Weekend Reader: ‘Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Beatles And America, Then And Now’

Fifty years ago today, four mop-topped lads from Liverpool with a loud new sound — the Beatles — made their American television debut on CBS’ The Ed Sullivan Show.

Even before the hugely successful broadcast that Sunday evening, a sense of history hung in the air, as hundreds of young fans set up camp outside the Plaza Hotel in midtown Manhattan, where the Beatles were staying, just blocks across town from the Ed Sullivan Theater on Broadway. More than 50,000 requests for the 700 available studio audience seats at that first show had piled up in the producers’ offices, with celebrities such as Walter Cronkite and Jack Paar pleading for tickets on behalf of their teenage daughters (among the fortunate handful who got in was Julie Nixon, the future president’s 15 year-old daughter).

Having worked in broadcasting and newspapers for decades, Sullivan was stunned by the pandemonium that suddenly engulfed him and the city, as he admitted while introducing the Beatles for the first time: “Now yesterday and today, our theater’s been jammed with newspapermen and hundreds of photographers from all over the nation, and these veterans agreed with me that this city never has witnessed the excitement stirred by these youngsters from Liverpool who call themselves The Beatles,” he said. “Now tonight, you’re gonna twice be entertained by them. Right now, and again in the second half of our show. Ladies and gentlemen, The Beatles! Let’s bring them on.”

Opening with “All My Loving,” the first set then spotlighted Paul McCartney singing “Till There Was You” and concluded with their number-one hit, “She Loves You”; the second set, closing the show, included “I Saw Her Standing There” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” — all accompanied by an endless cacophony of high-pitched adolescent screams.

Who knew that was how a revolution would begin?

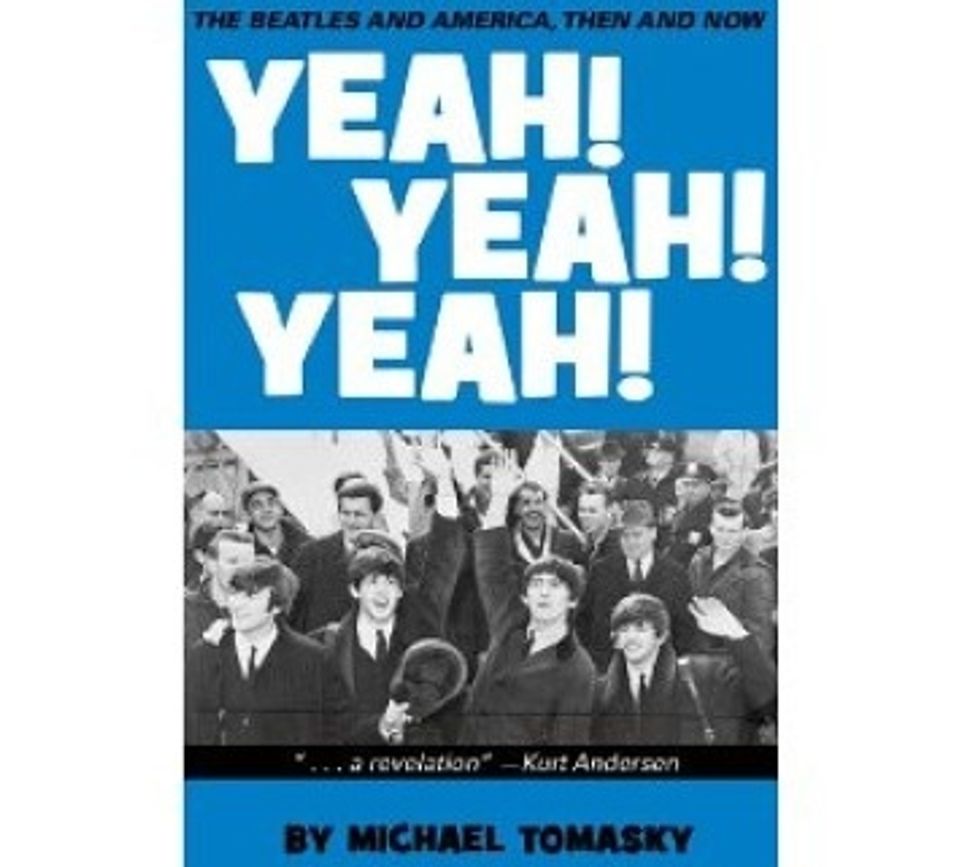

In honor of this poignant yet happy anniversary, Weekend Reader features an excerpt from Michael Tomasky’s terrific new e-book, Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! The Beatles and America, Then and Now — available for $5.49 on Amazon.com.

How big an event was The Beatles’s first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show? The numbers are still staggering: More than one-third of the country watched—73 million people, in a nation then of 191 million. The equivalent today would be 100 or 105 million people watching something. That is true only of Super Bowls, typically viewed by 110 to 120 million Americans now (112 million, this recent one). The M*A*S*H finale in 1983 is still tops, percentage-wise; it got nearly half the country, 106 million out of 234 million. But outside of those two examples, nothing else quite stacks up, 50 years later.

