The Secret Science Of Winning The Iowa Caucuses

By Steven Yaccino, Bloomberg News (TNS)

An hour before the Jan. 14 Republican debate, 250 of Ted Cruz’s most dedicated Iowa field organizers huddled in the Heritage Assembly of God church gymnasium in Des Moines. Over a dinner of potato chips and sandwiches, they sat down for a tutorial in caucus-night tactics.

In one sense, the Iowa caucuses, held this year on Feb. 1, are a quaint, almost anachronistic tradition — an assembly of neighbors deciding the next leader of the free world in churches and libraries and school cafeterias catered with hot chocolate and homemade pastries. But they’re also among the country’s most sophisticated, even arcane, political rituals, the culmination of months of organizing. For all the intimacy and homey trappings, they can have the intensity of a high-stakes playoff game.

“It’s laid bare,” says Rick Tyler, Cruz’s national spokesman. “You’ll see who has their pants down and who doesn’t. You’ll see who’s got it together and who doesn’t. I want Iowans to know we’re built to last.”

The tutorial in the church gymnasium was led by Joel Kurtinitis, who four years ago, as regional director for Ron Paul’s campaign, participated in one of the most remarkable coups in Iowa caucus history. Though Paul only came in third in the straw poll, he arrived at the Republican National Convention with 22 of Iowa’s 28 delegates, in part, by a shrewd mastery of the caucus process and the parliamentarian’s Bible known as Robert’s Rules of Order. Paul didn’t win a single primary — and yet ended up with almost as many delegates as Rick Santorum, who won 11.

This year, with the possibility of a contested convention higher than it’s been in decades, and the party verging on disarray, the slightest advantage in the delegate count could be even more important. For that reason Cruz’s campaign is leaving nothing to chance.

The training session was just one of several the campaign has offered in living rooms, libraries, and restaurants around the state, geared primarily toward educating captains in nearly all of Iowa’s 1,681 precincts. For rural areas, teleconferences were available.

On caucus night, turning out the most voters is only the first step. The ultimate trophies are delegates — party members who are elected by each caucus to represent their neighbors at county conventions later in the year. Some of those delegates will become the party faithful who will vote for the next Republican nominee at the national convention. That process begins at the caucuses, where winning delegates can be a whole other game, requiring a long night of political maneuvering and strategic execution.

Paul’s strategy was, at times, one of delay. During caucuses and state conventions, his supporters in Iowa and other states called for “points of order,” challenging procedural errors. They made motions to speak from the floor, and tried to oust presiding officers whom they believed were not sympathetic to their candidate, forcing votes that dragged out the proceedings. By the end, crowds thinned as people got bored and returned home to watch TV or tuck their kids into bed. That’s when Paul’s loyal army, who’d stayed until the bitter end and had the advantage, cleaned up.

This year, to win delegates, Republican campaigns are training Iowa voters to stay until the end of the caucuses — past the presidential straw poll, platform votes, and other party business. The first hurdle is finding supporters to nominate for delegate positions in every precinct. In more populated areas, mini-campaigns are mounted inside each caucus for a ticket to the county convention. Rural settings, however, are often desperate for delegate volunteers.

Each delegate is then voted on by the assembly. In some cases, to stop one candidate from collecting a majority of delegates, precinct captains from rival campaigns have struck deals and joined forces, using colored signs or text messages to signal when to cast their votes.

The delegates who emerge from the caucuses still have to run a gauntlet of conventions at the county and state level before reaching the Republican National Convention in Cleveland this summer. But while new GOP rules bind those delegates to the results of the caucuses for one ballot, delegates are not required to disclose who they would support in subsequent rounds of a contested convention.

The rules are a bit different on the Democratic side, closer to simple horse trading. Precinct captains have been known to encourage their supporters to back a rival candidate in order to keep a third candidate from picking up more delegates, or forming alliances with other campaigns, then splitting the delegates.

