Public-Health Officials Go To Court To Stop Man With HIV

By Carol M. Ostrom, The Seattle Times

SEATTLE — In a very unusual step, King County, Wash., public-health officials have gone to court to try to stop a man with HIV who has infected eight partners in the past four years from infecting others.

“We’re not trying to criminalize sexual behavior here,” said Dr. Matthew Golden, director of Public Health-Seattle & King County’s HIV/STD Control Program. “We are trying to protect the public’s health. And we’re trying to make sure that everyone gets the care they need, including the person involved in this.”

The order, issued Sept. 4 by King County Superior Court Judge Julie Spector, requires the man, identified only as “AO,” to follow a “cease-and-desist” order issued in late July by the public-health department requiring him to attend counseling and all treatment appointments made by public-health officials.

If he defies the court order, the judge could order escalating fines or even jail time.

“AO” tested positive at the Public Health STD Clinic at Harborview Medical Center in June 2008, where he was counseled to disclose his status to sex partners and how he should practice safe sex, according to papers filed in the court case.

Since then, despite having received HIV counseling at least five more times, he is believed to have infected eight adult partners from 2010 through this June. Public-health officials said in the court documents that eight people newly diagnosed with HIV had named AO as a partner with whom they’d had unprotected sex.

The officials in July and August served “AO” with “cease-and-desist” orders, the first specifying he attend counseling and the second adding the requirement he seek HIV treatment.

In August, health officials repeatedly made appointments for him to see an HIV medical provider, but the man ignored them. Public-health officials delivered the notice of the last appointment, on Sept. 2, to the house he shares with his mother, who said she would place the notice under her son’s door.

“AO” did not show up for the appointment. The same day, the agency filed for court enforcement of its order, saying his conduct “continues to endanger the public health.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1.1 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and nearly one in six are not aware they are infected.

About 50,000 people in the U.S. become newly infected each year with HIV, which, if untreated, typically progresses to AIDS, which kills more than 15,000 U.S. residents annually.

Golden said it’s not the department’s business to monitor decisions made by two consenting adults — even if it’s risky behavior.

“That is a decision you’re entitled to make in this society,” he said. “Public health doesn’t get involved in that.”

But, he added: “This is not an instance where two knowledgeable consenting adults took a risk.”

By law and inclination, the first option for the department is always “the least coercive,” Golden said. “We have business we need to get done: protect the public’s health. But we are not looking to criminalize people, not looking to routinely put people in jail.”

Only when there is danger to the public health, such as a person with infectious tuberculosis who avoids treatment, do health officials consider the next step.

In the case of someone with HIV, that next step might be more counseling, and eventually, if the problem continues, a cease-and-desist order.

If that is ignored, and the person is “repeatedly coming up as being named as a sex partner for people newly diagnosed with HIV,” Golden said, the public-health agency is empowered under state law, RCW 70.24.024, to seek court enforcement of its orders.

The agency’s cease-desist order requires AO to seek treatment, but does not compel him to comply. As Golden said, “He can go to the doctor and not take the pills.”

By law, the burden of proof in court is on the public-health officer to show why the order is needed, and that the conditions imposed “are no more restrictive than necessary to protect the public health.”

The public-health agency issues such cease-and-desist orders less than once a year, Golden said. It has sought legal enforcement of its orders only once before, in 1993, in the case of a sex worker. That was before effective antiretroviral therapy, Golden said, and the sex worker eventually left the jurisdiction.

Golden said he expects a better outcome this time.

Antiretroviral therapy has improved from a multi-pill, multi-dose-per day schedule to a one-pill, once-a-day dose, he said. Cost shouldn’t be an issue, with a federal grant from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and Medicaid expansion, he said.

Golden, an HIV doctor for 20 years, has met “AO.”

“I think the patient is going to take his meds,” he said. “The goal here is not to send the patient to prison; the goal is to get him to adhere to the health order. I am very optimistic that we are going to make progress here.”

“We are trying to protect the public’s health. And we’re trying to make sure that everyone gets the care they need, including the person involved in this.”We are trying to protect the public’s health. And we’re trying to make sure that everyone gets the care they need, including the person involved in this.”

Dr. Matthew GoldenHIV/STD programStatement from Public HealthPublic Health – Seattle & King County’s primary goal is to ensure that all HIV-infected persons, including the person for whom we recently sought enforcement of a health order, know their HIV status and receive the medical care they need. HIV treatment helps protect both the health of infected persons and the health of the community as a whole. All of our work related to the case in question has been designed to ensure that an HIV infected person receives needed medical care and adopts behaviors that protect both him and his sex partners.

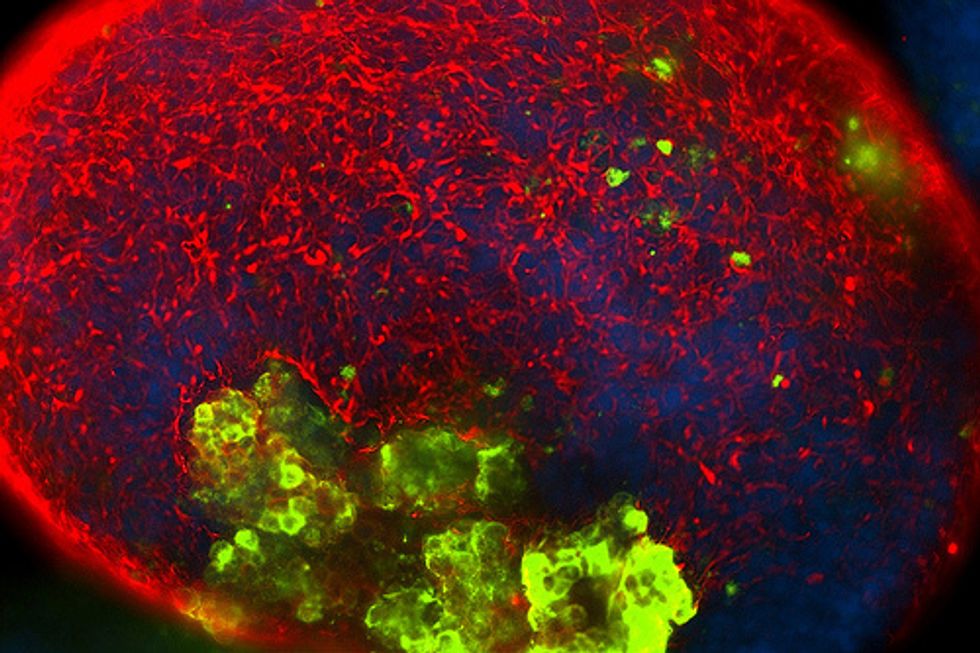

Photo: Daniel Schwen via Wikimedia Commons