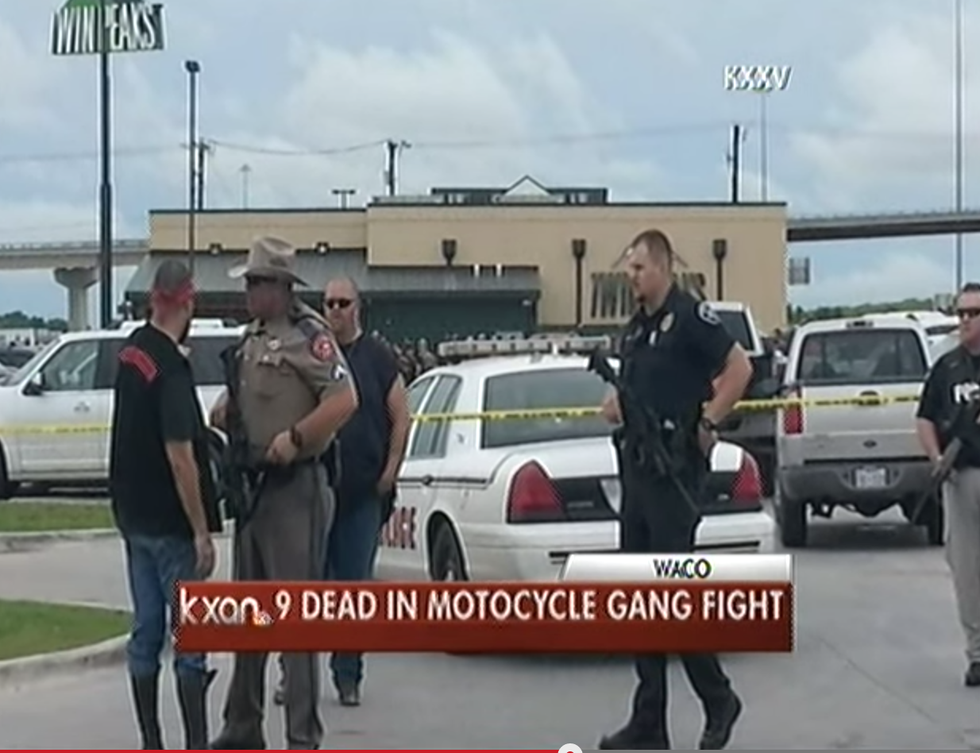

9 Killed As Biker Gangs Shoot It Out In Texas

By Matt Pearce and Molly Hennessy-Fiske, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

WACO, Texas — A motorcycle gathering at a sports bar became a bloodbath Sunday when a bathroom scuffle between rival biker gang members escalated into a parking-lot shootout that left at least nine bikers dead and 18 wounded after police intervened and also opened fire, police said.

“In 34 years of law enforcement, this is the worst crime scene, the most violent crime scene I have ever been involved in,” said Waco Police Sgt. W. Patrick Swanton.

More than 100 people were detained for questioning, some as cooperative witnesses, as investigators sifted through a site laden with bodies, motorcycles, shell casings, knives and clubs in one of the largest showdowns with law enforcement in Waco since a federal siege of a cult’s compound left about 80 people dead in 1993.

The dead Sunday were identified as members of the Bandidos and Cossacks gangs. Swanton said as many as five biker gangs were involved and as many as 50 weapons might be recovered.

Police counted themselves lucky: No officers or bystanders were wounded in the melee, though several cars were peppered with bullet holes in the parking lot at the Central Texas MarketPlace.

But as federal, state and local investigators piece together a messy crime scene, public concern is likely to fall on whether other biker gang members will descend on Waco to seek revenge and why the Twin Peaks sports bar and restaurant had hosted the biker gathering despite a warning from local police.

Police, anticipating trouble, had gathered at the scene in advance. “We knew there would be trouble at this biker event,” Swanton said, adding, “what happened here today could have been avoided.”

Swanton also emphasized that the biker gangs involved were not just local. “This is not a Waco problem — this is a national problem,” Swanton said.

