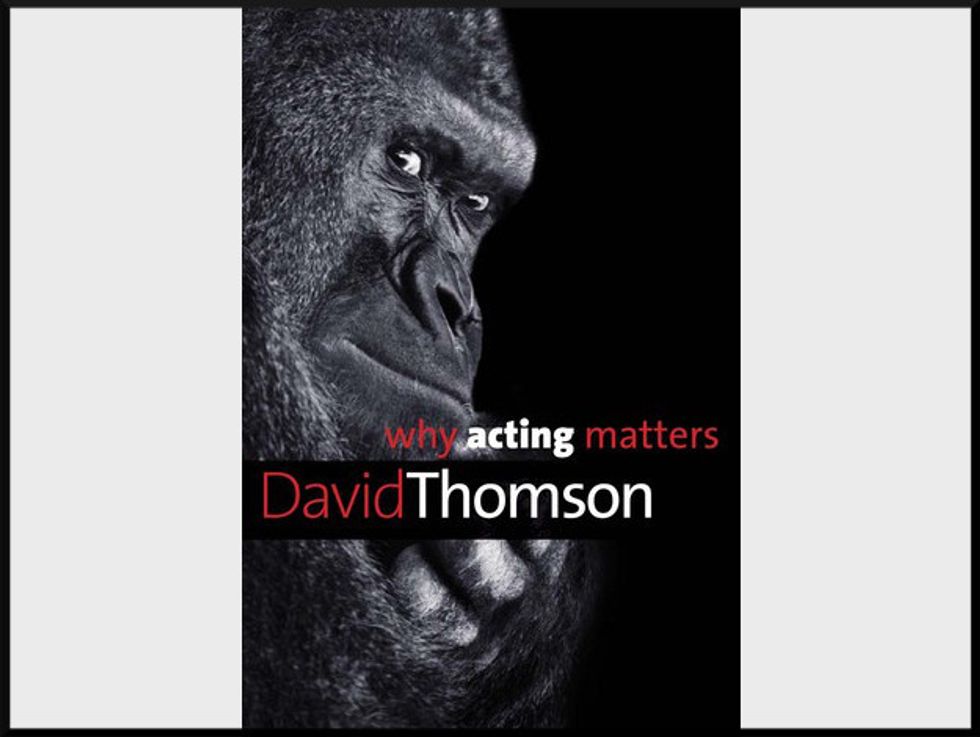

Book Review: ‘Why Acting Matters’

The cover of David Thomson’s beguiling new book, Why Acting Matters, features Andy Serkis as Caesar, the rebel ape from Matt Reeves’s Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), looking at us from some primitive threshold: preoccupied, questioning, stuck on some decision. Do we believe him to be Caesar? How else does his otherness reach us? How many want their lovers to look at them the way Naomi Watts looks up at Serkis as King Kong (2005), even though we all know she’s flirting with some scrawny British actor miming against a green screen (for CGI dubbing)? How did we arrive at such elaborate pretending?

Drunk on pretense, stabbing the vein of the craft’s wildest ambitions and anxieties, Thomson writes as the thespian’s greatest advocate, the critic as idea engine who launches a thousand arguments. In one of many subtexts, he hints at how much writing resembles acting: the assumption of a voice, the deliberate staging of a narrative, the occasional improvisational flights, the coy suggestiveness alive in his stylistic mask. Ideas become protagonists, heroes armed with possibility, poetic allusion, and history’s wisdom. He overplays, he underplays, he succumbs to celebrity wile, then punctures its pretense; he masters the large characters (John Barrymore, Meryl Streep and Vivien Leigh) without slighting the incidental players who provide definition, context, and reliability (Frederic March, Regis Toomey). And his prose prods themes forward with deft momentum, leaving us hanging, wanting more, holding back to preserve the finer mysteries, in prose sharp enough to jog memory and rich enough for private meanings. As author, Thomson plays Citizen Kane, Charlie Chaplin’s tramp, even Hamlet, all commanding and indecisive, alone yet entreating an audience to understand with him, in ways only the most imaginative actors dare to inhabit the mind’s many stages.

At 73, Thomson speaks with authority’s ease. Perhaps you know his definitive Biographical Encyclopedia of Film, now in its sixth edition, a timeworn resource for viewers, actors, directors, producers, and casting agents. Or perhaps you’ve read one of his major biographies of key cinematic figures (Orson Welles, David Selznick, Warren Beatty, Nicole Kidman), scattered profiles, or numerous think pieces posing as movie reviews (up until recently, for the New Republic). Thomson’s prose dips and soars, as much in his beguiling rhetorical questions (“Are we in control of the life we are leading, or does it occasionally run away with us?”) as his fiendish asides: “…We still believe that actors are more interesting in interview than musicians. (I fear the opposite is true—many actors are dull without scripts, especially the devout improvisers.)” He pinpoints the allure of Julia Roberts (“gorgeous beyond belief, where ‘gorgeousness’ was like a mainline into one’s hopeless desires”), and rails against phony sincerity (“[Margaret] Thatcher was… acting her head off. Nobody talks like that”). Sometimes, alarming understatement stitches everything together: “Citizen Kane is more subversive than any American play of its era.” Just as Woody Guthrie trumped John Steinbeck.

