As Growth Slows, That AI Bubble Just May Burst Into Recession

Gross Domestic Product grew at a 1.2 percent annual rate in the first half of the year, that is down sharply from its 2.5 percent rate in 2024. It is not hard to identify the culprits: uncertainty created by Trump’s tariff threats, the loss of workers due to mass deportation, and government cutbacks in a wide range of areas. This mix is likely to keep us on a path of weak growth through the rest of the year and into 2026, unless the stock market crashes, in which case we could fall into a full-fledged recession.

The weaker GDP growth is matched by weaker job growth. The average of 38,000 a month since April was low enough to get the BLS commissioner fired. That figure likely understates the underlying trend, but probably not by much. The pace of job growth going forward will probably be in the range of 50,000 to 70,000 a month, down from an average of 170,000 jobs a month in 2024.

To a large extent, this slower job growth is by design. The Trump administration’s immigration policy has further reduced the flow of immigrant workers into the labor force (Biden had already sharply reduced immigration in June of 2024) and likely caused many immigrants previously in the workforce to either leave the country or quit their jobs. With the baby boom cohorts retiring in large numbers, the number of native-born workers in the labor force is growing very slowly.

Slower job growth means slower growth in total wages, which in turn means weaker consumption growth. If the labor grows at a rate of 0.4 percent annually (roughly 60,000 a month), that would mean that total wage income is growing 0.4 percent, before adding in real wage growth.

It appears that nominal wage growth is slowing, at least modestly. The annual rate of wage growth during the last three months (May, June, July) compared with the prior three months (February, March, April) is 3.7 percent. Wage growth had been running at 4.0 percent rate in 2023 and 2024.

It slowed even more in the leisure and hospitality sector, which is most sensitive to the strength of the labor market. The average hourly wage for non-supervisory workers in this sector rose at just a 2.5 percent annual rate, comparing the last three months with the prior three months.

There is other evidence of a weakening labor market, notably low hire and quit rates. Also, the unemployment rate for Black and young workers has risen sharply in recent months. These groups typically feel the effects of a slowdown first.

This could mean that we will see further slowing in the pace of nominal wage growth. With inflation rising due to tariffs, real wage growth could slow to a trickle. In that case, consumption growth may be even slower in the second half of 2025 and 2026 than the 1.0 percent rate for the first half of this year.

There is not much to offset the prospect of weak consumption growth. Investment grew at a 6.1 percent annual rate in first half of the year, but it looks likely to slow in the second half. Structure investment is sharply negative, as the boom in factory construction is trailing off and investment in hotels is also slowing sharply. Equipment investment may still grow, but not especially rapidly. Investment in intellectual products is growing but this is due to strong AI driven software investment outweighing weakness in pharmaceuticals and cultural products.

Residential construction fell in both of the last two quarters. It may stabilize, but it is unlikely there will be any major turnarounds absent some big change in policy.

The government sector shrank slightly in the first half of the year, driven by cutbacks in federal spending. State and local spending is likely to weaken in the second half of 2025, as less federal money forces cutbacks. Trade will at best be a small positive factor. Fewer goods imports will mean a modest boost to domestic production, but we are also likely to see a decline in goods exports, as well as exports of services, like foreign tourism in the United States.

The overall picture is one where the economy is barely growing. Unemployment may stay low in spite of weak job growth, due to slow growth in the size of the labor force. However, workers will not feel confident in their labor market prospects and therefore unable to push for healthy wage gains to offset Trump’s tariff hikes. That is not a recession story, but one where we may not be very far from one.

What If the Stock Bubble Bursts?

