Reprinted with permission from Alternet

We can stop waiting for the big constitutional crisis, the cataclysmic electoral breakdown, the fracturing of democracy that many have long feared in the United States of America.

The crisis is already here, and we've been living with it for years.

It's become conventional wisdom among many political observers that the Electoral College system for picking our presidents is an anti-democratic relic that we're nevertheless forced to work around. And yet the significance of this fact is far too easily elided. We hear warnings that the Electoral College may one day trigger a disaster, but we've yet to properly take stock of the world of crisis we've already made for ourselves. And American political discourse still hasn't accommodated the fact that, because of the Electoral College and the winner-take-all state rules that decide our presidential elections, our form of government is not as democratic and morally admirable as we like to think.

Within the last two decades, there have indeed been, arguably, four distinct crises in the Electoral College that have profoundly shaken our democratic ideals and even warped the course of world history. Lives have been lost and ruined; blood has been shed as a result. The Electoral College is not just an outdated institution. It's a shambolic mess. The wheels have completely come off, and the train is off the tracks. And there's no sign it's headed for any smoother terrain.

The first of the modern crises, of course, came in 2000. The presidential election came down to Florida, and that state came down to 537 votes. A wave of irregularities and clear errors in the process easily swamped that margin, but as the fight over a recount dragged on, the Supreme Court was asked to intervene. Its decision essentially gave George W. Bush the presidency over then-Vice President Al Gore, despite the fact that Gore had won nationally by about half a million votes.

Gore conceded graciously, but a disaster was set in motion. The 9/11 Commission cited the delayed transition as a potential factor in the failure to foresee the coming terrorist attack mere months down the road. Had the Clinton administration smoothly transitioned into a Gore administration as most American voters wanted, perhaps that calamity could have been avoided — along with the disastrous wars of choice that followed. The country might have started taking climate change seriously at a crucial point in history, rather than ignoring it for far too long. The legitimacy of the 2000 election's outcome has never been broadly accepted, as many Democrats were outraged that the Supreme Court had sided with Bush and resented a system that let a contested 537 votes hold more sway than the hundreds of thousands more Gore could boast in his total.

And it wasn't just Democrats who could see the problem with the Electoral College's structure outweighing the collective voice of the voters. Contemporary news reports suggested that if, as had seemed possible before the election, Bush had won the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College, his team would have fought fiercely in favor of letting the popular vote control. They would have argued for the plausible view: For the only two nationally elected officers — the president and vice president — the nation's vote as a whole should be what matters.

But as we all know, that's not how the world works.

"There is no constitutional right to vote for the president," Jesse Wegman, a member of the New York Times editorial board and author of the book, "Let the People Pick the President: The Case for Abolishing the Electoral College," told me. "You and I and every other citizen have no right at all to play a role in choosing the president. It's just the state legislators' decision to let us do that."

In the American system, state legislators wield enormous power, though they tend to attract much less attention than the U.S. Congress. Under the Constitution, they get to decide how electors are selected every four years to join the Electoral College, which then gets to pick the president and the vice president. Because most states have elections with winner-take-all rules, giving all of the state's electors to a single candidate, it's possible for the winner of the national popular vote to fail to win a majority of the Electoral College votes.

After the 2000 election highlighted this glaring flaw, many demanded change. But amending the Constitution to reform or abolish the Electoral College is extremely difficult because the people who benefit from the current system have the power to veto any reform. And the unique circumstances of the 2000 election — such a narrow margin in Florida, and botch election administration that included hanging chads and butterfly ballots — could almost be dismissed as a fluke.

And then it happened again.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton decisively won the popular vote. She won by more than 2 points and nearly 3 million votes. But despite winning 48.2 percent of the vote, she lost in the Electoral College to Donald Trump, who won a mere 46.1 percent of the vote.

That, on its own, should've been considered a crisis. Once again, the candidate with much more support from the voters was denied the presidency in favor of her less popular — not to mention clearly unfit — opponent. But Clinton herself avoided such language, conceding graciously the day after the election.

Those were the rules of the game, of course, and Clinton and Trump knew that going in. Had the results been reversed, Clinton would have happily taken office while losing the popular vote. But that doesn't mean the result was acceptable or right. The fact that we don't set up any other important election to function in this way shows that this arrangement doesn't have any intuitive appeal or inherent moral legitimacy. It's just what we've come to accept. Wegman persuasively argues that it wasn't an ingenious solution developed by the American Founders, either — it was a last-minute agreement by deeply flawed men that no one was ever really satisfied with.

Because Clinton was widely expected to win in 2016, and Trump was such an outlandish character, much of the media coverage in the days after the election focused on the fact of the stunning upset. Many urged Democrats and Clinton supporters to re-evaluate their own assumptions about the electorate and to question why the country had found Trump so appealing.