The appearance lit a fire that raged across the country. Suddenly that back catalog of songs, the tunes that Capitol Records exec Jay Livingstone had insisted throughout 1963 wouldn’t do anything in America, now proved rather handy for the label, and for a few other clever ones as well. A label called Swan had purchased the rights to “She Loves You” in 1963, after Capitol took a pass. Swan immediately rushed out “She Loves You,” and, immediately, it went to #2. In late March it even dislodged “I Want to Hold Your Hand” from the top spot. Vee-Jay brought out “Please Please Me,” and a Vee-Jay subsidiary called Tollie released the band’s cover of the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout.”

On February 21, the group flew home. By then they had the two top spots on the singles chart. By February 29, they had numbers one, two, and six. On March 7, one, two, and four. On March 14, one, two, and three. On March 21, one, two, three, and seven. On March 28, one, two, three, and four. That was mostly back catalog. March brought the release of a new song, “Can’t Buy Me Love,” and on April 4, the group claimed the top five spots on the Billboard singles charts, which had never happened before and has never happened since.

The album charts told a similar story. On February 1, The Singing Nun was at the top. The only rock’n’roll records in the Top 10 were the Beach Boys’ Little Deuce Coupe and Elvis’s Fun in Acapulco soundtrack; calling the latter rock’n’roll is being perhaps a tad generous, but he was The King, so let’s give him that one. Peter, Paul, and Mary had three albums in the Top 10. Two positions were held by none other than John Fitzgerald Kennedy. One was the BBC’s tribute to JFK performed by the cast of the innovative current-events television series That Was the Week That Was, which featured David Frost and Roy Kinnear (who the following year played the pudgy bumbling scientist in Help!). Why it was credited to Kennedy I’ve no idea. The other was an album of excerpts of Kennedy’s most important speeches. Joan Baez and the West Side Story soundtrack rounded out the Top 10 of that final pre-Beatles week.

The next week, Meet the Beatles! was at #3, and finally, on February 15, the group sent Soeur Sourire scurrying. Meet the Beatles! stayed #1 for 11 weeks. It was dislodged by … The Beatles’ Second Album, more back catalog. It stayed #1 for five more weeks. On May 2, the group held three of the top four album spots: the Second Album at #1, Meet at #2, and Introducing … The Beatles at #4. The fever finally broke in early June—until late July, when A Hard Day’s Night came out and nailed down the top spot for 14 more weeks, into late October. So 30 of the 52 weeks of 1964 had a Beatles album at the top of the charts.

What did grown-ups make of all this? The idea that this was all potentially quite subversive wouldn’t really take root for another year or two. So the general posture of the adult world, in early 1964, was a kind of dismissive indulgence; let the girls get this out of their systems, and in a few months’ time, those Beatles will be back home and will have gotten decent haircuts and jobs down on the docks, or wherever it was that the young men of Liverpool worked. Entertainers poked fun at them. A little hip gyration or head shake from an adult, on TV or at a party, accompanied by a “yeah, yeah, yeah,” would set the other adults to laughing or rolling their eyes.

This mockery was also the basic posture of the protectors of high culture in America. In those days, The New York Times did not write about this sort of falderal; neither did The New Yorker or any other serious magazine. “Music” was classical music, jazz, and Broadway.

The Times covered, with considerable head-shaking bemusement, their arrival in New York as a news event (whatever several thousand girls screaming at an airport was, it was certainly that). And it made one exception to its rule about what constituted music in this single high-profile case—Theodore Strongin, one of the paper’s music critics, filed a brief, 324-word report on February 10 that attempted (although not really) to take the group seriously as music, delivering verdicts like: “The Beatles’s vocal quality can be described as hoarsely incoherent, with the minimal enunciation necessary to communicate the schematic texts.”

But some people knew; they could see that this was an earthquake. Ten or so years ago, I had the opportunity to talk to Nora Ephron about all this. She covered the group’s arrival in New York as a young reporter for the New York Post. Over the course of the four days they were in the city, she was assigned to follow them wherever she could, so she got to know them. She was exactly their age, and she was attractive; so naturally, she recalled, they teased her and flirted with her. The press conference and photo session in Central Park, the one where it was just the three of them without George, who was sick in bed back at the Plaza; she showed up late for that one, she remembered, and ran, embarrassed, into the gaggle as they needled her. You can practically hear them, in that sing-songy Scouse accent they made famous: “Oh, look, Nora’s come.” “Good of you to join us, Nora.” “So, Nora, can we start, then?”

She was enchanted. I don’t remember her exact words. I do remember, very clearly, the rapturous look on her face—the look of someone recalling a still-loved old flame or a cherished memory. And I do remember her saying that yes, she knew instantly—there was something different about them. She was way too old for their music at that point, even though she was their age. But all the same she could tell that this was something new, and life was about to change.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can purchase the full e-book here.

Michael Tomasky is a columnist for The Daily Beast and editor of Democracy: A Journal of Ideas. Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! is his first e-book.