Villaraigosa Bows Out Of Senate Race, Leaving Others To Battle Harris

By Michael Finnegan and Seema Mehta, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

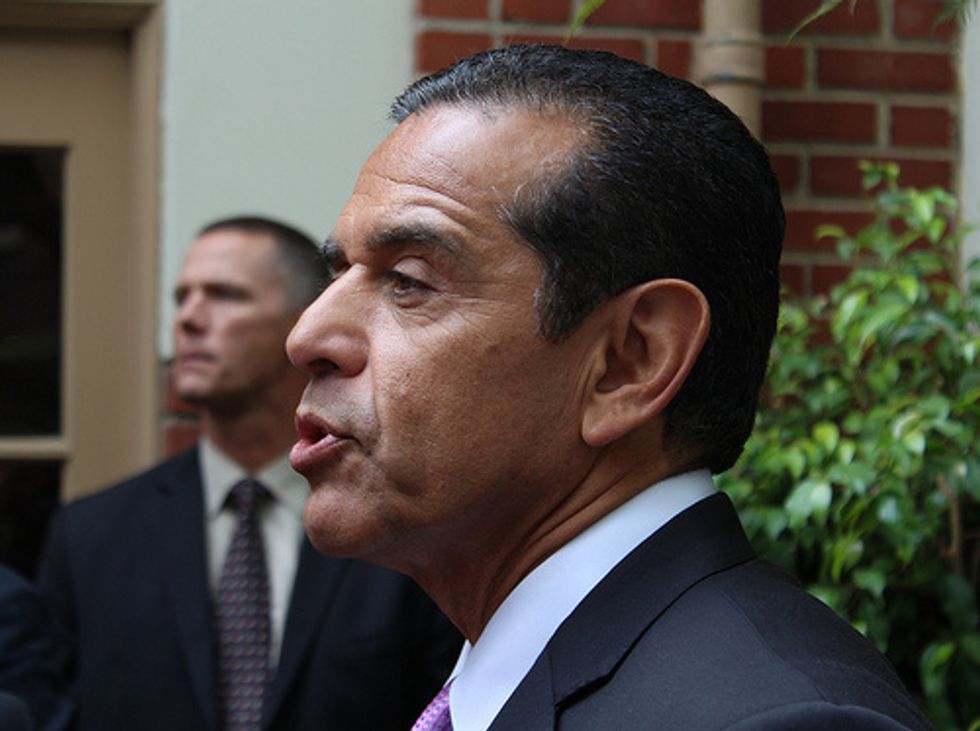

LOS ANGELES — Antonio Villaraigosa’s announcement Tuesday that he would skip the contest for Barbara Boxer’s seat in the U.S. Senate leaves an opening for an array of less-known Californians to take on California Attorney General Kamala Harris, the only major candidate so far.

The former Los Angeles mayor was uniquely positioned to enter the campaign with a broad foundation of support, most solidly among Latinos in Southern California.

But after more than six weeks of private consultations with political leaders and campaign consultants, Villaraigosa, 62, bowed out of contention.

“I know that my heart and my family are here in California, not Washington, D.C.,” Villaraigosa said in a written statement that hinted of his enduring ambition to run instead for governor in 2018.

“I have decided not to run for the U.S. Senate and instead continue my efforts to make California a better place to live, work and raise a family. We have come a long way, but our work is not done and neither am I.”

Harris, a fellow Democrat and former San Francisco district attorney, expects to dominate the Senate contest in the Bay Area, a major advantage in the June 2016 primary. She has been raising money for weeks. She also has a head start in lining up supporters, including law enforcement groups rallying behind the state’s top prosecutor.

Villaraigosa’s exit could draw heightened interest in the race from other Southern California Democrats who are weighing whether to run. They include Reps. Loretta Sanchez of Garden Grove, Xavier Becerra of Los Angeles and Adam Schiff of Burbank.

But all of them lack the public name recognition that Villaraigosa gained in more than two decades as a staple of news coverage in California’s largest media market.

