Supreme Court Sends Missouri Execution Case Back To Appeals Court

Molly Hennessy-Fiske and Seth Klamann, Los Angeles Times

BONNE TERRE, MO — The U.S. Supreme Court stayed a condemned Missouri inmate’s execution Wednesday evening, sending the case back to the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and Missouri officials told those who had planned to witness it to go home.

The high court granted the stay for Russell Bucklew “pending the disposition of petitioner’s appeal. We leave for further consideration in the lower courts whether an evidentiary hearing is necessary.”

Bucklew’s death warrant was to expire at midnight in Missouri, but state officials called off the execution after the Supreme Court issued its order about 6 p.m. Witnesses were not told how soon to return, just that it would not be soon, a state witness told the Los Angeles Times.

A spokesman for the Missouri attorney general’s office said no further litigation was expected Wednesday.

Bucklew’s attorneys had argued that state officials failed to demonstrate they could humanely execute the inmate, who suffers from a chronic, lifelong illness, cavernous hemangioma, which causes tumors in his head, neck and throat that can easily rupture and bleed.

His attorneys also questioned why Missouri officials refused to disclose information about lethal-injection procedures.

Missouri is among several states that changed lethal-injection drugs and suppliers as manufacturers pulled back in the face of international protests. Now they and some other states rely on a single drug, the barbiturate pentobarbital, made by compounding pharmacies not subject to Food and Drug Administration oversight.

One of Bucklew’s attorneys, Cheryl Pilate, told the Times that they were “extremely pleased and relieved” by the court’s decision.

“What this means is that the appeals court will hear Mr. Bucklew’s claims under the Eighth Amendment that he faced a great likelihood of a prolonged and tortuous execution because of the unique and severe medical condition,” Pilate said in a statement.

Bucklew, 45, was convicted of a rampage in Cape Girardeau County in 1996 that included fatally shooting Michael Sanders, his ex-girlfriend’s new boyfriend, in front of Sanders’ 6-year-old son, then kidnapping his ex-girlfriend and raping her before he was captured. A trooper was wounded during the chase.

He would have been the first inmate put to death since Oklahoma botched the execution of Clayton Lockett, 38, last month, provoking outrage and leading that state’s governor to stay the next scheduled execution as well as order a review of Oklahoma’s lethal-injection procedure.

The Missouri attorney general and governor had defended their state’s method of lethal injection.

On Tuesday, Bucklew’s execution had been on again, off again. A three-judge panel of the 8th Circuit imposed a stay. Then the full 8th Circuit lifted the stay. Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon denied Bucklew’s request for clemency. Then U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. imposed another stay.

Bucklew, who came within less than two hours of execution, was held within 50 feet of the death chamber.

A prison spokesman said Bucklew would remain at the prison Wednesday night. He refused to say for security reasons when Bucklew would be returned to the prison in Petosi, where he has been confined.

Among the witnesses sent home Wednesday night were the victim’s two sons, his sister, her husband, an uncle and a cousin, Bucklew’s two brothers, a doctor, a nurse, one of his attorneys, investigators who handled the case and Republican state Rep. Paul Fitzwater.

Fitzwater told the Times that he had awaited the execution in a small room with other state witnesses, apart from Sanders’ and Bucklew’s witnesses. When officials notified them that the execution had been stayed, he said, some witnesses were disappointed. “We waited all day long for this to happen.”

Corrections officials did not tell witnesses how soon they might be brought back, he said.

“It could be 30 days or six months,” Fitzwater said, noting the appeals court has to reconsider the case and the state attorney general has to set a new execution date.

Fitzwater, who leads a legislative committee on corrections, said it would have been the first execution he witnessed. He said he had asked to “see for myself” after receiving numerous phone calls from constituents inquiring about the state’s lethal-injection procedure.

Earlier this year, Fitzwater — a staunch supporter of capital punishment — proposed switching to firing squads. The proposal drew widespread ridicule and did not pass. In hindsight, he said he would not propose it again.

He left the prison Wednesday concerned about what the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision meant for death penalty advocates nationwide.

“This is a setback here in the state of Missouri and across the country. I know people here want to keep the death penalty. They got the wind knocked out of their sails here today.”

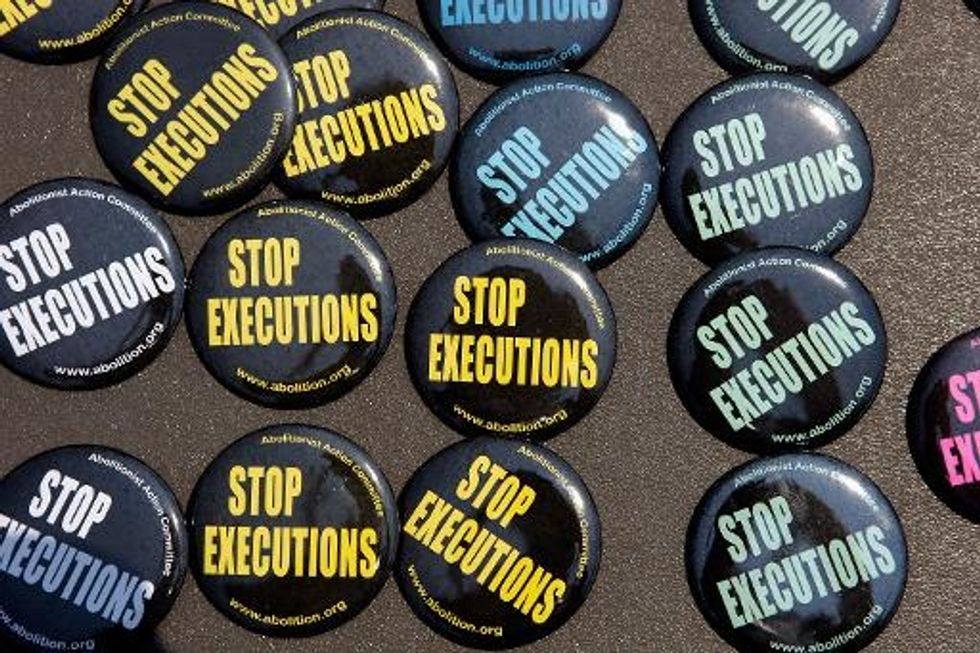

AFP Photo/Chip Somodevilla

Want more death penalty news? Sign up for our free daily newsletter.