The book bulges with stage and film lore by isolating the peculiar distinctions between the classic British approach to the craft (through Sir Laurence Olivier) and its American reaction (the Actor’s Studio Method, through Marlon Brando). Thomson came of age in London (and wrote a memoir of his 1940s-1950s London as an only child in Try to Tell The Story, 2009). But he’s taught, directed, and practiced criticism chiefly in America, and has called San Francisco home for decades. His immersion in Hollywood has led to two fine histories of the medium: The Whole Equation (2004), and last year’s The Big Screen (2014), a seductive meditation on how the art of dancing light has stretched our capacity for wonder.

Here as before, Thomson demurs from clichés about “inhabiting” character and “submerging” in roles to the more complicated tensions between seeming and being, acting for fun (which we all do), and acting for very high stakes (ditto, with our lovers). He’s fascinated by how actors struggle with roles, the distance between their conceptions and their characters, and how to express this creative tension in a meaningful way with their audience. Unlike most books on acting, it contains very little practical advice and a surfeit of poetic wisdom, how the ideas behind acting can illuminate how we perceive ourselves and others. As you read, you’ll second-guess your own treasured memories of performances, and re-screen classic films to grapple with his ideas.

“…We take pleasure in watching the role and the player wrestle together,” says Thomson. “Sometimes in movies it is as erotic as ‘lovemaking.'” Every actor depends on the good will of the audience to partake in their charade, and the process of pretending, both as actors and viewers, animates a deeply satisfying human need for storytelling. In short, if acting, as Shakespeare believed, reaches beyond its obvious metaphors for life, our engagement with acting expands “acting” into a philosophy of art, or how to explore one’s inner life with others. “Perhaps acting matters because of our dying attempt to believe that life is not simply a desperate terrifying process in which we are alone and insignificant,” he continues.

This leads Thomson to complicated notions, at one with both cynicism and romanticism about his subject. “Acting is so essential or inescapable that it easily absorbs and welcomes bad acting. So let us toss out that old chestnut that the play or the actor may help us ‘to live better.’ There is no help. The purpose of acting is to evade such considerations —a nd you can see how fruitful it has been.” In other words, we tolerate bad acting (just like we do bad criticism) while subscribing to its necessity — all day long on television, all night long on cable, across streaming mobile, and across vast iMaxes in 3D, we lurch from story to story, so many that even the profusion of today’s technology can scarcely accommodate it all. The more technology we throw at it, the further behind we fall. The Netflix firehose never quite quenches our outrageous demands on story.

In one well-known fable, Thomson describes how Olivier came to portray Archie Rice in The Entertainer. Olivier met the playwright, John Osborne, backstage in 1956 after Look Back in Anger, a trendy piece of working-class resentment then scandalizing establishment London. Bowled over by the sheer sensation of the piece, Olivier blurted out “Maybe you could write something for me…” Osborne then created Rice, a has-been music-hall clown indifferent to the Empire’s Suez crisis. As Thomson observes, “Osborne retaliated as if to say, ‘Well, see if you can play this.'”

As Rice, Olivier’s pique and radiant self-contempt made stick figures of Osborne’s stage “rebels.” If the generational voltage of Anger had stumped the wry, reflective, future Knight, Archie Rice was a “typical” character he knew too well. Thomson’s description of Olivier’s Rice swells with detail: he “wore a bowler hat, a loud check jacket, a bow tie like a dildo, a cane, and a rictus grin. He was odious, slimy, pathetic, and the lowest life Olivier had ever chosen to play. But he was an arresting, insolent scoundrel, dishonesty made supreme.” And half of Olivier’s zeal lay in his understanding that Rice stood for Britain itself, a hollow empire that persisted well past history’s reckonings. As Thomson puts it, “Archie speaks to a moment in British history when the imperial bedrock was cracking and a famous actor felt the appealing risk in discarding his own heroic aplomb…” Olivier and Rice converged person and symbol.

When we think of the “great” Olivier performances, the contemporary adjectives describing his mannerisms seem quaint. During the height of his 1964-65 Othello, “…it seemed then like an unprecedented portrayal of the blackness… Now it seems fussy and condescending.” So looking back always involves distortion, imposing our reality against previous realities, with all their assumptions, prejudices and self-satisfactions. We also tend to remember Olivier as an epitome of greatness, but the Gods hurled their own arrows upon him like any other player: “Years earlier, Garbo and the director Rouben Mammalian had decided that Olivier didn’t have enough excitement on screen to play with her in Queen Christina. He was callow next to her. Not sexy enough for Garbo — that’s a tombstone line, and a spine of insecurity.”

