Billy Graham’s Civil Rights Work Picks Up In Ferguson

By Lilly Fowler, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (TNS)

ST. LOUIS — Ferguson is testing the civil rights legacy of famed televangelist Billy Graham.

In a region still roiled by the death of African-American teenager Michael Brown and a recent U.S. Department of Justice report that found a pattern of racial bias among police, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, an organization based in Charlotte, N.C., and headed by son Franklin Graham, is attempting to make a difference.

An emergency team of the ministry’s chaplains has already made two intermittent stops in Ferguson and is prepared to return at a moment’s notice.

Now, the project is taking the next step.

Working with One Church Outreach Ministry, a group that seeks to bring together various Christian leaders and pastors, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association has helped launch an adopt-a-block effort in Ferguson.

For the next six months, a community of Christians hoping to help transform the area will canvass dozens of distinct blocks in Ferguson, offering prayers and assistance.

There are also plans to introduce an adopt-a-school initiative modeled on a national program designed by Tony Evans, a pastor in Dallas at the 10,000-member Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship.

The outreach efforts aim to advance the work Billy Graham began decades ago in the civil rights era.

Billy Graham’s Rapid Response Team, a nationwide group of 1,800 chaplains, races toward disasters, often using tractor-trailers to set up makeshift offices in devastated communities.

The team, specifically trained to deal with crisis situations, first formed after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks in New York. A total of nearly 100 chaplains from different parts of the country have been deployed to Ferguson.

Jack Munday, international director for the Billy Graham Rapid Response Team, says when people experience trauma, they start asking the hard questions.

“People are looking for hope. They’re looking for answers. Quite frankly, they start asking God questions,” Munday said.

The first time Billy Graham’s Rapid Response team landed in Ferguson was in November, when a grand jury opted not to indict Officer Darren Wilson in the fatal shooting of Brown.

A large, black truck with the words “SHARING HOPE IN CRISIS” could be seen on West Florissant Avenue. Chaplains mingled about, allowing folks from the area to climb into their temporary office and talk about their troubles.

“Our mission is to ask good questions,” Munday said. “What they are hearing from us is we’ve recognized that they’ve gone through something and then we listen.”

Chaplains traveled to Ferguson again after two officers were shot last week in front of the police department. The ministry has made an effort to not take sides, reaching out to first responders and protesters.

Stories of success have emerged from the streets.

Chaplains say they have prayed with about 2,000 residents, 100 of whom have chosen to follow Jesus Christ.

There have also been some dramatic moments.

One of the team’s chaplains married a couple, who had been together for nine years and who, in an unrelated incident, had lost their home in a fire, in a Ferguson parking lot.

Chaplain Kevin Williams called the wedding “a signal … to everyone that is paying attention. A change is coming.”

Other times have been more tense. When protesters recently clashed in front of the Ferguson police department, one chaplain was forced to step in, pulling out one woman pinned against a wall by the wrist.

On a recent snowy Saturday, about 50 Christians gathered in a Baptist church in Ferguson. Representatives from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association told those gathered that at that very moment there were hundreds around the country praying for them.

They asked that the Holy Spirit guide the meeting. Among those in the crowd was NFL Hall of Famer Aeneas Williams, a former Rams player who is now pastor of The Spirit Church in Ferguson.

John Galvin, an attorney in St. Louis who has volunteered as a chaplain for seven years, stressed that it was important the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association’s efforts in Ferguson not end with the Rapid Response Team. An adopt-a-block program was one way of continuing their work.

“We stay there until the job is done, and we do it right,” Galvin said.

“Follow-up is the process of giving continued attention to new Christians until they are at home in the local church … develop their full potential for Jesus Christ.”

The plan was for volunteers to painstakingly visit each block in Ferguson, if possible on a weekly basis, and knock on doors. They weren’t necessarily there to spread the Gospel but to show love and offer help.

“You’re not going to force the Bible or Gospel down their throats,” said Jose Aguayo, a chaplain with the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Galvin added, “We don’t compromise on the truth, but we don’t go in with all the answers. If we come in with too much of an attitude, it’s not going to work.”

Those who opened doors would be given information on free early childhood education in the Ferguson-Florissant School District, the Mathews-Dickey Boys’ & Girls’ Club, a summer job league for young adults, and even for a federal energy assistance program.

“I told the mayor, in a year’s time you’re not going to recognize your town, because God is going to take over,” said Aguayo, referring to James Knowles.

(c)2015 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

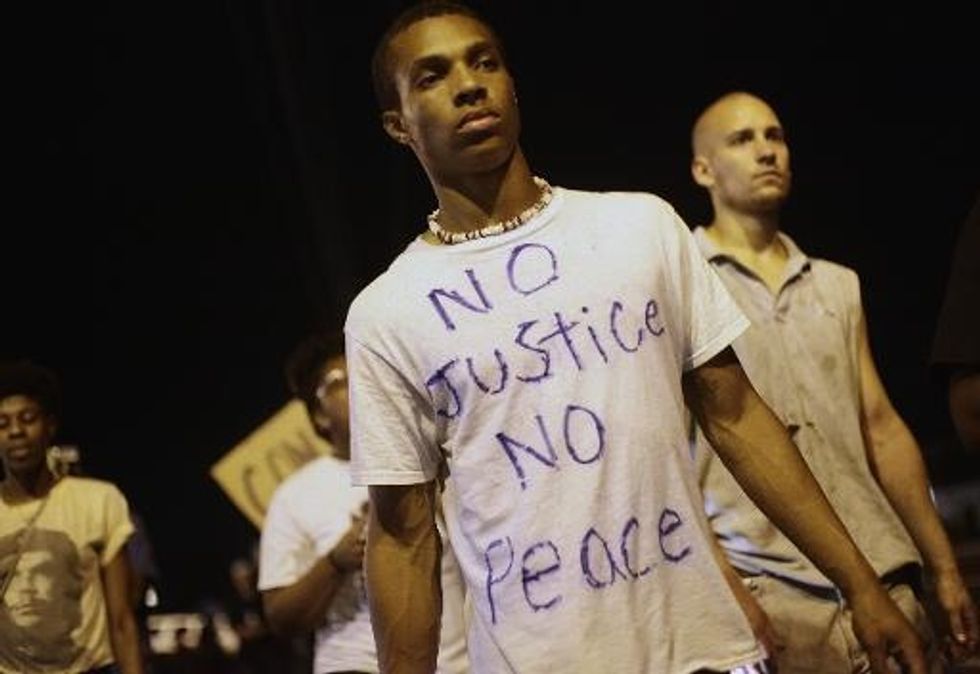

Photo: Genna Adkins, far left, 23, and Leah Coblentz, second from left, 26, listen as Rev. Jose Aguayo addresses participants in the adopt-a-block program at First Baptist Church of Ferguson before they go out into the community on March 14, 2015 in Ferguson, Mo. (Cristina Fletes-Boutte/St. Louis Post-Dispatch/TNS)