Why Ex-Offenders — And Prisoners Too — Should Have Voting Rights

The Democratic primary race bumped into voting rights for incarcerated people again this week at a CNN Town Hall. Bernie’s on board, Mayor Pete’s a hard no, and both Sens. Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren said the idea warrants further “conversation” in the future.

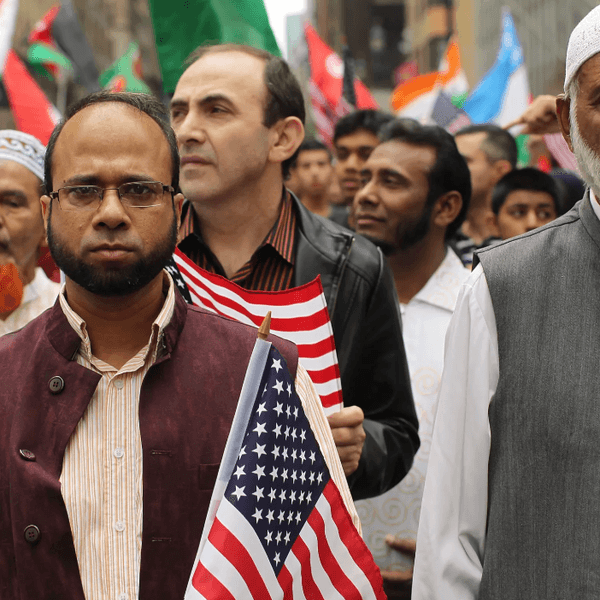

Since it’s Second Chance Month, the annual awareness month dedicated to the stories and challenges of people who are leaving correctional custody, I think we should talk about it now. I want to discuss civic participation as a rehabilitation strategy and voting rights for prisoners as a way to keep people from reoffending.

When we talk about reentry, we think about the structural barriers like employment, housing, identification cards.

These are legitimate challenges for the returning citizen. As many as 27 percent of people released from prison are unemployed despite a cushy job market. Formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. Even what seems like an easy hurdle to clear — securing an ID card to start the job and housing search — can be next to impossible.

Because social service agencies are so focused on helping people over those hurdles, we miss opportunities to talk about the fact that so much of reentry is emotional and psychological; the biggest barrier is self-concept. A criminal record ostracizes a person relentlessly.

Disenfranchisement is an extension of the criminal label and reinforces the idea that a person will continue to live outside the law. This might explain why people released from prison in states that permanently disenfranchise people — such as Iowa and Kentucky — are roughly 10 percent more likely to reoffend than those released in states that restore their rights, according to one study.

Our memories are short when it comes to voting rights. We’ve forgotten the success story out of Florida years ago. Back when Governor Charlie Crist was in office, from 2007 to 2011, 155,315 offenders had their rights restored. Less than one percent of the re-enfranchised citizens reoffended. It was an unprecedented reduction in recidivism — until the next governor took the rights away.

Voting is collective decision-making; when enfranchised, people see themselves as stakeholders in society, custodians of their communities. So, of course, they’re less likely to break the law.

If voting rights can curb recidivism, then states such as Vermont and Maine, which already allow prisoners to vote, should have rates much lower than other states that permanently disenfranchise people, but they don’t (Vermont houses many inmates out of state, which complicates things).

The reason why “Franchise for all” hasn’t produced the anti-crime effects it promises is that people are confused about whether they can vote. The patchwork of rights across states enables a faulty message that no person with a felony record can cast a ballot. It’s not true. Some can, and some can’t.

And that’s the problem. As many as 17 million people with felony records are eligible to vote but may not know it, so they end up disenfranchising themselves. A study published in Probation Journal found that 68 percent of respondents with criminal records in California didn’t know they were eligible to vote there, which explains why we haven’t seen the public safety payoff to voting rights that we would expect.

Because there isn’t one law on voting rights, an insufficient number of incarcerated people and ex-offenders get the memo that they’re included in society, even in places where they are. Consequently, they miss that boost to self-esteem that being part of the electorate can have on a person.

Misinformation is the enemy here. The way to combat it is to establish one rule on voting, namely that any United States citizen over age 18 can vote, regardless of their conviction history or status as an inmate. The remaining 48 states that don’t allow prisoners to vote should reverse course and agree with Vermont and Maine to not strip anyone of their voting rights. With less confusion will come more voting — and less crime.

We haven’t paid enough attention to the public safety benefits of voting rights for all people, including inmates. Anyone who believes in safe communities as well as second chances should support prisoners’ voting rights.

To find out more about Chandra Bozelko and read features by other Creators writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators website at www.creators.com.