Alabama Firm Took PPP Loan, Then Moved Plant To Mexico

Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

Late last summer, after churning along through the pandemic with only a two-week pause, managers at FreightCar Americacalled hundreds of workers into the break area at the company's factory near Muscle Shoals, Alabama, to tell them that the plant was closing for good.

For some employees, the news wasn't a shock: They'd been hearing rumors that management would move the work elsewhere for years. The timing, however, seemed odd. Only a few months earlier, the publicly traded company had received a $10 million Paycheck Protection Program Loan — the maximum amount available under a pandemic relief program designed to keep workers employed. Some had believed the funds would keep the doors open for a little while longer.

Nevertheless, the plant's managers announced that all production would move to FreightCar's new facility in Mexico, which meant most of the assembled workers would lose their jobs.

Jim Meyer, FreightCar America's CEO, told ProPublica in an email that he had not intended to shutter the plant when he received the PPP money, and that it had allowed the company to keep workers on the job through most of 2020 despite a sharp dropoff in new orders.

Robert Bulman, however, thinks the $10 million just helped FreightCar's Shoals plant keep producing while company officials got ready to shut it down.

"When the Mexican plant opened, we were told at the beginning they would just be helping Shoals and making parts for the trains," said Bulman, who worked at the Alabama plant for seven years before getting laid off last year. "But the whole time, it was a setup, we were gone."

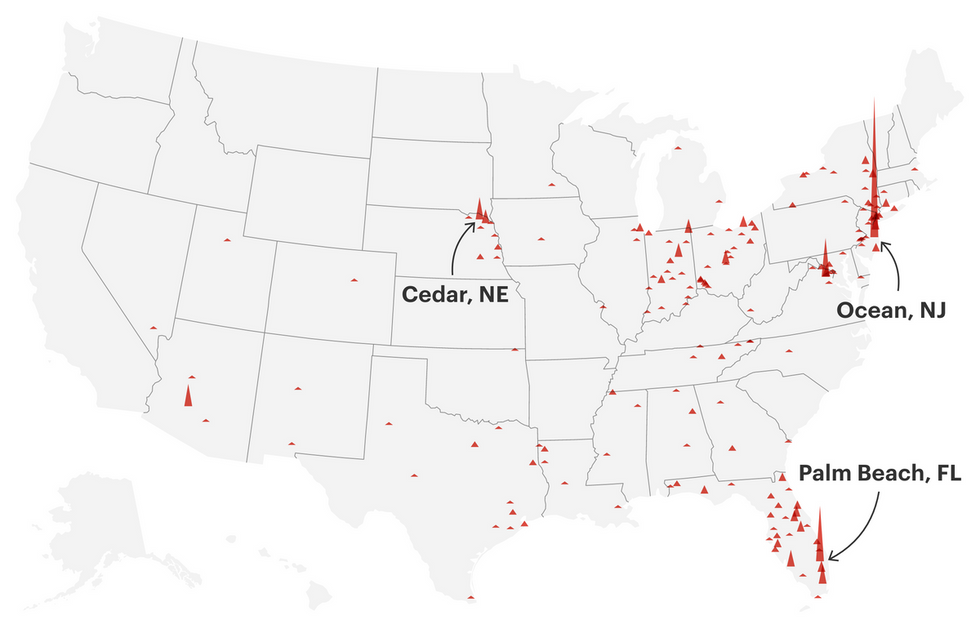

FreightCar America isn't the only large company to have taken out a multimillion-dollar Paycheck Protection Program loan and then laid off a substantial chunk of its workforce. An analysis of applications for trade adjustment assistance, which the federal government provides to workers whose jobs have disappeared due to imports, shows that at least half a dozen companies that applied for more than a million dollars apiece in PPP loans terminated more than 50 workers in 2020 after their aid was approved.

To be clear, the companies may have complied with program rules, which put a premium on getting money out fast. The regulations changed frequently in the months after the Congress established the PPP as part of the CARES Act in March 2020, and the law was later amended to allow more of the money to be used for non-payroll expenses. The law also contained many exemptions that stretched the definition of what qualifies as a small business.

A paper mill in northeast Washington state called Ponderay Newsprint, for example, went bankrupt and laid off 150 workers, two months after being approved for a $3.46 million loan. Its bankruptcy trustee John Munding said the money was used to pay workers and the government forgave the loan, while the company's assets were acquired by a private equity firm.

A Nebraska aircraft parts manufacturer called Royal Engineered Composites was approved for $2.74 million in April 2020 in order to support 250 jobs, but laid off 99 workers by mid-May. The company declined to comment.

Canadian-owned Supreme Steel took $1.69 million in May 2020 for its plant in Portland, Oregon, which it closed five months later, terminating 112 employees. Spokesperson Rhandi Berndt said that "the closure was the result of market forces" and declined to answer further questions.

In order for PPP loans to be forgiven, the federal Small Business Administration initially required borrowers to spend 75% of the funds on payroll over eight weeks. Since the maximum PPP loan amount was for 2.5 times companies' average monthly payroll in 2019, that should have guaranteed that wages and hours could be maintained, as required by the CARES Act.

In the case of FreightCar and some other borrowers, the original eight-week "covered period" of the PPP loan passed before layoffs occurred, allowing the companies to have their loans fully forgiven. But the other cases may have easily qualified as well, because Congress changed the rules.

Last June, after businesses protested that they couldn't spend their PPP money fast enough in a stalled economy, the legislation was amended to require only that 60% of a loan go toward workers' pay, and the covered period was extended to 24 weeks. Since borrowers had to spend less of the loan on payroll over a longer period to keep the money, they had wide leeway to let people go as they saw fit.

