.biz