There are more than 300 outlaw motorcycle gangs operating across the country, ranging in size from just a few members to several hundred, according to federal gang estimates. From time to time, investigators land indictments against motorcycle gangs they accuse of doing the type of things street gangs do — committing violence or smuggling drugs.

One 2014 gang threat assessment by the Texas Department of Public Safety took particular concern with the Bandidos motorcycle gang, formed in the 1960s, whose members do dirty work “as covertly as possible” but who proudly wear their colors in public and ride in large packs.

In Waco, police declined to name all the motorcycle gangs involved, though several detained bikers could be seen wearing leather jackets with the words “Scimitars” and “Cossacks” emblazoned on the back.

A law enforcement official who asked not to be identified because he was not authorized to speak said insignia for a gang called the Gypsies also were visible. He said Bandidos and Cossacks are rivals, both self-proclaimed “one percenters” who consider themselves above the law.

“If they have one percenter on their vest, they’re lawless,” he said, adding that members know they’re part of a criminal gang “because they wear it and wear it proud.”

McLennan County Sheriff Parnell McNamara said, “We knew that there was trouble brewing between the Bandidos and the Cossacks, but we didn’t know it would be a shootout.”

On Sunday, some of the gangs appeared to have aligned with each other for a show of force as the bikers gathered at Twin Peaks, a “Hooters”-like sports bar and restaurant known for its scantily clad waitresses, police said. They also might have gathered to recruit new members.

Swanton said investigators, who had been monitoring the biker gangs, had asked the local Twin Peaks franchise not to host the bikers but had been ignored, and had asked the national chain to intervene.

Jay Patel, operating partner of the Twin Peaks Waco franchise, did not address those allegations head-on in a statement Sunday evening, instead writing on Facebook that the restaurant was cooperating with the police investigation.

“We are horrified by the criminal, violent acts that occurred outside of our Waco restaurant today,” Patel wrote. “We share in the community’s trauma. Our priority is to provide a safe and enjoyable environment for our customers and employees, and we consider the police our partners in doing so.”

Of Patel’s statement about cooperating with police, McNamara said, “If he was, I’m not aware of it.”

Swanton was more vehement. “That statement is absolute fabrication. That is not true,” he said.

The massacre began about 12:15 p.m. with a fight in the Twin Peaks bathroom that started as “most likely a push or a shove, somebody looking at somebody wrong,” Swanton said. There also was a fight outside over a parking space, leading to “a fistfight that turned into a knife fight that immediately turned into a gunfight.”

It’s unclear whether bikers were shot by other bikers or by police who rushed to the restaurant at the sound of gunfire.

“As they came up to the scene they were taking rounds and had to defend themselves,” Swanton said of the officers who fired.

Before the shooting, Austin Guerra, 20, of Waco had noticed that multiple police cars had gathered outside Twin Peaks, across the street from where he was shopping at a Cabela’s.

When Guerra came outside, he heard “loud popping sounds” as gunfire broke out for 45 seconds to a minute, he said in a phone interview. Then he saw bikers in leather jackets running everywhere.

After the shooting ended and police swarmed the scene, Guerra said, “You could see bikers sitting all over the place … people in handcuffs, people lying on the ground.”

A handful of motorcycles were still parked in the Twin Peaks lot several hours after the violence.

McLennan County sheriff’s deputies were holding about 20 people wearing leather motorcycle vests — with their boots removed and in flex cuffs — in the parking lot of the nearby Don Carlos restaurant.

Three bikers had already been arrested after the melee Sunday afternoon on suspicion of coming to the scene with more weapons, and Swanton had a warning for other bikers thinking of coming to seek revenge.

“We are prepared to deal with those individuals if they come to Waco,” Swanton said, adding, with a bit of Texas swagger, that “criminal” biker gang members had already “felt the wrath of law enforcement in Waco.”

Later, Swanton added, “We have plenty of space in our county jail.”

(Pearce reported from Los Angeles and Hennessy- Fiske from Waco.)

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Screenshot via