"It wouldn't be difficult to lay off 50% of your workforce and still get full forgiveness," said Eric Kodesch, an attorney at Lane Powell who has helped many clients with their PPP applications.

The SBA has not publicly released data on forgiveness of specific loans, but aggregate statistics show that so far, out of all applications processed, more than 99% of the total dollar value has been forgiven. The SBA declined to comment on individual borrowers or identify loans that have been forgiven.

There's another reason why a casual reader of the CARES Act might think companies would not qualify for PPP money: Many are actually very large businesses.

In general, the CARES Act set an upper size limit of 500 employees. With a few exceptions, the law required SBA to count all "affiliate" companies toward that total. That would include companies owned by private equity firms as well as subsidiaries contained within holding companies. It exempted hotels, restaurants and franchises, but no other industries. (That's why Shake Shack and Ruth's Chris Steak House qualified for loans, though each returned the money after a barrage of negative press coverage.)

However, a number of program nuances allowed large companies to obtain PPP loans.

FreightCar laid off 550 people with the Shoals plant shutdown, according to a notice filed with the state of Alabama. Along with its headquarters employees, that alone would exceed the PPP's ostensible 500-employee cap. But FreightCar availed itself of a loophole baked into the PPP. The SBA's alternative size standards, a complex set of industry-by-industry thresholds that have been debated for decades, allowed it to qualify with up to 1,500 workers.

Originally, the SBA allowed foreign-owned applicants to count only their U.S.-based employees under the 500-person cap. That guidance changed last May, requiring foreign-owned applicants to count their entire global workforce. But plenty of companies had already gotten PPP loans, and were allowed to keep them.

For example, Ledvance LLC, a Chinese-owned global lightbulb manufacturer operating in the U.S. under the brand name Sylvania, was approved for a $9.36 million PPP loan in April 2020. Then, between May and July, it laid off 50 people while closing down a distribution center near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Ledvance spokesperson Glen Gracia said in an email that the layoffs were "unrelated to the pandemic and in full compliance with LEDVANCE's participation in the Paycheck Protection Program."

Then there's Chick Master Incubator Company, which took $1.34 million in April 2020. In June, its corporate parent — a Zurich-based private office that invests the fortune of a long-established industrialist family — announced it would combine Chick Master with its other hatchery holdings and close the plant, laying off 68 people in Medina, Ohio, by year's end. Chick Master didn't reply to a request for comment.

One type of applicant, however, still likely should not have qualified: companies controlled by private equity firms whose total holdings exceed the SBA's size standard for the borrowers' specific industries. Cadence Aerospace, a supplier of aerospace and defense parts that itself has bought three companies in the last three years, is majority-owned by Arlington Capital, a private equity firm managing billions of dollars. Cadence was approved for a $10 million PPP loan in April 2020, and later that month laid off 72 people at its Giddens Industries subsidiary in Washington state, according to a notice filed with the state. Arlington Capital did not respond to a request for comment.

The Shoals plant was the last remaining U.S. manufacturing facility for FreightCar, a 120-year-old company headquartered in Chicago that had been shrinking its U.S. footprint for years. In 2008, it shuttered its plant in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. In 2017, it shut down its factory in Danville, Illinois. In 2019, it closed its plant in Roanoke, Virginia and announced it would open a new facility under a joint venture in Castaños, Mexico. When executives informed investors in September that the Shoals facility would also close and manufacturing would shift to Mexico, they projected $25 million in overall savings, including a 60% reduction in labor costs.

"Our manufacturing transformation is now largely complete, and we have taken control of our own destiny," Meyer said on an earnings call in March. "We have dramatically repositioned our competitive profile and in so doing created a new company, one that is able to win."

In 2013, the future looked different. When the Shoals plant opened, it offered about $12 an hour to start and a chance at advancement. One worker, who asked not to be named in order to protect her future employment prospects, left a tile-making job to become a welder, constructing a variety of rail cars, from hoppers to gondolas. Soon, she moved up to air brake tester, sliding underneath the massive steel vehicles to fix pipes.

"I went to FreightCar to retire," said the worker. "I wasn't planning on leaving when I got there."

In the following years, safety, pay and management concerns led to a union drive. During the campaign, anti-union employees circulated flyers warning that the plant would shut down if workers voted to organize, and in 2018 they voted decisively against it.

As it turned out, the Shoals facility wouldn't last long anyway.

Leading up to 2020, FreightCar touted the Shoals plant's competitiveness. A marketing video showed production lines run by industrial robots and skilled workers. "This is the largest, newest, most purpose-built factory in North America," boasted Meyer. "A modern, state-of-the-art factory in every sense of the word."

But the company was still losing money, to the tune of $75.2 million in 2019. When the pandemic further slowed down orders, executives started talking up the new facility in Mexico instead.

"The Mexico labor rate is approximately 20% of that in the U.S.," Meyer said on an earnings call in August 2020. "And the new plant provides other sources of savings beyond just labor."

Also on the August earnings call, executives explained that loan proceeds had made up for some of the cost of the company's move to Mexico. Chris Eppel, then the company's chief financial officer, said that the money also "partially offset" operating losses and inventory purchases. Meyer still got his $500,000 base salary in 2020, plus stock options worth nearly that and a $1 million bonus for securing a $40 million loan from a private investment company.

FreightCar did not take out a second-draw PPP loan; updated rules excluded publicly traded companies.

After the plant closure announcement, the air brake tester found a job making dashboards and bumpers for Toyota. It takes three times as long for her to get to her new job as the 20-minute drive she had to FreightCar, and she's paid six dollars less per hour. Although FreightCar gave employees a few thousand dollars in severance payments, she said all of hers went towards bills.

"It's like starting all over again," she said. "If they did right by us like they did their supervisors, maybe we'd be in more decent shape than what we're in now."