WASHINGTON — Deals involving limits on weapons, nukes, or otherwise, are intricate and technical. Only a limited number of people among arms-control connoisseurs fully grasp the meaning of every detail.

Yet in a democracy, these matters are and should be the subject of debate. Those engaged in the argument sometimes pretend to more knowledge than they have, tossing out a raft of numbers — readily available courtesy of your favorite newspaper — on centrifuges, enrichment, and the like. Others are somewhat more candid in acknowledging that their view is shaped by what they thought before a single fact was published, though they, too, will rattle off a few data points just to enhance their credibility.

And so it was with the framework of the agreement announced on Thursday designed to keep Iran from developing nuclear weapons, or, at the least, kicking the prospect of a nuclear Iran down the road a decade or so. The fact that it’s a “framework” and that the final deal won’t be reached for a few months creates wiggle room for everyone. And the United States has been far more forthcoming than Iran in disclosing details, suggesting there are still fuzzy parts.

Just to be clear, I am not immune from my own critique. I welcome this deal, or pre-deal, because going in, I supported the idea of trying to get Iran to postpone getting a weapon. This is better than the alternatives, including war or an effort to keep sanctions going with allies who are not likely to support them, especially if the United States scuttles the talks.

I also see the possibility — not a probability, but a chance — that an agreement could open Iran up and strengthen those inside pushing for more freedom. Lest you think this is foolish, consider that both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher thought that betting on Mikhail Gorbachev could lead to change in the Soviet Union. (“I like Mr. Gorbachev,” Thatcher said. “We can do business together.”) Many of their traditional supporters thought they were dangerously wrong, possibly naive. But they were right.

Moreover, I don’t think that we should give Saudi Arabia or other Sunni states a veto over our foreign policy, and I do think that in the long run, Israel will be safer, not in greater danger, if we can contain Iran in this way. Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu emphatically disagrees, but I suspect that if the U.S. gets the deal it wants, many American supporters of Israel will take issue with him.

But there is something else reassuring about this first round: The outline is tougher and more specific than many skeptics thought it would be. Yes, Secretary of State John Kerry and the Obama administration managed expectations well. But among open-minded skeptics, the tilt was toward pleasant surprise.

It’s true that the facts as we know them are being read differently, depending on the orientation of the reader. President Obama says the inspections envisioned will be “robust and intrusive.” His critics say they aren’t nearly intrusive enough. Supporters of the deal note that the number of centrifuges Iran will be operating to enrich uranium is being cut from 19,000 to 5,000. Critics say Iran will still be running 5,000 centrifuges and is not being asked to destroy the rest. And they worry that the sanctions on Iran will be removed too quickly and not in stages.

Nonetheless, even some who are far from sold on the framework acknowledge it contains some useful measures: limits on the enrichment of uranium, the conversion of the underground nuclear facility at Fordow into a “research center,” and keeping a reactor in Arak from being able to produce weapons grade plutonium. I offer this paragraph not to pretend to any expertise on these matters, but to suggest the utility of a kind of intellectual triangulation: If even those inclined to be skeptical of a deal think these are positive elements, they are almost certainly steps forward.

You’d like to think that on a matter this important, those involved in the debate would acknowledge ambiguities and uncertainties and that each side would admit it’s placing a bet — on hope or skepticism. I’m not holding my breath. Sen. Mark Kirk (R-IL) is normally a sensible sort. But referring to the State Department’s top negotiator, he told a radio interviewer that “Neville Chamberlain got a lot more out of Hitler than Wendy Sherman got out of Iran.” It’s not a promising way to start.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com. Twitter: @EJDionne.

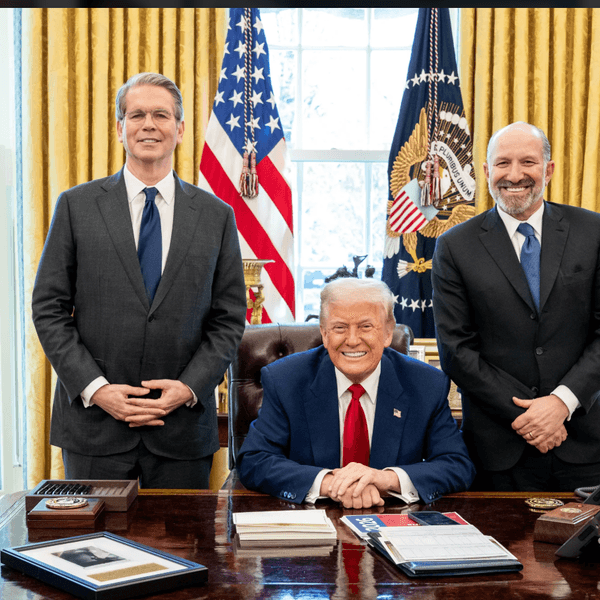

Photo: U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry with Foreign Minister Javad Zarif of Iran in Vienna, Austria, on November 23, 2014, before the two begin a one-on-one meeting amid broader negotiations about the future of Iran’s nuclear program. (U.S. State Department photo/ Public Domain)