Not A Joke! Retired Justice Kennedy Praises Supreme Court's 'Independence'

Retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy is very concerned about what is happening with the courts, you guys. No, he didn’t have anything to do with it. Why do you ask?

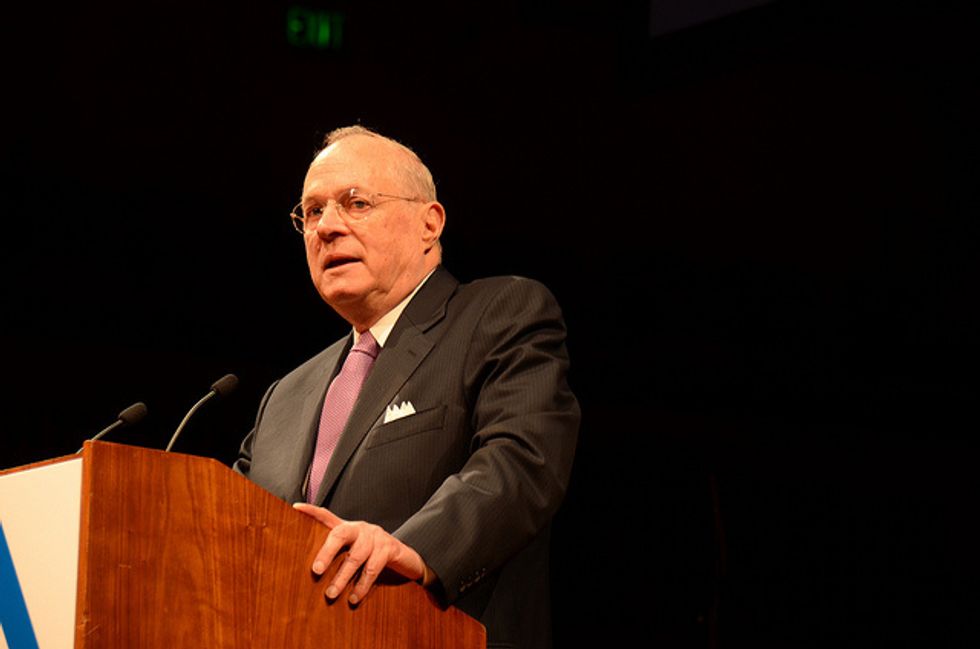

Kennedy’s remarks came during his Thursday speech at a forum titled “Global Risks to the Justice System—A Warning to America.” He was one of several speakers, including judges from countries where authoritarian crackdowns threatened the independence of the judiciary.

The bravery of those judges most definitely did not rub off on Kennedy, who was appointed to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan. In the face of repeated and ongoing attacks on the judiciary by President Donald Trump and his administration, the best Kennedy could do was praise judicial independence, as if that exists on the nation’s highest court any longer.

“Judges decide issues which have political consequences, but they don’t decide in a political way,” Kennedy claimed. “We have to honor the fact that judicial independence does not mean judges are put on the bench so they can do as they like—they're put on the bench so they can do as they must.”

Come on, Tony. Your cute little deal with Donald Trump in 2018, where you personally lobbied him to choose your former clerk Brett Kavanaugh to succeed you, was step two in Trump’s transformation of the court into a conservative grievance machine, following on the heels of Justice Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation the previous year.

You were perfectly aware that opposition to abortion was one of Trump’s litmus tests for Supreme Court nominees—he even campaigned on it. You were also perfectly aware that many of his lower court picks during his first term openly held anti-LGBTQ+ views. Trump explicitly chose judges because they would rule “as they like” instead of ruling “as they must.”

Indeed, when judges do rule as they must, and Donald Trump doesn’t like it, he attacks them personally. He called for Judge James A. Boasberg to be impeached after he blocked the administration from deporting Venezuelan immigrants.

At least 11 judges have had their families threatened with violence after they ruled against the Trump administration. Many of the threats occurred over at Elon Musk’s Nazi bar, X, where Musk himself amplified some of them. High-profile Trump supporter Laura Loomer shared a photo of Judge Boasberg’s daughter, alleging that she was helping undocumented gang members and calling for Boasberg and his daughter to be arrested and his entire family to be deported. James Boasberg was born in California to U.S. citizens, so the deportation demand is equal parts chilling and weird.

U.S. District Judge John Coughenour faced both a bomb threat and a swatting incident after he ruled Trump’s birthright citizenship order was unconstitutional. During his speech, Kennedy fretted that “Judges must have protection for themselves and their families. Our families are often included in threats” without ever acknowledging who is whipping up those threats.

Congressional Republicans have attacked judges on every front. They’ve called for the impeachment of judges who block Trump’s illegal actions. The Senate tried to get a provision in the Big Beautiful Bill restricting lower courts from issuing preliminary injunctions against the government unless the plaintiff posted a bond equal to whatever the government said were its costs and damages from not being able to do illegal things right away.

Whenever conservatives want to both-sides the threats to the judiciary, they have literally one example: At a 2020 rally outside the Supreme Court, Sen. Chuck Schumer called out Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch and said, “You have released the whirlwind, and you will pay the price. You will not know what hit you if you go forward with these awful decisions.” Roberts immediately issued a statement quoting Schumer and saying that “threatening statements of this sort from the highest levels of government are not only inappropriate, they are dangerous.”

But when Trump relentlessly attacks the judiciary, including routinely defying court orders, and elected officials call for judges to be impeached, the best Roberts could come up with was, “For more than two centuries, it has been established that impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision. The normal appellate review process exists for that purpose.”

This is equally as mealy-mouthed as Kennedy’s comments that the judiciary should stand for the rule of law and “we must always say no to tyranny and yes to truth.” Notably absent is any mention of who is attacking the rule of law. Notably absent is any mention that the rule of law went out the window when the conservative majority granted Trump immunity. Notably absent is any mention of who is saying yes to tyranny and no to truth.

Kennedy doesn’t deserve praise or a cookie for these vague statements. If he genuinely cared about attacks on the rule of law, he would need to challenge his former colleagues. He would need to challenge Trump, the man he cut a deal with to get Kavanaugh a lifetime appointment. He would need to say that the threats of violence against judges only occur when they rule against the administration. He would need to call out the ceaseless attempts by GOP elected officials to knee-cap the courts.

Kennedy is not going to do any of those things, but he’s probably going to continue to make a lot of high-minded speeches. Feel free to ignore him until he tells the truth.

Reprinted with permission from Daily Kos.