Federal Reserve's Rate Cut Won't Do Harm, But Its Next Chair May Be Ruinous

Kevin Hassett

Yesterday the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds rate — the interest rate on overnight loans between banks, which the Fed effectively controls — by a quarter point. There are four things you should know about that cut:

· Although Donald Trump has been screaming at the Fed, demanding big rate cuts, there isn’t actually a compelling case for cuts right now

· On the other hand, this cut is unlikely to do any harm

· In fact, Fed policy over the next few months barely matters

· The important questions now are political: Will Trump destroy the Fed’s independence, and do to monetary policy what he has done to health policy — put it in the hands of charlatans and cranks?

Why do I say that there isn’t a compelling case for a rate cut? The Fed has a “dual mandate”: It’s supposed to seek both price stability and full employment. To fulfil this mandate as best it can, the Fed normally cuts interest rates when the job market is weak, raises rates when inflation is running hot.

Right now, however, the job market and the inflation rate are giving conflicting signals. Unemployment is somewhat elevated — 4.4 percent compared with an average of four percent last year — and other indicators, like the time it takes workers to find jobs, are showing weakness. On the other hand, inflation is running at around three percent, above the Fed’s target of two percent. So you can make the case either for or against yesterday’s cut.

Indeed, the Fed’s official statement about the interest rate decision highlighted the ambiguity, noting the risks on both sides and justifying its move with a guarded reference to rising “downside risks to employment.”

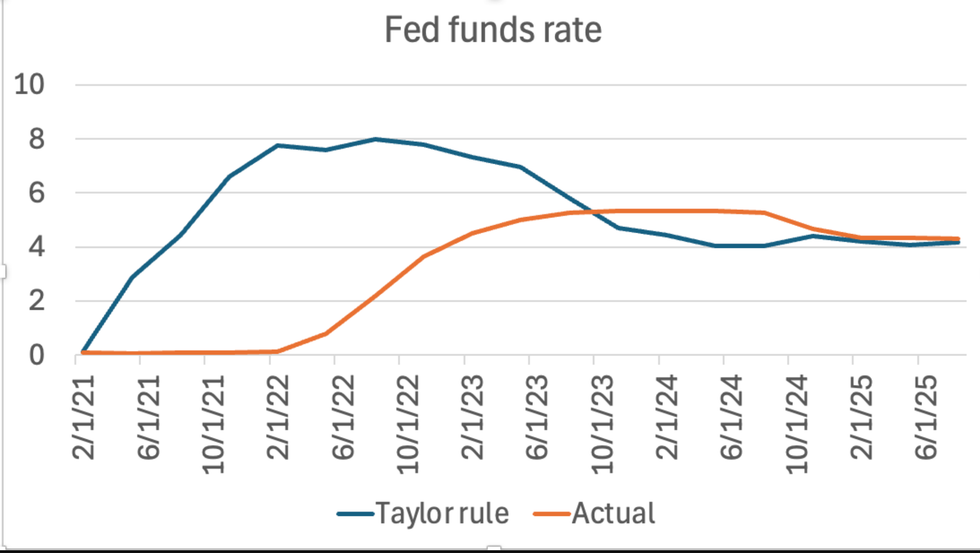

For the wonkishly inclined: We can get more specific about the dual mandate by invoking the Taylor Rule, devised by the economist John Taylor in the 1990s, which offers a formula for setting the fed funds rate based on unemployment and inflation. Or actually I should say Taylor Rules, plural, since there are a number of variants. The Atlanta Fed offers a “Taylor rule utility,” which lets you pick among the variants or roll your own. But most versions say that the current level of rates is more or less right. Here’s what one comparison looks like:

On the other hand, nobody thinks these estimates are precise, and as the Fed statement suggested, there are hints in the data that the labor market is weakening. So a 25 basis point cut is defensible too.

And none of this matters very much. Short-term interest rates, like the fed funds rate, have very little impact on the real economy.

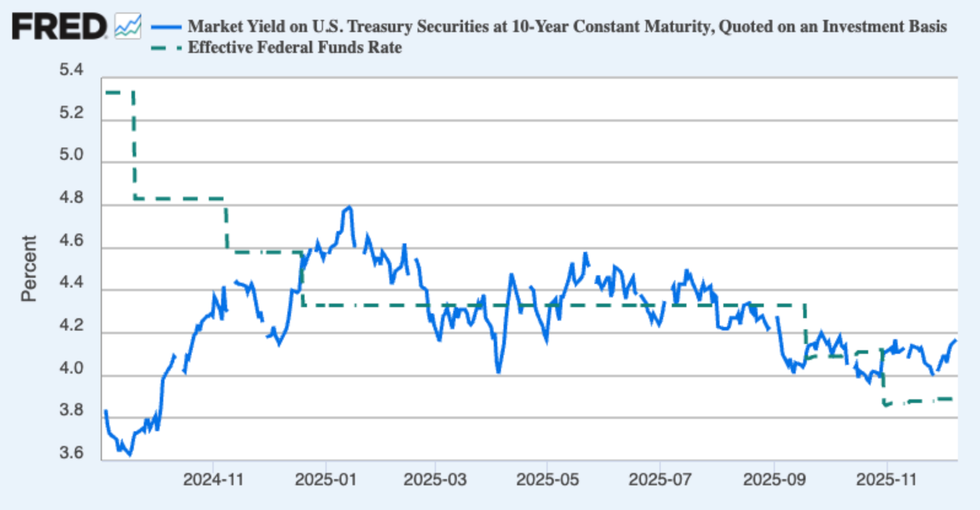

And long-term rates, which matter a lot more than short-term rates, especially for housing, mostly reflect market expectations of Fed policy over the next few years, not the next few months. As a result, long-term rates and short-term rates can diverge. They can even move in opposite directions. The Fed began its current cycle of rate-cutting in September 2024. Since then the fed funds rate has come down significantly but the benchmark 10-year interest rate has gone up from a low of 3.6 percent to the current level of just under 4.2 percent:

