Stop The Gouging: A Bold Plan To Make American Health Care Truly 'Affordable'

It happened so quickly you might have missed it. In early September, media outlets across the country reported alarming news for everyone on employer-based health insurance plans.

A national survey of 1,700 businesses that offer health insurance to their workers found that 2026 will bring the steepest increases in their medical costs in 15 years—6.7 percent, on top of a six percent rise in 2025. They blame higher hospital and drug prices, greater demand for care, and other factors. According to the consulting firm Mercer, which conducted the survey, much of that burden will be foisted onto employees in the form of higher premiums taken out of their paychecks and higher co-pays and deductibles when hospitalized, seeing a doctor, or filling a prescription.

This pain is hitting at a time when most Americans are struggling financially, and “affordability” is dominating political debate. President Donald Trump’s poll numbers are sinking because voters feel he has betrayed his campaign promise to bring down living costs. Democrats, meanwhile, swept off-year elections by laser-focusing on that vulnerability.

Yet neither party has managed to come up with a plan to address exploding health care costs for the 165 million Americans with employer-provided insurance. During their failed six-week government shutdown, Democrats in Congress put their political chips on a different health care cost crisis: the expiration of the Obamacare tax credits that Republicans refused to extend in their One Big [Ugly] Bill last summer.

Restoring those tax credits is certainly a worthy fight. More than seven million Americans face an average 26 percent increase in their premiums in 2026, according to KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation). Some 5 million will likely drop coverage altogether, unraveling much of the gains made since passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Another eight million will lose Medicaid coverage over the next decade because of cuts to that program in the OBBBA, according to the Congressional Budget Office. As I recently explained in The Washington Monthly, universal coverage is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for addressing the long-term affordability crisis in health care.

But in terms of basic political arithmetic, the failure of both parties to offer voters a specific plan for dealing with rising employer-provided health care costs is hard to fathom. After all, 70 percent of working-age Americans get their health insurance from their employers, compared to 10 percent from Medicaid and under five percent from Obamacare. (The rest are either uninsured or have military or Medicare disability coverage.)

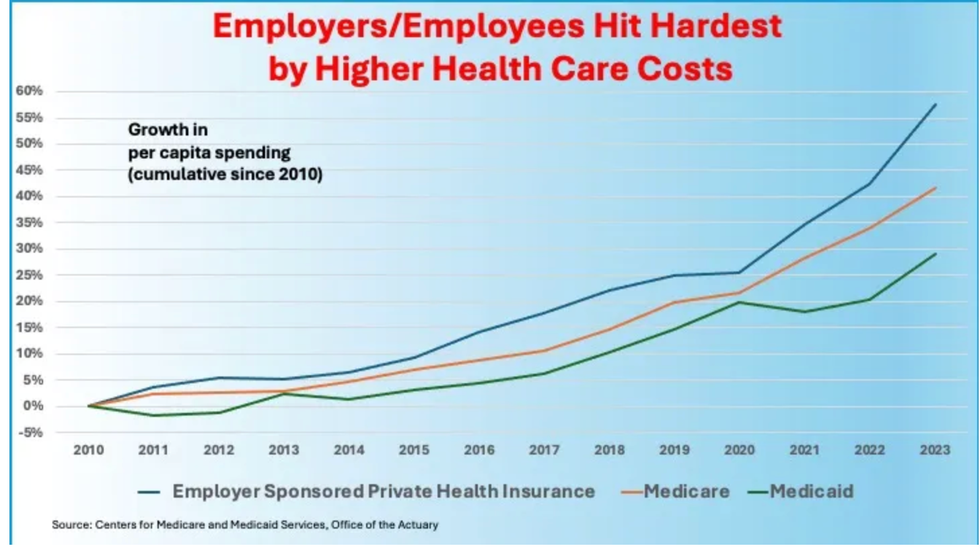

Employer-provided plans not only cover most working-age Americans and their families, but are also where the health care system’s inflation is worst. Thanks to cost control requirements in the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act and other government measures, spending per enrollee in Medicare and Medicaid has risen far more slowly over the last 15 years than in employer-sponsored plans. The latter aren’t subject to such controls and are increasingly vulnerable to price gouging by provider and insurer conglomerates that enjoy geographic monopolies.