“Any member of Congress is not particularly well-known statewide, so that’s definitely a challenge,” said Parke Skelton, a Democratic strategist who has worked for a number of potential Senate candidates.

Much can occur, however, in the next 19 months. Boxer’s improbable victory in the 1992 Senate race is testament to the potential of relatively obscure House members to vault to the head of the field in a tough statewide contest.

But it’s not cheap to run for Senate, and federal donation limits make it an arduous task to raise money.

“We operate in a completely different political world now, and the amount of money it takes to run and win in California is daunting,” said Democratic campaign strategist Katie Merrill. “I think that’s one of the reasons that you haven’t seen more people jump into the race.”

Still, Harris was elected attorney general in 2010 by a razor-thin margin, and she has yet to be tested in the glaring media spotlight of a big-arena contest like that for U.S. Senate.

The campaign carries little professional risk for Harris. If she loses, she can keep serving as attorney general until her term expires at the end of 2018.

But members of Congress cannot seek re-election and run for another office at the same time, so any who run against Harris must give up their jobs at the end of their current terms.

Of those known to be considering the Senate race, Schiff has the most money in the bank — more than $2.1 million.

Sanchez and Becerra would each depend on a Latino base in Southern California to buttress their candidacies, as would former Army Secretary Louis Caldera, a one-time Los Angeles state assemblyman who is exploring a candidacy. Their big challenge would be to build support among other groups.

“Successful candidates are going to need to move far beyond their ethnic or geographic base in order to win,” said Rose Kapolczynski, Boxer’s longtime campaign strategist.

History suggests the potential election of California’s first Latino in the U.S. Senate could mobilize a disproportionately large share of Latino voters.

Latino turnout typically lags that of other voter groups in California, but a rare exception was Villaraigosa’s 2005 election as mayor, according to Political Data Inc., a nonpartisan company that tracks voting patterns. Villaraigosa was the first Latino mayor of modern Los Angeles, an important dynamic in his campaign to unseat Mayor James K. Hahn.

For Republicans, Villaraigosa’s exit will have little effect. The party’s popularity in California has dropped so low that its prospects for capturing Boxer’s seat are minimal.

Republicans pondering a bid include Assemblyman Rocky Chavez of Oceanside and former state party Chairman Tom Del Beccaro, who have formed exploratory committees. Former state Republican Chairman Duf Sundheim is also considering the race.

For Villaraigosa, the Senate contest would have been his first tough campaign since he ousted Hahn. Win or lose, it would have put the former mayor back in the public spotlight after 19 months of keeping a low profile in the private sector.

It also would have put an early end to his employment as a consultant for Banc of California, Herbalife Ltd. and other companies.

When he left office, Villaraigosa said he wanted to run for governor in 2018 — a timetable that would give him more time to build his personal savings after serving as a state assemblyman, city councilman and mayor.

But Boxer’s announcement last month that she would not seek re-election provided an opening for a quicker return to public office, albeit as one of 100 senators in Washington.

Villaraigosa, however, was put off by the rush to decide whether to run and wanted to stay close to his four grown children in California, said former state Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez, a close friend of the former mayor.

“I think governor is more along the lines of what he wants to do,” Nunez said.

The competition could be fierce. Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a former San Francisco mayor, has already formed a committee to start raising money for the governor’s race.

It appeared to be no accident that Villaraigosa’s statement Tuesday echoed the one that Newsom put out last month when he too declined to run for Senate by saying “I know that my head and my heart, my young family’s future” remain in California.

At the end of 2014, Newsom reported more than $3 million in campaign cash already on hand, as did another potential Democratic gubernatorial contender, state Treasurer John Chiang. Villaraigosa would start the campaign with no money, but candidates can collect much bigger donations for state races than for federal contests.

Other Democrats who might also be tempted to run for governor include Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and state Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de Leon of Los Angeles.

Photo: Paresh Dave/Neon Tommy via Flickr