But the country hadn't found Trump so appealing. Millions more voted for his opponent. The odd quirk about the Electoral College, though, is that despite the fact that everyone knows it doesn't adhere to our traditional assumptions about democracy, the political establishment implicitly assumed there's something inherently just about the winner's claim to office and that they represent the will of the voters.

Trump didn't represent the will of the voters, though, as the numbers made clear. For a second time since 2000, democracy failed for the single most important office in the country. And this failure was massively consequential. The winner picked three Supreme Court justices, completely reshaping the balance of the court. He rewrote the tax code, started trade wars, defied Congress, tormented immigrants, ordered assassinations and executions, manipulated the tools of justice. And he oversaw mass death and misery during the COVID-19 pandemic as public experts pleaded with him to stop lying and do more to stop the virus.

His foreseeably catastrophic and plutocratic presidency was forced upon the country and the world, even though a majority of Americans thoroughly rejected him and more voters cast their ballots for his opponent.

American democracy broke down, and it hasn't yet been fixed. Some people tried to implement a last-ditch solution in 2016 to his unjust rise, after all the votes were cast, as Wegman recounts in "Let the People Pick the President." A group of faithless electors tried to break with the expectation that they cast their votes in line with their states in an effort to deny Trump the presidency.

It didn't work, of course. Only seven electors voted out of turn — five from Clinton and two from Trump. It was nowhere near the number that would've been required to deny Trump the presidency.

But it was, on its own, a mini-crisis of democracy. It was a serious effort to undo the outcome that had been set in motion on Election Day. It was itself a response to an emergency, an attempt to set right a grave wrong. But had the effort been successful, it could have unleashed unprecedented chaos, and it's far from clear that would have been a preferable outcome.

When Trump tried to overturn the results of the 2020 election, some pointed to the 2016 faithless electors plan — which wasn't supported by Clinton, who had conceded — as evidence that the Democrats were hypocrites and had been just as unwilling to accept the verdict of the voters.

There are, however, two key differences in the faithless electors' plan and Trump's efforts to undo the 2020 election. First, the faithless electors' plan is actually in accordance with the constitutional design of the Electoral College — it says nothing about electors being pledged to certain candidates. The electors could argue that becoming faithless to block Trump's win was both in accord with the original vision for the Electoral College and an appropriately democratic representation of an electorate who had rejected him. This is the second key difference with the 2020 crisis: the faithless electors were trying to stop a person who had clearly lost the popular vote from taking office.