“What is the ratio in the room? What is the tone in the room? This is a very human process,” says Julie Stauch, a spectacled home gardener featured briefly in Hillary Clinton’s presidential announcement video, who has been hosting caucus training sessions at her home over the past six months. “You have to be informed. You have to understand who your candidate is, what they’re about, who your opponent is, and how to convince their supporters.”

Democrats choose their delegates in each precinct by making campaigns gather their supporters in separate corners of the room to be counted. There will also be a place reserved for anyone who is still not decided (uncommitted groups won the Democratic Iowa caucuses in 1972 and 1976).

Each precinct has a “viability” threshold that candidates must reach in order to be eligible for delegates. In most precincts, that amounts to 15 percent of the vote. If the threshold is not reached, supporters of ineligible candidates are free to support someone else, creating a bidding war between campaigns on the caucus floor.

When persuasion doesn’t work, more creative methods are called into play. Stauch gets almost giddy as she recalls elections when she forced bidding wars for her votes. A Wesley Clark supporter in 2004, she agreed to realign with John Kerry’s campaign if they helped elect two Clark supporters as delegates that night. Precinct captains for John Edwards and Howard Dean decided that price was too steep. More than a decade later, Stauch shakes her head remembering Dick Gephardt voters who walked out halfway through her local caucus that year. “They could have gotten something,” she says, still annoyed years later by the wasted opportunity. Statewide, Edwards lost the Iowa caucuses that year to Kerry by about 5 percentage points.

Stauch relays past caucus stories each month during her living room training sessions, which about 70 people have attended this cycle. One week they played “Jeopardy!” with facts from Clinton’s biography. Another week, the group rehearsed caucus night speeches. Last month, they played a card game she invented — caucus poker, Stauch calls it — to practice viability math and different negotiation scenarios.

Sometimes, when Clinton’s Iowa campaign is working late on data entry, organizers and volunteers will hold practice caucuses over what movie to watch or which restaurant they’d like to order dinner from. Other times, they rehearse caucus strategies, substituting gummy bears as stand-ins for Iowa voters. Earlier this year, Clinton’s Iowa staffers divided into corners of the room during a mock caucus to pick their favorite presidents — The West Wing’s Jed Bartlet, House of Cards’ Frank Underwood, and Veep’s Selina Meyer were all front-runners.

Joan Amos, a sweet, outspoken 73-year-old chair of the Democratic Party in Lucas County, attended one campaign caucus briefing a few months ago and told me Clinton volunteers are being encouraged to vote for Martin O’Malley in cases where making him viable would prevent his voters from shifting to Bernie Sanders.

Amos says that, at least in her county, food can also be a strategic consideration. A neighbor once gave her an expensive bottle of wine and asked her to switch her vote to a rival campaign (she didn’t). In 2008, she said the Clinton supporters in Lucas County separated their home-cooked dishes from the main community potluck table on caucus night in order to make their corner of the room look more inviting. When I asked if the Clinton campaign intended to bring food this year, one local volunteer, Susan Cohen, clarified: “It’s not bribery, it’s all about hospitality and making it a good experience for everybody.”

The Sanders campaign, in turn, says its focus is split between trying to demystify the caucuses for first-time supporters and train precinct captains, some of whom are also attending their first caucus this year, to make sure the process is as smooth and accessible as possible to newcomers.

“If there’s disorganization, you might lose people,” says Fred Trujillo, a first-time precinct captain for Sanders in Des Moines, who has attended a handful of training sessions by the campaign and nonprofit groups.

The central message the Sanders campaign is putting forth to its supporters can be summed up simply: caucusing is easier than it sounds. “If you’re showing up for the first time, it’s not like you’re going to be crunching numbers,” said Rania Batrice, the Sanders campaign’s Iowa spokeswoman. “Just find your candidate’s sign, stand next to said sign, you’re caucusing.”

The Iowa GOP insists it will be more prepared this time to handle the kind of procedural fights that Paul instigated in 2012. “It almost ruined our party,” says Jeff Kaufmann, chair of the Iowa Republican Party.

