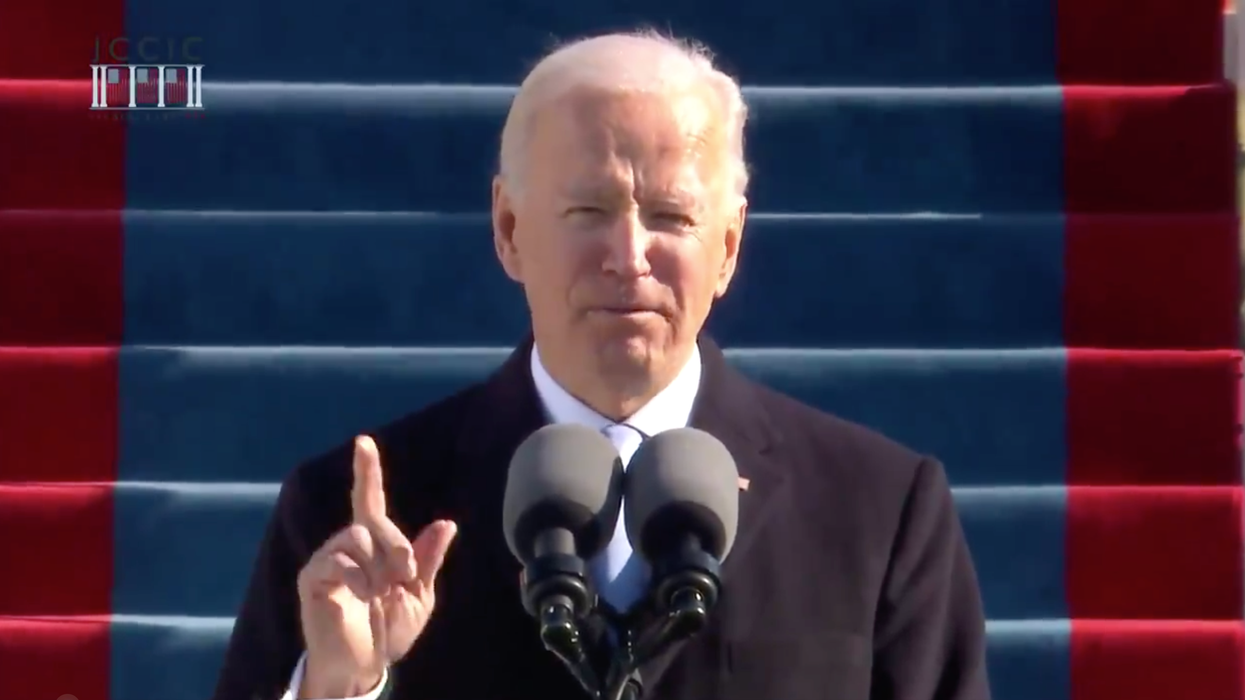

Biden's Speech Confronts Capitol Riot And Calls For End To ‘Uncivil War’

Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

It's become a ProPublica tradition for our president Richard Tofel, who wrote a book on President Kennedy's inaugural address, to offer an instant analysis of such speeches. Here are his thoughts on President Biden's address.

If President Joe Biden's inaugural address was drafted more than two weeks ago, it was certainly rewritten after the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6.

Biden's setting of the scene as "our winter of peril and significant possibilities" may have been the speech's original theme, but its more stark call for an end to "this uncivil war" was surely more recent.

The predecessor most on Biden's mind on this historic occasion was clearly Abraham Lincoln, and the moment was not Lincoln's second inaugural prophecy at the Civil War's end, but his desperate pleas to avoid it ("We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.") at its beginning. Biden quoted Lincoln twice, once from the moment of his signing the Emancipation Proclamation, once from his eulogy at Gettysburg eight months later referring to those who gave "the last full measure of devotion" in the nation's service.

Lincoln was not the only president on whom Biden drew. In this speech — an extended call for unity — the new president hearkened to a tradition first and most memorably encapsulated in Jefferson's declaration, at his first inaugural, that "we are all republicans, we are all federalists."

But Jefferson had followed his assertion of bipartisanship with a sentiment that Biden, after the insurrection two weeks earlier, would not echo: "If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it." Biden, instead, insisted that "disagreement must not lead to disunion."

And he minced no words about where the threat comes from: "political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism." Having thus made clear his belief that race was central to the events of Jan. 6, and implicitly to much of Trumpism, Biden offered no quarter on racial equality. "A cry for racial justice 400 years in the making moves us. The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer," he said.

While that may be nonnegotiable, Biden pleaded repeatedly and directly with the American people for unity even without consensus. A politician for more than a half century, he asserted that "politics doesn't have to be a raging fire, destroying everything in its path." He asserted that this was not a "foolish fantasy," and seemed to recognize that his appeal will fall on some deaf ears. Yet he seems genuinely to believe that there may be "enough of us" for some restoration of civility to be possible. While no one ever wants to quote former President Richard Nixon, he essentially repeated the call in Nixon's inaugural, after the upheavals of 1968, to "lower our voices."

A man of obvious and deep faith, Biden invoked St. Augustine and a recourse to the "common objects of our love." And where the inaugurals of Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and the first George Bush had offered their own handcrafted prayers, Biden led a silent prayer for the 400,000 dead of the pandemic, clearly in the hope that in this the nation might find common ground.

Among the only harsh words in the address came when Biden drew a hard line against what defenders of the previous inaugural at first called "alternative facts." In this, he was biting: "There is truth and there are lies, lies told for power and profit."

It had always seemed likely that Biden would break a tradition extending back seven presidents, to Jimmy Carter in 1977, of thanking his predecessor. Even former President Donald Trump had observed this, citing both Barack and Michelle Obama "for their gracious aid throughout this transition. They have been magnificent." Biden clearly couldn't say that, and didn't. Instead, he thanked his predecessors, Presidents Clinton, Bush 43 and Obama, for their presence, while saluting the fragile and absent Carter, now aged 96.

Beyond the completely unexpected, the great challenge for President Biden, as today made even more clear, is whether his belief that there are indeed "enough of us" willing to abjure "uncivil war" or worse will prove sound, or whether too many will join the previous president in simply absenting themselves from our common endeavors, or worse.