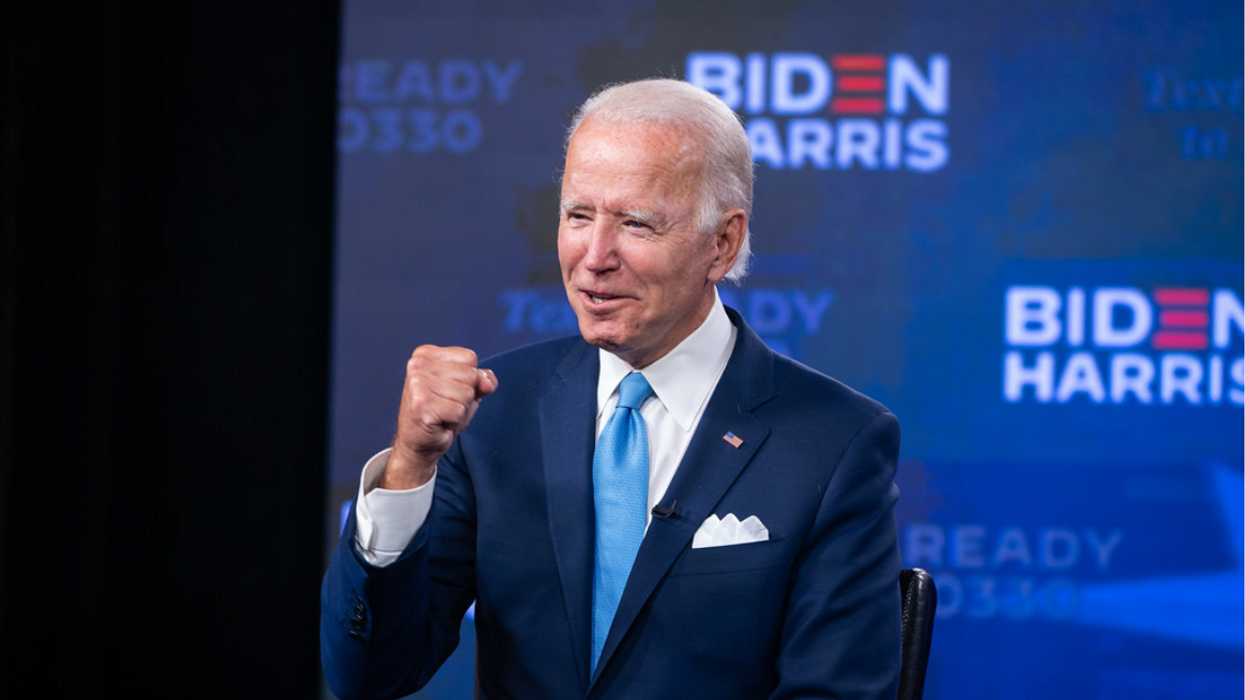

When Trump tried to overturn the 2020 election, he was doing the opposite. He was trying to stop Joe Biden — who not only won the popular vote but a substantial majority of American voters — from rightfully becoming president.

The crisis Trump triggered was not just a crisis of democracy, but a revolt against democracy. By pushing to have state legislatures overturn the result of the election procedures they had already put in place, and pressuring election officials to reject the proper results of those procedures, Trump undermined the bedrock of electoral governance. It was a rejection of the principles of democratic progress and an effort to install autocratic rule.

"It was outrageous that Trump and his allies were trying to do this," Wegman told me. "First of all, the election had already happened. Second of all, there was literally no evidence of fraud or irregularities at all, let alone on the level that they were claiming there was. So there was nothing to overturn."

He added that though it was "terrifying," the events were also "clarifying and illuminating" for the country. "Because it let the American people see just how contingent this whole process is on the state legislatures playing along."

He continued: "And while it was absurd and anti-democratic to try to force their hand after Nov. 3, in fact, at any point before then, the Constitution gave them free rein to change their rules about awarding electors. They didn't have to do it the way they did, which was a popular vote in their state. That's how every state does it, and that's how every state had done it since 1876, but they don't have to. They could change it in a day if they wanted to. And they could change it and say 'We're going to decide for ourselves.'"

Trump took it even further than that, of course. After his gambit with state legislatures failed, he tried to convince his vice president, Mike Pence, to intervene in Congress's counting of the Electoral College vote. Pence refused, and Trump, in response, sent a riotous mob after him and the nation's lawmakers. The violence was a predictable outcome of Trump's rejection of democracy and his cult-like following. Perhaps such an attack would have occurred even if the former president had lost under a pure national popular vote system, but the baroque nature of the existing process created many more opportunities for mischief that someone like Trump would be desperate to exploit. That gave his supporters hope he could remain in office if they just pushed hard enough.

At the same time, the Supreme Court is poised to give state legislatures even more power in setting the terms of elections, unconstrained by popular referendums or courts.

And even though Biden won the election, and Trump's efforts to overturn the outcome failed, he came much closer to winning than he should have.

David Shor, a data scientist for the progressive group Open Labs, which works on progressive causes, stressed how bad the skew of the Electoral College has become for Democrats.

"We got 52.2 percent, and if we had gotten 52 percent, we might have lost," he told me, referring to Biden's share of the two-party vote. "That's what the breakeven point was. The bias of the Electoral College went up. I think a lot of people forecast that it would go down. So that's bad. I think that's really bad. I think it's really under-remarked about."

He continued: "And it makes me think we're probably favored to lose in 2024. We barely scraped 52.2 against the most unpopular Republican incumbent to run in decades. And we still barely scraped by, so I think it's quite bad."

It's been a difficult truth for the media coverage to capture. On the one hand, Biden's Electoral College victory and his national popular vote share were substantial, so his win can be regarded as giving him a significant mandate and a rebuke of his predecessor. But the collective margins of victory in the decisive states that made Biden the winner are actually quite small, less the 50,000 votes. So it's not hard to imagine a very similar world where Trump had legally held on to power — even though he oversaw a world-historical disaster that made an overwhelming and record-setting 81 million voters turn out against him.

But because Trump's efforts to change the rules after Election Day and throw out votes was so outrageous, shameful, and potentially criminal, much less attention was paid to the institution that allowed it to happen at all.

In the wake of Trump's threat to democracy, some observers have boasted that the country's institutions held firm against the threat of autocracy, as they were designed to. But the Electoral College, a central pillar of our constitutional order — didn't protect us — it exacerbated the threat and made it possible to begin with.

Trump never had a hope of flipping any of the states that voted against him after the 2020 election — the margins were just too wide, unlike Florida in 2000. But even this hopeless and corrupt effort rested on a premise that should never be accepted in the first place — that it would be acceptable for Trump to hold on to the presidency even if he lost nationally by 7 million votes.

Wegman argued that there might nevertheless be an upside to Trump's post-election crisis.

