Nixon Agonistes — His Tainted Legacy Still Overshadows The Nation

By Laura Malt Schneiderman, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (TNS)

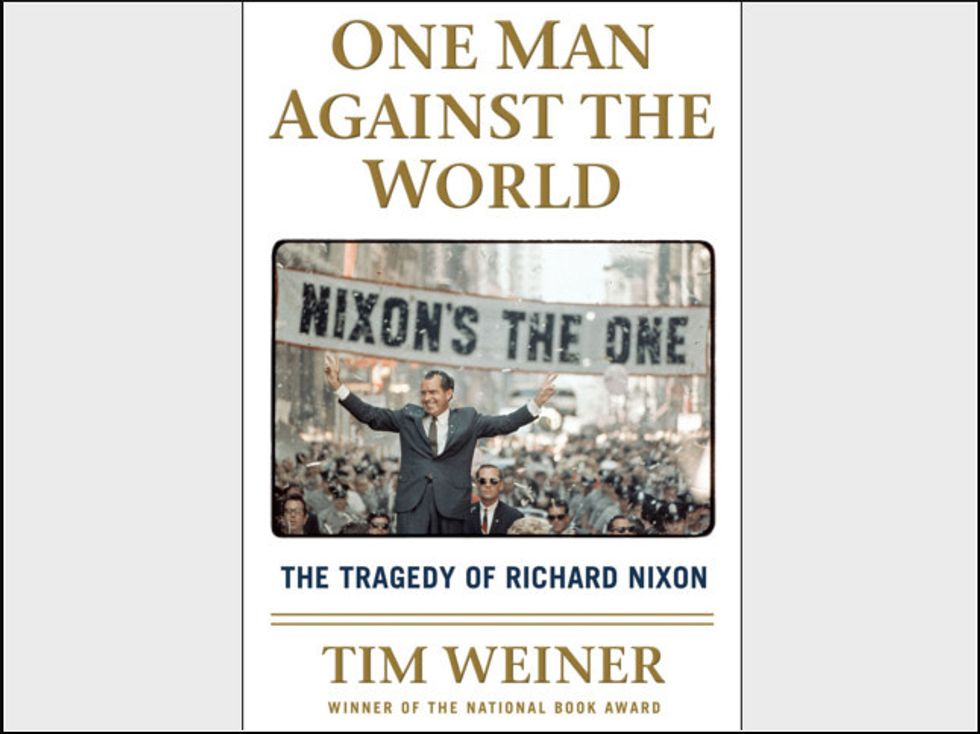

One Man Against the World: The Tragedy of Richard Nixon by Tim Weiner; Henry Holt and Co. (384 pages, $30)

___

The conventional wisdom among Nixon apologists is that the Watergate scandal has been overblown, that the crimes were those that had been committed by other presidents, too, and that Richard Nixon was a great man who did great things. And this certainly would be the judgment that Nixon wanted history to have of him.

But as Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter Tim Weiner expertly shows in One Man Against the World: The Tragedy of Richard Nixon, the late president was an aberration, and his deeds nearly destroyed the country. His chief legacy is not the opening of communist China, but a pattern of presidential abuse of power from which our country is still recovering.

Most books about Nixon suffer from a lack of perspective. Because Nixon wiretapped his own offices and (illegally) those of other people, and his aides took copious notes of conversations, there are reams of documentation of what happened during his administration. Because of this, it is easy to become mired in the details of the Nixon presidency.

Weiner slices through these disparate elements, pulling in only the threads that advance the telling of Nixon’s story. This includes some material that was only declassified last year.

Weiner also avoids the trap of dwelling on the president’s background, noting only how Nixon’s personality — the ruthlessness, the ambition, the political instinct and the amorality — was revealed in his formative years.

Near the beginning of the book, the 1968 presidential election looms into view. Democratic President Lyndon Johnson, his administration undone by the Vietnam War quagmire, had announced he would not seek re-election.

His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was running on the Democratic ticket, hobbled by his loyalty to Johnson and the hatred that the anti-war left bore him. Nixon, the Republican, knew that any peace breakthroughs in Vietnam would hurt his chances for victory.

So Nixon committed what could arguably be considered an act of treason: As Johnson tried to bring the Vietnam parties to the negotiating table, Nixon secretly contacted the president of the corrupt puppet state of South Vietnam and got the South Vietnamese government to oppose any peace negotiations while Johnson was president.

They thought they would get a better deal with staunch anti-communist Nixon in power. Nixon led them to believe this. Johnson found out Nixon’s deeds via intercepted cables and phone calls to and from the South Vietnamese, but he quailed at taking this information public given that it came from spying on American allies.

Humphrey lost the election, and the Republicans took note of the lessons learned from Nixon’s behavior: first, that Nixon’s gambit may have provided the margin of victory and, second, that he had gotten away with it. Nixon would remember those lessons, Weiner notes.

Once in office, Nixon was determined to win the Vietnam War, or at least to have America leave the war “with peace and honor.” To that end, he ordered unprecedented secret bombings of neutral Laos and Cambodia, where the North Vietnamese had bases, bombing on a scale unseen during World War II, even during the atomic bombing of Japan.

He kept his own Cabinet in the dark, conferring only with three of his most trusted aides, and even they did not know all of his secrets. Although he denied it, he sold ambassadorships to the highest contributors in his election campaigns, the ambassadorship to Greece being a particularly egregious example.

As the 1972 election loomed, Nixon ordered massive secret bombing of North Vietnam’s civilian centers to bring the country to its knees. To appease anti-war sentiment at home, Nixon tried the “Vietnamization” of the war — having the South Vietnamese fight instead of American soldiers. But when the South Vietnamese showed little will to fight, Nixon lied to a national television audience, telling the country that “Vietnamization has succeeded.”

Weiner shows in many ways how Nixon conflated his political fortunes with the nation’s interests. For instance, he threw U.S. support behind Pakistan during that country’s war with India because the corrupt and brutal leader of Pakistan had helped Nixon arrange his visit to communist China, and because Nixon personally hated Indians.

He also misused the FBI, the CIA, and the IRS to quash his enemies and any moves against him. Perhaps the worst example of Nixon’s hubris is how he felt about the so-called “Silent Majority,” the people who had voted him into office and supported him during his presidency: “The American people are suckers,” he said. “Gray Middle America — they’re suckers.”

One Man Against the World is studded with gems. But perhaps its best part is the accounting of what Nixon has wrought in this country. Much of the apathy and cynicism, the lack of respect for the office of the president and the distrust of government can be laid at his feet. And then there are the presidents who came after Nixon. It seems that the lessons of Watergate have not been what to avoid, but rather, how much can be gotten away with.

(c)2015 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.