By Carol M. Ostrom, The Seattle Times

SEATTLE — Since 1996, Dr. Chuck Murry, a University of Washington cardiovascular biology researcher, has been intent on transforming powerful human stem cells into heart-muscle cells that can repair damaged hearts.

Over the years, he and his colleagues have worked through myriad setbacks and complications in studies on mice, rats and guinea pigs, piling up successes as their animal models got larger and physiologically closer to humans.

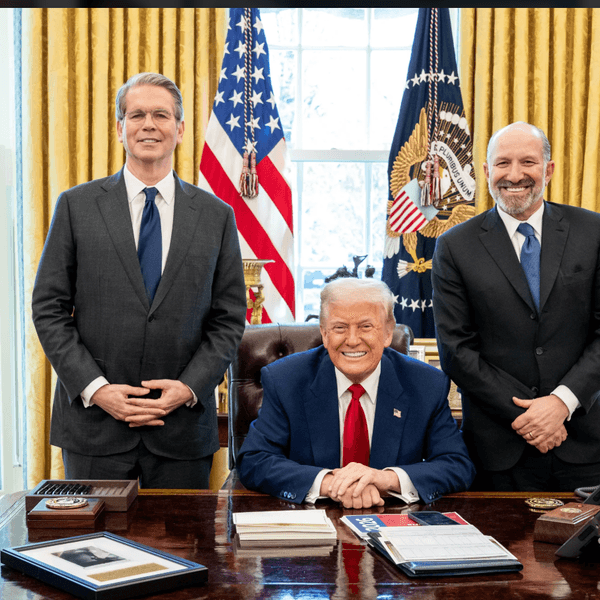

Now, they have successfully regenerated heart muscle in monkeys, Murry and Dr. Michael Laflamme and other colleagues at the UW Institute for Stem Cell & Regenerative Medicine reported in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

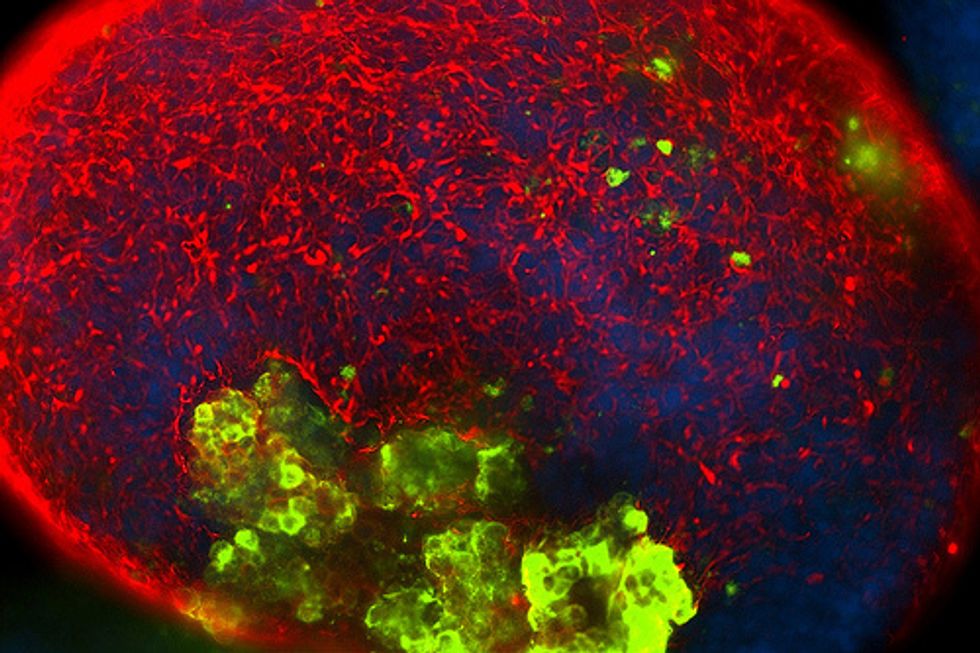

As before, the researchers transformed the human stem cells into heart-muscle cells, this time injecting them into damaged monkey hearts. There, the cells assembled themselves into muscle fibers, began beating in the heart’s rhythm, and ultimately were nurtured by the monkey’s arteries and veins, which grew into the new heart tissue.

“This is 10 times more heart muscle than anybody else in the world has been able to generate,” said Murry, who predicted his lab would be ready for clinical trials in humans within four years.

Dr. Michael Simons, director of the Yale Cardiovascular Research Center, said the research is the first to show that human embryonic stem cells can fully integrate into normal heart tissue. The lab’s impressive “scale up” for production of sufficient newly programmed stem cells for a large-animal heart, which was done by Laflamme’s team, was likely unprecedented, as well.

The Murry team’s latest success, like the others, did not answer every question and had its own complications, but even so, cardiovascular research leaders not connected with the work hailed it as a significant step forward.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Dr. Richard Lee of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It’s very challenging to do such experiments, and being able to show benefit is a “real achievement,” he said.

Murry is “an extraordinarily careful and thoughtful investigator,” Lee added. “When work comes out of his lab it makes us all feel better because we know we can trust it.”

The most serious problem encountered in the research was a period of irregular heartbeats, known as arrhythmias. Although the monkeys’ arrhythmias disappeared after a few weeks, Murry and others said it was concerning.” That’s a very big deal, because that’s what kills,” Simons said. On the other hand, he said, the arrhythmias were not unexpected because of technical issues with larger hearts.

“The question is: How serious are they? How long do they last? Do they go away after several weeks after the tissue matures and the heart matures, or is it a lifelong problem?”

Murry said if his lab hadn’t been monitoring the monkeys 24-7, researchers might have missed the arrhythmias, which didn’t appear to have disturbed the monkeys.

“The monkey is in the cage eating a banana,” Murry said. Meanwhile, “the investigators are freaking out. We’re having the heart attack. But the monkey was OK.”

The six monkeys involved in the study were pigtail macaques, a type commonly used in research.

Heart muscle is inextricably linked to heart failure, which for Murry is Public Enemy No. 1, with worse average survival time than breast cancer, he said.

When a heart attack damages heart muscle, it forms scar tissue rather than growing back. If there is enough damage, the heart may not have enough muscle to pump out blood, leading to heart failure, which Murry calls “a burgeoning public-health problem.”

“It’s really bad now, and it’s going to get worse” as the baby boomer generation ages, he said.

For Murry, his lab’s latest success is bittersweet. His mother, Donna Murry — the inspiration and motivation for his focus on fixing damaged hearts, he said — died last week of multiple infarctions. Heart disease ran in her family, Murry said.” She is the kind of person we would like to have helped,” he said. “My mom would have been so proud.”

UC Irvine via Flickr