The rapid inflation in the prices paid to hospitals, doctors, labs, and other health care providers by employer-sponsored plans also contributes to the slow or stagnant real wage growth that most Americans have experienced for many years. Corporate revenues that might otherwise have gone to raises have instead been spent on the ever-rising costs that employer plans are compelled to absorb.

For a long time, most workers covered by these plans were only dimly aware of how these rising prices affected their standard of living because they rarely had to reach directly into their own pockets to pay them. But that is becoming less true as employers try to offset the ballooning costs by exposing their employees to ever-higher premiums, deductions, co-pays, and co-insurance. In recent years these out-of-pocket costs have on average been speeding ahead at a rate faster than inflation and workers’ wage gains.

Just as rising electric bills turned out to be the sleeper concern of voters in the 2025 off-year elections, so might higher employer-provided health care costs in the 2026 midterms. It would be political malpractice if Democrats did not offer the 165 million Americans with employer-provided coverage real relief from costs that are eating away at their paychecks and standard of living.

A three-part solution

In what follows, I sketch out the basics of a three-part plan that offers a practical and enduring solution to the health care affordability crisis.

First, the plan would place a reasonable cap on the percentage of income any individual or family must pay for health care annually, regardless of whether or how they are insured. This will radically reduce the financial toxicity visited on many insured persons when they get sick, and the scourge of new medical debt heaped on the un- and underinsured.

Second, the plan would require health care providers to charge the same price for the same service, regardless of a patient’s insurance status. This will save the system hundreds of billions of dollars annually by reducing administrative expenses and by bringing down the grossly inflated prices providers charge patients with employer-provided coverage––currently 2.5 times what they charge Medicare.

Finally, the plan would put all hospitals on a budget—a move that would end insurers’ prior authorization schemes and incentivize providers to keep people well and deliver the most effective and efficient care when they get sick.

This three-part reform plan will put the American health care system on a long-term path to controlling overall costs. It will also help employers’ bottom lines and increase the likelihood that more small businesses will be able to offer health insurance to their employees. Best of all, if accompanied by a mandate that employers share a portion of the savings with their employees, it will deliver immediate relief of between $1,500 and $4,000 to the typical working American family—a rebate, if you will, on the excessive health care expenses they have been unwittingly paying. That’s a benefit any self-respecting political candidate ought to be happy to run on.

One bold solution that many left-of-center Democratic candidates competing in next spring’s primaries will likely run on is Medicare for All. But in general elections, that program will run into the same political buzz saw that doomed the effort in Sen. Bernie Sanders’s Vermont, the only state that has tried to create a M4A model. Its Democratic governor concluded the level of taxation necessary to entirely replace employer contributions and reduce individual out-of-pocket expenses was prohibitive. Moreover, a single-payer health care system remains vulnerable to politically charged slogans like “you’ll lose what you have.” Despite the staggering growth in costs, most businesses, unions, and employees want to keep employer-based coverage.

Other Democrats, meanwhile, are already fashioning long lists of health care system changes they hope to enact should they regain Congress and the White House in 2029. Those include curbing provider and insurer consolidation through rigorous application of antitrust law; lowering the Medicare eligibility age to 60; extending the government’s price negotiations to more drugs; prohibiting drug advertising on television; cracking down on pharmacy benefit managers; allowing greater use of physician and nurse assistants; more funding for fighting substance abuse and treating mental health; and more. Few will read this small-bore, incrementalist agenda, and even fewer will understand how it saves them money.