What’s that about? Because the Fed tries to fulfil its dual mandate, it normally tries to set interest rates neither too high, which can lead to unnecessary unemployment, nor too low, which can lead to excessive inflation. If you ask me, the Fed should call its target the “Goldilocks rate.” Sadly, however, it’s usually referred to, unpoetically, as r* or r-star.

R-star can’t be observed directly, only estimated. And what has happened since last year is that many estimates of r-star have been marked up, for at least two reasons. First, the tax cuts in the One Big Beautiful Bill will lead to larger budget deficits — no, tariff revenues won’t make up the difference, even if the Supreme Court lets Trump’s clearly illegal tariffs stand. And these deficits will put upward pressure on long-term rates. Second, the AI boom has led to huge spending by tech companies, especially on data centers, which also puts upward pressure on long rates.

So if the Fed continues to operate normally – that is, without political interference -- movements in r-star will be the main driver of future interest rates. In particular, long rates will come down if AI is a bubble and that bubble bursts.

But will the Fed continue to operate normally? Or will monetary policy, like so much else in America these days, end up being ruled by Donald Trump’s whims?

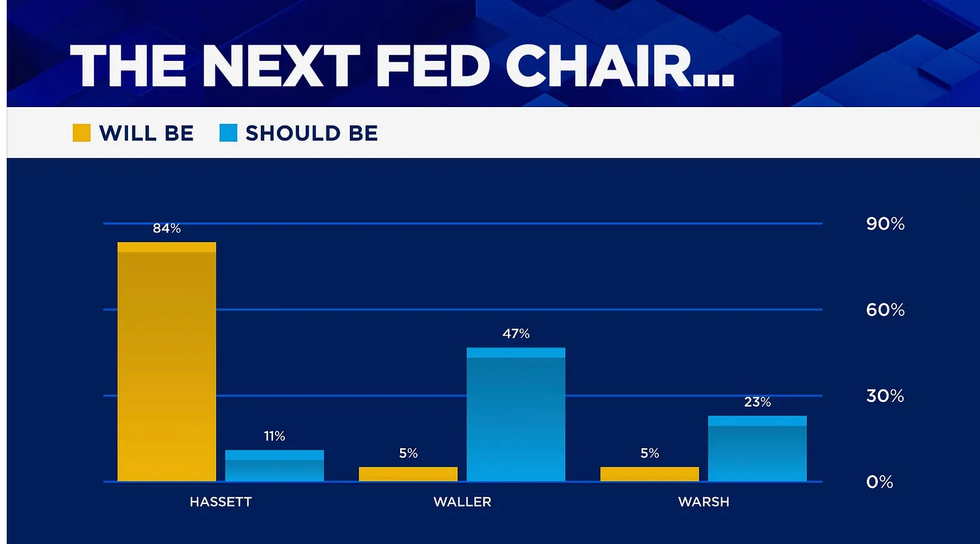

I wrote last week about Kevin Hassett, Trump’s likely pick as the next Federal Reserve chairman, whom I described as an “ideological DEI hire” who is intellectually and morally unqualified for the job. It turns out that I’m not alone in that assessment, although I may be using unusually blunt language. CNBC regularly surveys financial experts for their views on Fed-related matters. According to their latest survey, featured in the chart below, almost all their experts believe that Hassett will get the job, but almost none of them think he should.

And even if Hassett doesn’t get the job, whoever does is almost certain to be totally subservient to Trump. And this will be a negative for the economy. First, if Trump succeeds in controlling monetary policy, he can exact a policy according to his whims, which are both incoherent and dangerous. He is demanding massive interest rate cuts even as he insists that the economy is A+++++ — in which case why does it need these cuts? Nor can we expect him to show proper concern about the inflationary consequences of big rate cuts given that he keeps claiming that overall prices are falling, which is simply false.

And second, even if Trump isn’t able to capture full control over monetary policy through his pick for Fed chair, the effects will still be negative. Because as I pointed out in my critique of Hassett, in times of crisis the Fed chair has to be capable of showing leadership and gravitas, as well as garnering trust. Given that the Fed’s future task has been made especially difficult by Trump’s chaotic policies, higher-than-desired inflation, a weakening job market, very high future deficits, and a falling dollar, installing a Trump sycophant as Fed chair would mean facing any future crisis without any of the reserves of credibility that got us through the global financial crisis in 2008 and the COVID crisis in 2020.

So however this turns out, politics is now what matters for the future of the Fed — not whether we have one or two rate cuts in 2026.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Paul Krugman.

- Who is Kevin Hassett? The rumored Fed pick says inflation is 'way ... ›

- Kevin Hassett, Trump's Likely Pick for Next Fed Chair: What to Know ... ›

- Hassett likely next Fed chair, but most think Trump should nominate ... ›

- Kevin Hassett Wants To Be Fed Chairman. That's What's So ... ›

- Bond investors warned US Treasury over picking Kevin Hassett as ... ›

- 'Scary': Why Kevin Hassett's friends are afraid he'll become Fed chair ›