In leafing through layers of the historical idea of acting, Thomson reaches back to Edmund Kean (1787-1833), the first “Shakespearean” actor. But even Kean seems dreamt up by the playwright himself, or as Thomson put it, “…one dramatist introduced the prospect and potential of acting beyond any other playwright because the nature of being and acting was itself the Shakespearean subject.” Of Kean, Thomson writes “…in many of the pictures he looks like someone trying to assert the fact that he is an actor. You can tell from his expression that any actor fights a battle of belief—with the audience and with himself.”

As he switches from Olivier to Brando (who had worked with Olivier’s wife Vivien Leigh onstage in A Streetcar Named Desire), Thomson exhumes more treasure. As a Brit ransomed by the American imagination, he remembers Brando’s stage presence as alarming, crucial to our understanding of his persona. But these impressions don’t carry forward: “For those there on the first night of Streetcar or during the first run, Brando was the center of attention,” Thomson writes. “But that was not fair to the play they were playing, and it is far from the historical record. A Streetcar Named Desire is established as one of our great plays and in the years since it premiered, our sexual nature has been treated with so much more candor that it’s possible to see both overt action and dream metaphor in the play.”

By the time Brando sealed his persona with “I coulda been a contendah…,” Thomson writes, “The standard for truth or realism in acting shifted…so that many people saw Brando as more modern than Olivier, more in tune with rough, unschooled emotional existence…” But Brando’s “Method” (and the Actor’s Studio) became more like a “church” than technique to many, Thomson argues, with varying results. The problems lay at least as much in the theory itself as in the many temperaments who undertook it as gospel: “…The notion that the actor had become the real thing might be sentimental and simpleminded,” he argues, “and an evasion of the more paradoxical principle: that you had to be real and fake, at the same time.” Recall Olivier’s famous comment about Dustin Hoffman “cogitative delays” on the set of Marathon Man: “Oh gracious, why doesn’t the dear boy just act?”

What for 1947 seemed a “vivid example of the contrast or conflict between American and English acting,” between Olivier’s thought and Brando’s physicality, has faded into the mist of conjecture. The pornography of everyday life now obscures what was once great about Brando, just as much as it does about Elvis, and Beatle haircuts. Except for this pearl: “[Brando] was a great actor more than he was a Method actor.”

Much of Thomson’s subject transcends acting to address history itself: “So it is a history of increasing lessens and it goes on and on,” Thomson writes, “yet somehow every master of underplaying looks like a ham thirty years later…” We always seem to live in an age of “greatness” in acting, yet each era eats its young. Would that we someday find ourselves as impressed with scripts as with the performances that too often prop them up.

If Brando’s eccentricity never quite satisfied Hollywood’s yawning infantilism, his long, insidious slump into flaky self-parody provides a useful contrast to Olivier’s work ethic. “If there is a vital difference between Brando and Olivier, it is in the fact that Olivier never yielded to that contempt, to its eventual self-loathing, or to a fatigue with pretending…” As different as these two figures remain in the theatrical imagination, “…they were very alike in that their own reality had succumbed in so many ways to the career of pretending…”

This sends another enticing question to ricochet off the rafters: “What would you have given to see them together as Vladimir and Estragon, the tramps in Waiting for Godot?” Well, the Gods had a confounding answer to that too: The dream pairing of Ian McKellan with Patrick Stewart in director Sean Mathias’ production felt like a Disney theme park of cheery existentialism. Here was Beckett’s comedy minus an essential thread of meaninglessness, and no cackling void.

Few critics adore actors the way Thomson does, and few chisel away at the contradictions alive in his adoration: “We believe that these people are gentle liars and addicted pretenders. And in making these assumptions, we infer that the ‘others,’ the audience, are sober, honest, down-to-earth citizens whose worst instincts for dishonesty are exercised and even exorcised by the actors. Actors are the spokesmen for fiction itself in a world where we cling to the myth of fact…”

So, why does acting matter? Thomson’s indefatigable questions chase things every which way: “Could it be that we fall apart without it?” Thomson asks. “But does that mean that all our experiences have become like scenes from the play of our lives? After all, soon we will be gone, and are we then a play that was never recorded?” Or does Andy Serkis, playing Kong too well, seize that ape’s inexorable gaze to chasten us, or mock?

NPR critic and Emerson College journalism professor Tim Riley has written five critically acclaimed books on rock history, including Lennon: The Man, the Myth, and the Music (Hyperion, 2011). His commentary appears in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Truthdig, and Radio Silence.