What the Democratic Party and health care reformers need to address directly is affordability, the main issue bedeviling the American people. The reforms needed to achieve affordability must be few in number, easy to understand, and provide real relief. As former Labor Secretary Robert Reich recently noted, people are not persuaded by a “‘10-point plan’ with refundable tax credits that no one understands.”

To that end, I propose that every Democratic candidate looking for a popular, easy-to-sell health care agenda unite around these three simple reforms.

1. A firm cap on all out-of-pocket expenses

All payers, whether private or public, must restructure their health plans so that no individual or family spends more than 8 percent of their annual income on health care. This cap covers all premiums, co-premiums, deductibles, co-pays, and Medicare payroll taxes and Part B premiums. A hard cap will sharply reduce the number of people accruing new medical debt. The medical debt crisis has left at least 20 million adults with either unpaid bills or long-term debts (some estimates are as high as 36 percent of all U.S. households). This forces millions of people into credit card debt, the arms of predatory lenders, or bankruptcy. It forces them to cut back spending, eliminate “frills” like home repairs and family vacations, and skip payments on other bills.

A firm cap on out-of-pocket spending will substantially reduce the unseemly sight of Americans, alone in the developed world, launching GoFundMe pages to pay their medical bills. It will also finally make the U.S. health insurance system fair because it spreads the financing of high-cost patients across all plan members without unduly burdening the sick. This is, after all, what insurance is supposed to be about.

All government programs and the individual market under Obamacare will also be governed by this cap. In the latter case, it will replace its current complicated subsidy formula. There is a precedent for this principle: The Biden administration’s enhanced subsidies for exchange-purchased plans included an 8.5 percent cap on individual premiums.

2. One price for all

America must adopt a single pricing system under which each provider charges all payers the same amount for the same service or product. This will sharply lower prices for private plans, which paid on average 2.5 times more than Medicare and Medicaid in 2022, according to a Rand survey. This in turn will provide substantial premium relief for both employers and workers.

The U.S. is the only country in the world that has an optional private insurance market for the working-age population with no government-mandated mechanism for controlling prices or premiums. (As noted above, those are slated to rise by nearly seven percent next year.) Multiple payers in that private insurance market create multiple prices that are largely determined by the relative market power of providers and insurers, which have been combining into geographic monopolies that extract ever-higher payments from employers.

As a result, U.S. hospitals and physicians’ offices administer the most confusing and expensive billing systems in the world. Some providers have as many as a dozen different prices for the same service: one for traditional Medicare, one for Medicaid, and one for each insurer in their service territory—each of which negotiates different rates for its different plans, including privately managed Medicare Advantage and Medicaid. Then there’s the rack rate for anyone who walks in off the street.

The cost estimates for administering this complex system range into the hundreds of billions of dollars a year. I estimate the administrative savings alone from simplified single-pricing could save employers and employees at least $100 billion a year in reduced premiums.

Prices would instead be determined by a process like the one Medicare has used for decades to set the amount doctors and hospitals receive for treating patients with specific conditions (with individual hospitals having some pricing flexibility as long as they charge all patients the same—see next section). In practice, that would mean raising Medicare and Medicaid rates while dropping commercial rates, thereby creating a single price schedule sufficient to meet the overall financial needs of the system. The exact amount of savings would depend on how much government program prices would have to rise to accommodate the economic needs and political power of providers. But the savings to employers and covered employees would be enormous, likely reducing premiums by hundreds of billions of dollars annually in addition to the $100 billion in administrative savings.

Another benefit of single pricing is transparency for consumers. Not many medical services are shoppable. No one experiencing what they think is a heart attack rushes to their computer before the ambulance arrives to find out who has the cheapest ER prices. Indeed, a recent study by the Health Care Cost Institute estimated that only 12 percent of 2017 medical expenditures, excluding prescription drugs, were either delayable or discretionary, and thus shoppable.

