Why Hasn't The Tea Party Returned To Protest Biden's Big Spending?

Writing for the HuffPost,, reporter Igor Bobic published a fascinating piece finding that Republicans are optimistic that President Joe Biden's generous spending policies will trigger a second wave of the Tea Party that erupted under President Barack Obama. But as of yet, no such movement has emerged, despite the strong parallels between Biden and Obama's first days in office.

So what explains the difference? Bobic picks up on several plausible reasons, but I think he leaves some out.

For many, the most plausible explanation is the fact that Obama's race inspired a bigoted backlash that Biden has avoided:

Another reason why Biden may not face as much resistance as Obama did is the fact that he's a white man in his 70s who has been in the public spotlight for decades. The Tea Party movement was fueled by race as much as economics ― a trend that continued into the Trump years. The election of a Black president for the first time in U.S. history galvanized a segment of the Republican Party, leading to the racist "birther" conspiracy theory that Obama wasn't born in the U.S., a false notion that eventually put Trump, a top birther, into the Oval Office.

This is undoubtedly a big part of the explanation, but it's not the complete story. After all, many argued persuasively that racism was a big factor in Donald Trump's 2020 win, and that happened against Hillary Clinton, a white opponent. So even if we believe racism was the primary motivation behind the Tea Party, that doesn't rule out that such a movement could arise in opposition to a white president.

Obama and Biden differed in many ways apart from race (though it may be a factor in explaining some of the other differences.) Obama's 2008 candidacy was sold and recognized as a major turning point in American politics. He promised "change" and argued for upending the Washington order. That was a welcome message to many in the country, winning him the presidency and broad popularity early on, but it made many of his detractors uncomfortable and wary, perhaps especially those who were already prejudiced toward him because of his race.

Biden, on the other hand, ran as a return to normalcy. And not only was that his message, but the media, much of the country, and even his critics seemed to believe that's what he was offering. The central narrative of the 2020 Democratic primaries was that Biden was the most moderate (and perhaps electable) of all the candidates, and that image stayed with him even as he surprisingly tacked left on policy during the general election campaign. It's true that being a white old man helped Biden sell the idea that he represents a return to the status quo, but that's the message he was intentionally offering to the public, in stark contrast to Obama.

The circumstances of the crises that Biden and Obama faced are also vital to understand. Like Obama, Biden took over the presidency in the midst of a deep economic crisis and pushed through a largely partisan spending package to help the country recover. But while Republicans were able to mock and demonize the 2009 stimulus package, their opposition to Biden's 2021 American Rescue Plan has been negligible. Perhaps as a result, it's highly popular — as are Biden's other taxing and spending plans.

Bobic pointed out one key factor to explain why the American Rescue Plan is more of a political success than the Obama stimulus — it helped the vast majority of Americans directly by sending them checks or direct deposits:

Turns out, people are less displeased with spending when it puts dollars in their pockets, as Republican Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.) acknowledged to HuffPost this week.

"Even my counties back in Indiana are happy, which is a very conservative area," said Braun, a deficit hawk. "They're asking, 'How can I spend $15 million in a rural county?' I think the spending part of it was smart politically because they put a sugar high out there and put a smoke screen to how radical some of the legislation may end up being."

(Biden's ARP is also bigger and better attuned to the crisis at hand than the Obama stimulus was in 2009, which makes it more likely that the economy will recover better this time around and reduce the risk of backlash going forward.)

Another important factor, though, is that big spending in the face of the coronavirus pandemic was already a bipartisan success story. Democrats and Republicans jointly passed a series of bills at the start of the pandemic, pumping trillions of dollars into the economy, and then they passed another nearly trillion-dollar package at the end of December 2020. While Republicans opposed ARP under Biden, it was hard for them to make a principled stand against it, because they had largely supported previous bills that looked quite similar. They could say the new bill was excessive, but they couldn't argue it represented the road to tyranny.

Meanwhile, Trump himself had objected to the fact that the direct payments in the December package had only been $600 per person — he wanted them to be $2,000. Congressional Republicans largely opposed this change, but it ended up in Biden's plan — forcing any Republicans who would strongly oppose the provision to stand in opposition to Trump, still the de facto leader of their party. And when he was president, Republicans didn't shy away from deficit spending — most notably with $2 trillion in tax cuts — even when the economy was doing well.

Bobic noted that Trump's positioning with the GOP generally makes it hard for Republican officials or the party base to take a stand against Biden's spending agenda:

The biggest obstacle to the rise of another conservative political movement may be Trump, who as president repeatedly prodded his party to embrace higher government spending. The former president continues to suck up oxygen among the right, dangling endorsements to 2022 candidates and issuing threats to campaign against Republicans who crossed him in the past.

Few Republicans want to lead an opposition movement to Biden that ends up putting them crosswise with Trump, who is more important to many party members than any particular policy position.

Obama's predecessor, President George W. Bush, had been a profligate spender too, of course. But this didn't bother the conservative activists in 2009 claiming they were opposed to Obama's spending. As mentioned, much of the Tea Party was a thin cover for racism. But to the extent they felt obliged to criticize government deficit spending on principle, they weren't constrained by a need to hold the Bush party line. His popularity was in the gutter, his legacy was in tatters, and his political career was over.