"I actually hope it pushes us further in the direction of reforming what is so clearly a system that is not built for the 21st century and Americans' expectations of what it means to live in a modern democracy," he said.

In "Let the People Pick the President," Wegman endorses the idea of the National Popular Vote Compact. Under this scheme, already adopted by many legislatures in blue states, states agree to give their Electoral College votes to the winner of the national popular vote as long as enough other states representing 270 electors have agreed to do so, too. Democratic Rep. Jamie Raskin, recently famous for his role as the lead impeachment manager in Trump's Senate trial, introduced the legislation in 2007 as a state lawmaker that allowed Maryland to become the first to adopt the compact.

It's a clever pathway to get around most of the problems with the Electoral College without needing to pass a constitutional amendment on the matter, which is widely regarded as politically impossible. The hope is that, if it were ever in effect, Americans would get used to the process and the right to pick the president by popular vote, so amending the Constitution to make it permanent would become feasible.

Getting there, though, is the tricky part. Republicans in state legislatures resist the idea because they're aware that their party currently benefits from the Electoral College. And swing states — which, by definition, are necessary to reach 270 electors — have the strongest incentives to keep the current systems in place because they benefit from it enormously.

Wegman suggested that red state legislatures who see their states trending Democratic in the future might be persuaded to adopt the popular vote compact. The winner-take-all system would, if the opposite party takes control, completely nullify any Republican votes for president in their state. So they may see the compact as a way to preserve their relevance and protect their voices.

But Shor is not so optimistic about the national vote compact, calling the plan a "dead end."

"You can only get solidly blue states to pass this thing," he said. "And we're not going to have trifectas in Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin, or Michigan, or any of these other places."

Shor said one plan that helps the Democratic position a bit would be making Puerto Rico a state — a change many have called for on separate grounds. He estimated that adding the island as a state "would erase something like 10 percent of the Electoral College bias." (D.C. statehood, on the other hand, makes no difference in the Electoral College, since it already selects electors.)

In his work, Shor spends more time thinking about how Democrats can cope with the structural bias against them, rather than whether the problem can be fixed. His main answer is that Democrats have to hone their messages to compensate for the game being rigged against them.

"The source of this Electoral College bias as it exists is that as education polarization goes up, generally speaking, that leads to a lot of wasted votes," he said. "Roughly speaking, who does well in these large midwestern states determines the presidency. As those places trend more Republican, unless we do better and reverse education polarization, it's unlikely to go away any time soon."

Basically, the problem for Democrats is that white people without college degrees — who are increasingly favoring Republicans — are overrepresented in swing states.

"We have to turn around and try to appeal to voters in these states that matter more. Which really sucks," he said. "We just have to care more about what midwestern white people think."

Of course, the fundamental idea in a democracy should be that nobody's vote counts more than anyone else's. That's the egalitarian commitment that underlies the system and gives it moral and popular legitimacy. The Electoral College as it's currently set up undermines all that — it says that the rational thing for politicians to do is to care more about certain voters than others, just as Shor advises.

That's the crisis we're living with. And it could easily get worse. Not only is the institution that picks the presidency skewed against the popular will, one of the two major parties is increasingly authoritarian and opposed to democracy. And now, Trump has blazed a path for future challenges to election results, even if has failed.

"Now the sharks are circling, because now they know there's blood in the water," said Wegman. "The party that refuses to try to appeal to more people in a representative democracy has only one way to power, and that's through the manipulation of existing mechanisms to entrench minority rule. And that will kill American democracy. And that will kill the republic."

The GOP has been working hard at this for years. While it's widely known that Republicans heavily gerrymandered congressional districts to their advantage in 2010, Shor argued that even more significant is what happened to state legislatures — the bodies with the ultimate authority over how we pick the president.

"I think this is one of the most under-remarked things in politics," Shor said. "State legislative lines are substantially more gerrymandered than congressional ones. They have more districts to work with. People's intuitions on this are totally wrong. The more districts you have, the easier it is."

With Republicans in control of many key state legislatures, gerrymandering in Republicans' favor is likely going to get worse as we head into another round of redistricting. That means the people who control elections, including the Electoral College, will likely become even more disconnected from the voters and even more extreme. This week, the Arizona legislature even considered a proposal that could potentially let it override the way its people vote in a presidential election, if the legislators so chose.

What's most remarkable to me is that throughout all these crises, the leadership of the Democratic Party seems to lack all urgency. There's certainly a time for calm, stately leadership. But Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and Biden have rarely made the point that there is something fundamentally broken in American democracy. That encourages the media to treat the grossly skewed system of the Electoral College, which keeps throwing the country into chaos and corrupting politicians' incentives, as an acceptable part of the country. And the lulls the public into thinking this is just the way things are, and we have to learn to live with it.

At least until the next crisis.