But greater competition in this limited set of services can help keep prices down. Unfortunately, current transparency laws have proven largely unworkable for consumers hoping to shop around for the cheapest alternative for, say, an MRI scan on that troublesome knee, or a routine colonoscopy. Most providers, given the multiple prices they must post, have created disclosure websites that are about as easy to navigate as a health insurance policy. Requiring every provider to list a single price, especially if linked to the federal government’s existing quality ratings, will foster competition previously unknown in the health care sector.

Finally, single pricing will remove the single biggest roadblock to Medicaid patients finding providers willing to take their insurance. The Medicaid Payment Advisory Commission estimates only 70 percent of physicians are willing to take new Medicaid patients compared to more than 95 percent who welcome new Medicare patients. Why? Low Medicaid prices. If every provider has to charge every payer the same price, this problem largely goes away except in many rural or economically depressed areas where everyone faces a provider shortage.

3. Put providers on a budget

Serious problems can arise after moving to a single-price system, as Maryland, the only state that has one, discovered over a decade ago. Hospitals there began to game the system by increasing unnecessary surgeries, tests, and procedures.

Maryland’s solution was to require that hospitals and hospital systems, which collect a third of all health care spending, adhere to an annual budget no matter what price they set on individual services. The state’s regulator, the Health Services Cost Review Commission, also sets limits on how much those budgets can grow each year after accounting for changes in demographics, best practices, and technology. Providers are guaranteed their annual budgets. If an individual service is used more or less than anticipated, the price for that service can be adjusted up or down for all patients, but hospitals may not exceed their budgets.

Requiring providers to adopt these so-called “global” budgets that grow more slowly than the rest of the economy creates a financial incentive for eliminating wasteful care, and frees up resources to boost primary and preventative care. Hospitals on a budget earn more money if they don’t have to provide as much care for the sick, meaning that they’re incentivized to keep people healthy while generating the best health outcomes at the lowest possible price for their patients when they do get sic

Yet neither party has managed to come up with a plan to address exploding health care costs for the 165 million Americans with employer-provided insurance. During their failed six-week government shutdown, Democrats in Congress put their political chips on a different health care cost crisis: the expiration of the Obamacare tax credits that Republicans refused to extend in their One Big [Ugly] Bill last summer.

Restoring those tax credits is certainly a worthy fight. More than seven million Americans face an average 26 percent increase in their premiums in 2026, according to KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation). Some five million will likely drop coverage altogether, unraveling much of the gains made since passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Another 8 million will lose Medicaid coverage over the next decade because of cuts to that program in the OBBBA, according to the Congressional Budget Office. As I recently explained in the Washington Monthly, universal coverage is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for addressing the long-term affordability crisis in health care.

But in terms of basic political arithmetic, the failure of both parties to offer voters a specific plan for dealing with rising employer-provided health care costs is hard to fathom. After all, 70 percent of working-age Americans get their health insurance from their employers, compared to 10 percent from Medicaid and under 5 percent from Obamacare. (The rest are either uninsured or have military or Medicare disability coverage.)

Tax Reform Is Key

These three reforms work best if adopted in tandem. Each cannot succeed on its own. But if adopted together as part of new federal legislation, these reforms could put the U.S. health care system on a glidepath to financial sustainability.

Making them work will require significant federal expenditures. How much, and how to pay for it, is a difficult but solvable question.

Phillip Longman, senior editor at the Washington Monthly, has long argued for a single- price system that would reduce what self-insured businesses and private insurers pay by 60 percent, matching the prices that Medicare currently pays. If this were possible, no federal funds would be needed to finance a single price system. Alas, I don’t believe it is possible.

Though it’s true that many hospitals and physicians serving mostly working-age and Medicare-covered patients are financially stable and offer excellent care, those serving less healthy patients in low-income areas––so-called “safety-net” hospitals—are frequently on the brink of bankruptcy. Survival for many depends on the additional monies brought in by their relatively few well-insured patients and federal subsidies. It would be a disaster for these providers if rates paid by privately insured patients dropped to current Medicare rates.