And one policy from the Bush years likely plagued Obama in a way that has no parallel for Biden: The Troubled Asset Relief Program, a.k.a. TARP, a.k.a. the bank bailout. The bailout of financial institutions that had heavily invested in subprime mortgages was deeply unpopular and seen as a corrupt giveaway to the very people who caused the 2008 financial crisis. And though it was passed with bipartisan votes through Congress and signed by a Republican president, it hung over much of Obama's response to the crisis, likely dragging down support for other actions he took that might otherwise have been more popular. There was a widespread sense, not unfounded, that the bankers had been saved while ordinary Americans were left out in the cold. Obama declined or was unable to take steps that would have directly helped families in more tangible, concrete ways, and the economy took longer to recover as a result.

Biden benefitted from having nothing like TARP to cope with, and as explained, the direct spending provisions of ARP ensured that the American people were personally benefiting from the federal government's actions. That makes it harder to gin up opposition than if people believe others are unfairly benefiting from the government's largesse.

And despite the rampant failures of the previous administration and Trump personally to respond appropriately to the coronavirus pandemic, most people actually seem prone to view the crisis as no one's fault in particular. This is a major difference with the 2008 crisis, which was seen by many as the fault of the big banks, the financial industry, and government regulators. Elements of this populist and even leftist anger made their way into the Tea Party rhetoric, even if they served the larger purpose of a right-wing movement. There have been some leftist and populist critiques of the U.S. economic response to the coronavirus crisis, but they haven't gained nearly as much traction.

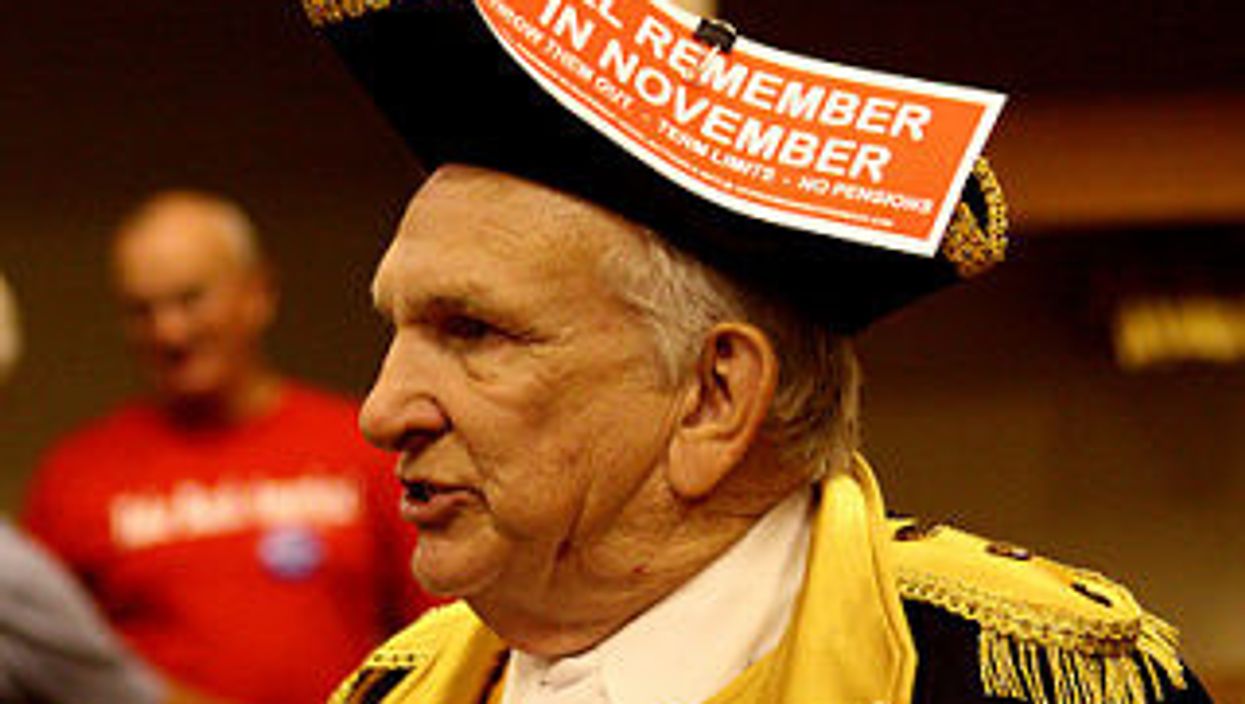

There is a signficant caveat to this whole argument, because in one way Biden is facing his own version of the Tea Party. But this time, it doesn't come in protesters wearing funny hats, but the large group of people, primarily on the right, who are opposed to getting the coronavirus vaccine. It's not clear yet how large and formidable this segment of the population is, and how much it will impact the road to life beyond the pandemic, but it does seem to descend from many of the same strains of anti-government sentiment that came out of the 2009 Tea Party.

But the anti-vaccine movement isn't as welcome to the Republican Party as the Tea Party was, and it isn't likely to have as much staying power — assuming the pandemic recedes and becomes a less significant political issue. It's hard to see how one could build a governing agenda around anti-vax ideology, especially if the coronavirus fades.

None of this means, however, that Biden is in the clear. He may avoid a Tea Party-style backlash, but political perils abound. Republicans may well find issues of Biden's own making, or unforeseen events, that they can successfully weaponize against him and quash his political ambitions. It's possible the economy could recover and the public will turn against Biden's spending, though this largely seems like right-wing wishful thinking. At this point, following the GOP's Obama-era playbook doesn't show much hope of success.