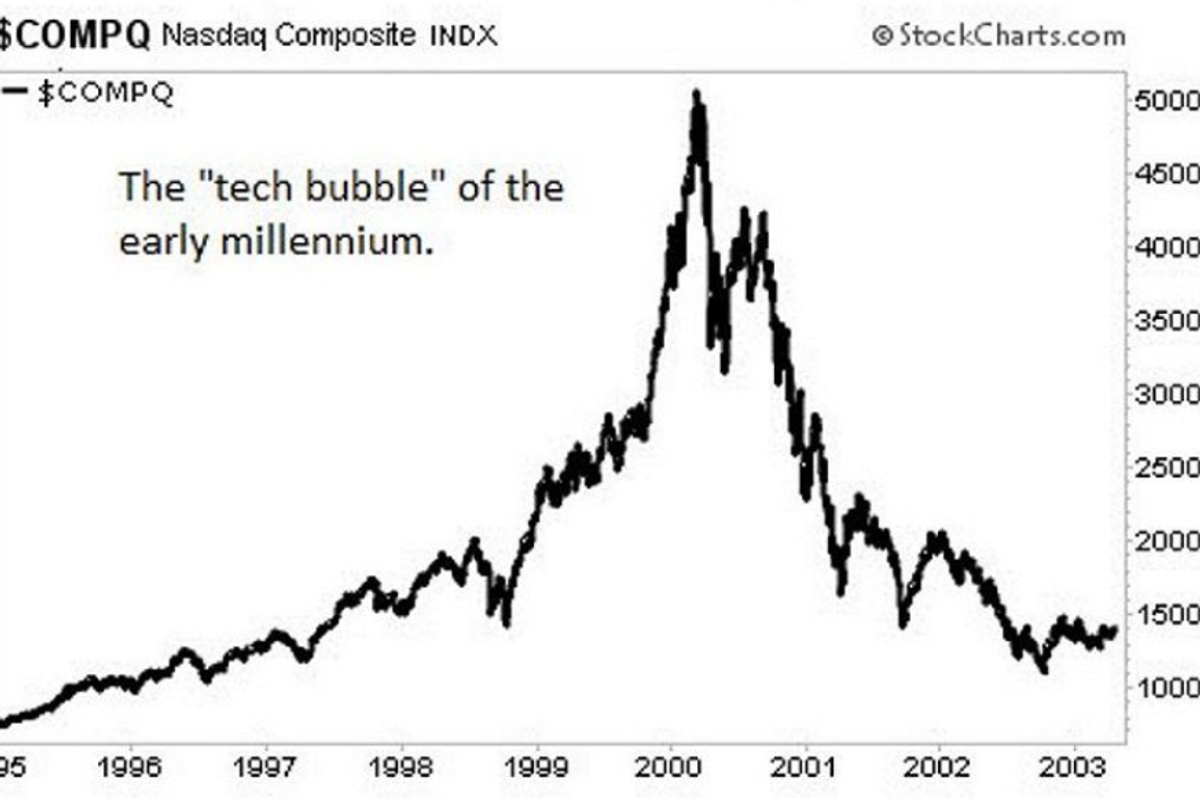

That’s the positive story for 2025 and 2026, but suppose the AI driven stock bubble bursts? As many commentators have pointed out, the stock market today is starting to look a lot like it did in the late 1990s bubble, which peaked in March of 2000. It eventually plummeted with the S&P losing close to half its value by the summer of 2002.

It’s worth noting that it was not just the tech stocks that plummeted in the 2000-2002 crash. Even the stock of long-established companies like McDonalds and GM lost close to half of their value.

I am not going to try to guess the timing of a crash. I was closely following the stock bubble in the late 1990s, as well as the housing bubble in the 00s. Both bubbles lasted far longer than I would have thought possible. Big money types are able to pursue illusions for a long time, and in the case of the housing bubble, commit outright fraud in the form of mass securitization of loans they knew to be bad.

Perhaps the event will be the recognition that China seems to be well ahead of us in developing AI in important ways. It is also worth noting that the leading Chinese companies seem to have systems that use an order of magnitude less electricity in a country where it is half the cost and far more plentiful. With recent actions by the Trump administration to nix clean energy, the availability of ample low-cost electricity is likely to give Chinese AI developers a major advantage.

Anyhow, who knows what could tick off a collapse of the AI driven bubble. Even a quarter century after the fact, it would be hard to identify an event in March of 2000 that suddenly warranted an end to the Internet bubble. It is easy to speculate on the consequences. Needless to say, the boom in investment in AI would end quickly, as would the rush to build power plants to serve the electricity needs of AI.

While the size of a decline is also hard to predict, even a drop of just 15 percent would eliminate $10 trillion in stock wealth. That would be a big hit to consumption, knocking down annual consumption by as much as $300-$400 billion, which would be virtually certain to throw us into a recession. And considerably larger declines are not out of the question.

It is difficult to know all the knock-on effects of a collapse of an AI bubble. Perhaps crypto will take a huge hit as well. Maybe we will find some major financial institutions were doing very foolish things, as turned out to be the case with the Silicon Valley Bank in the spring of 2023. In any case, a recession is a far safer call if the AI bubble collapses. For now, look for a future of weak economic growth and very weak real wage and consumption growth.

Dean Baker is an economist, author, and co-founder of the Center for Economic Policy and Research. His writing has appeared in many major publications, including The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and The Financial Times.

Reprinted with permission from Substack.

- The Limits Of AI: That Expensive And Power-Hungry Tech 'Miracle' - National Memo ›

- Trump 's Economy Is Losing Jobs, So He Wants A New Scorekeeper - National Memo ›

- Bursting The AI Bubble Just Might Be Better For (Almost) Everyone - National Memo ›

- Trump's Weak Economy Grew 1.5 Percent In First Half Of 2025 - National Memo ›

- AI Bubble Drives Up Prices, Harms The Environment And Deserves To Burst - National Memo ›

- How Criminals' Most Favored Currency Became A 'Trump Trade' - National Memo ›

- - National Memo ›

- Warning: Here's Why The Fed Can't Rescue Markets From AI Bubble - National Memo ›