Hospitals in well-off areas, meanwhile, feast off the higher payments extracted from their well-insured clientele. That’s where the fat in the system is. But lowering their prices to existing Medicare rates would deliver an immediate financial shock to existing operations, generating tremendous pushback from local hospital leaders, physicians, and their elected representatives, regardless of party.

To make a single-price system work economically and politically, then, Medicare payment rates to providers will also need to rise. How much? By 60 percent, I would estimate, based on a real-world test case. When Democratic leaders in Washington offered a publicly funded option on that state’s Obamacare exchange, provider organizations successfully lobbied for payment rates that were 160 percent of Medicare rates––still lower than existing commercial rates, but well above the government program’s rates. They convincingly argued that many hospitals and doctors’ offices could not survive without the cross-subsidization provided by the sky-high prices paid by employer-provided plans.

A single pricing system that made a similar average rate cut for private payers would save employers and their employees, according to my own rough estimate, more than $400 billion a year. That works out to a $1,200 a year reduction in annual premiums for the average working family, or a total of $1,500 a year when administrative savings are added in (presuming employers are mandated to share the savings with their employees).

The problem, of course, is how to finance that extra $400 billion, which will now be coming from the federal government. The obvious fix would be to recapture the $400 billion in employer savings by raising their Medicare taxes by an equal amount (while not raising such taxes on employees).

Financing single pricing in this way will have the additional benefit of boosting manufacturing in the U.S. by making the health care cost burden between firms more progressive. Old-line firms like General Motors, Caterpillar, and John Deere pay the highest premiums because their workforces are older, sicker, and middle-income. Meanwhile, the highly profitable tech titans that now dominate the U.S. economy like Apple, Meta, and Google have workers who are younger, healthier, and better paid. They spend far less per worker for health insurance. Tripling the employer Medicare payroll tax will have the beneficial effect of lowering total health care costs for those firms with older, sicker workforces while raising costs for those businesses with younger, healthier ones.

For this reason, old-line firms with older workers would have good reason to provide crucial political support for the plan. We can also expect, however, well-funded and intense pushback from other corporate sectors that would face sharp payroll tax increases. Their opposition, plus resistance from providers, will make reform a tough road.

But there’s no law saying that the only way to fill the $400 billion gap is by raising Medicare taxes. Other forms of federal revenue would work. Lawmakers could, for instance, tax things that make people less healthy: air pollutants, sugar-laden foods, or other detrimental products. Alternatively, they could pay for the plan by raising tax rates on corporate and top earners—moves that voters overwhelmingly favor. Indeed, much of the plan could be financed merely by closing the insane new loopholes (such as gutting the alternative minimum tax) that the Trump administration is creating for major corporations and wealthy individuals above and beyond the OBBBA.

This would be a huge net advantage to the vast majority of employers, who would be relieved of a significant share of their health care liabilities with no requirement that they pay higher Medicare payroll taxes. And Democrats could mandate that an appropriate portion of that money be rebated to employees in the form of higher pay. In 2024, the total estimated cost to a typical family of four in an employer-provided health plan was around $27,000, according to KFF. If such a family received a 25 percent share of the savings from these reforms, its pretax income would increase by around $4,000.

To win back working- and middle-class voters who already trust them more than Republicans to do the right thing on health care, Democrats need to offer a plan that immediately limits workers’ out-of-pocket costs. For employers, unions, and others who want to “keep what they have,” single pricing tied to annual budgets preserves the employer-based system while providing them with the long-term benefit of slower- growing costs. For the millions of small businesses that don’t currently provide coverage, the plan will make it much cheaper to do so. Such a plan might even win support from the few GOP officials willing to free themselves from the fear-driven grip of Trump’s faux populism.

This article first appeared on The Washington Monthly website.

Merrill Goozner, the former editor of Modern Healthcare, writes about health care and politics at GoozNews.substack.com, where this column first appeared. Please consider subscribing to support his work.

Reprinted with permission from Gooz News

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation