By Dan Whitcomb

The social costs stemming from dangerous levels of lead in the drinking water of Flint, Michigan, such as the effect on children’s health, amount to $395 million, according to an analysis by a professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

The total takes into account some 8,000 children believed exposed to lead poisoning in Flint since April 2014, when the financially struggling city, under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager, switched its water source from Detroit’s municipal system to the Flint River to save money.

The river water was more corrosive than the Detroit system’s and caused more lead to leach from Flint’s aging pipes. Lead can be toxic and children are especially vulnerable. The city switched back last October.

The crisis has prompted lawsuits by parents in Flint, which has a population of about 100,000, who say their children have shown dangerously high levels of lead in their blood.

The study calculated the lifetime economic losses expected to be suffered for every exposed child. The U.S. lead health standard has been lowered repeatedly since the 1960s, but according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention no safe level has been identified.

“We should never ignore the human costs of lead poisoning,” study author Peter Muennig, an associate professor at the university, said in a statement released with his analysis, published in a letter to the journal Health Affairs.

“Even relatively low levels of exposure may rob children of IQ points and predispose them to violent behavior later in life,” Muennig said.

Overall societal costs of all low-level lead exposures in the United States – measured as lost economic productivity, welfare use and criminal justice system costs – was over $4.5 billion last year, according to the study.

In July six state employees in Michigan were criminally charged in connection with the case. Some critics have called for high-ranking state officials, including Governor Rick Snyder, to be charged. Snyder said in April he believed he had not done anything criminally wrong.

(Reporting by Dan Whitcomb; Editing by Leslie Adler)

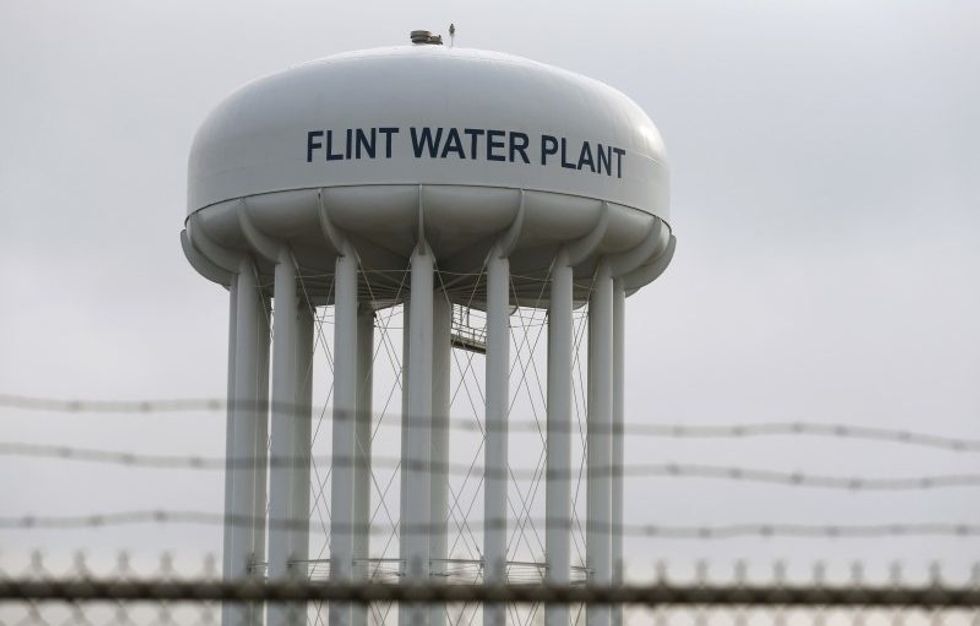

Photo: The top of the Flint Water Plant tower is seen in Flint, Michigan February 7, 2016. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook/Files