“I think it’s less likely to happen this year,” Kaufmann continues, noting that the party will have held more than 300 caucus-training sessions for precinct and county chairs by February, so they won’t be surprised by parliamentary gambits.

The success of Ron Paul’s strategy has at times been overstated; in 2008 and 2012, while causing headaches for GOP nominees, he collected nowhere near enough delegates to win the nomination. But with Republican leaders now planning for a possible contested convention this summer, every delegate may matter in the end.

“It’s something that anybody looking at a long-term strategy, not a short-term strategy, would do,” said Ryan Rhodes, Iowa state director for Ben Carson’s campaign, which has held more than a dozen trainings around the state. “We’re not just preparing for a flash-in-the-pan campaign. Delegates are not bound after the first ballot. You don’t want another campaign having any sway over those delegates if there’s a floor fight. Anything else is just short-term political thinking.”

The Cruz campaign says it now has more than 10,000 volunteers knocking on doors and phone-banking statewide. “We will know, to the best of our ability, who our voters are coming in and our precinct chair will know who to look for,” says Cruz Iowa state director Bryan English, sitting in his office at Cruz’s Iowa headquarters, a well-mannered but bustling single- story building in a suburb near Des Moines. On his desk, within short reach, is a copy of Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War.”

Toward the end of our conversation, English was asked how the average Cruz supporter was going to know which delegates to vote for on caucus night. He smiled, then deflected. “Ask me that again in February,” he says, “how that process worked.”

©2016 Bloomberg News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

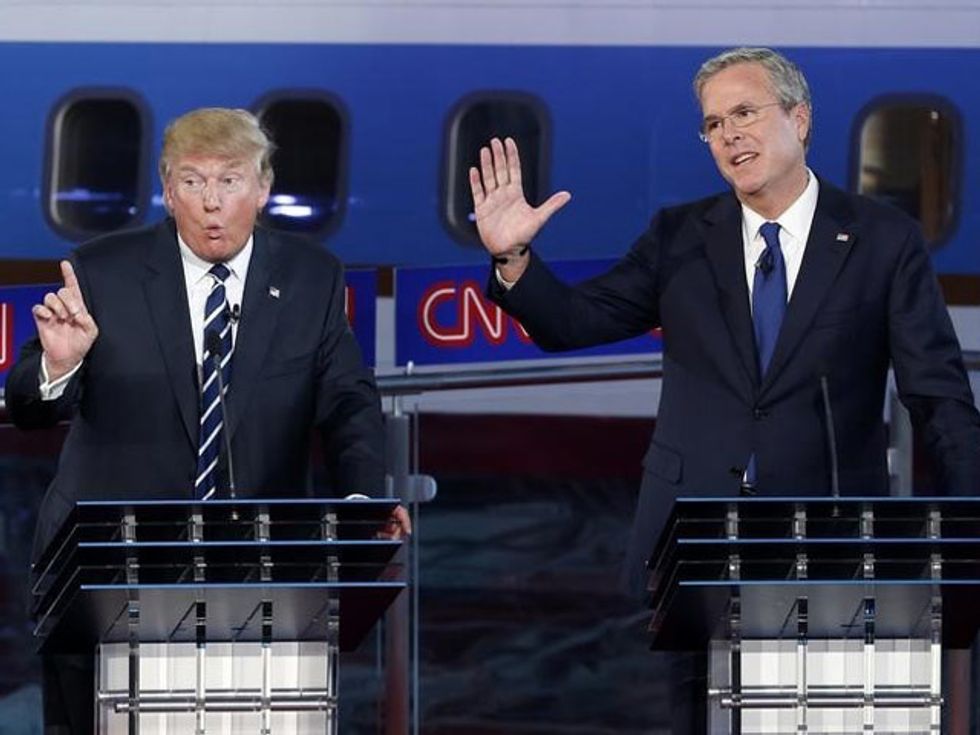

Photo: Republican U.S. presidential candidate Senator Ted Cruz waves to the crowd at the Fox Business Network Republican presidential candidates debate in North Charleston, South Carolina, January 14, 2016. REUTERS/Chris Keane