Reposted with permission from Alternet.

Not to put too fine of a point on it, but Ken Starr is accused of ignoring sexual violence at Baylor University mostly because doing something about it would have jeopardized a cash cow. In his near six years as president of the school, Starr led an administration that law firm Pepper Hamilton concluded“as a whole failed” on every front to adequately address or attempt to investigate sexual assaults carried out by student athletes. Last week, the school’s Board of Regents issued a statement that it was “shocked and outraged” by the gross “mishandling of [sexual abuse] reports,” and announced it was firing head football coach Art Briles, sanctioning and placing on probation athletic director Ian McCaw and demoting Starr from president to chancellor. Days later, Starr announced he was stepping down from that role, but would continue to teach law at the institution.

Starr, who was once the special prosecutor behind the investigation that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, now has a place in the pantheon of finger-wagging moralists turned scandalized figures. The man who let slip—or rather, leak—into the public record every titillating detail of Clinton’s sexual indiscretions has, as Baylor president, been decidedly less transparent abount grave and disturbing instances of sexual misconduct on his own campus. The contrast between the Starr of nearly two decades ago and today seems a complete inversion. It seems worth it to question why.

In the meantime, let’s review some of what we now know about what happened during Starr’s Baylor tenure, a period during which the school football team’s meteoric rise seems to have come at the cost of its female students’ well-being. Here are 12 things you should know about the rape scandals at Baylor.

1. Baylor ignored new federal mandates regarding sexual assault investigations.

In April 2011, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights sent every college and university that receives federal funding (essentially all but a scant few schools nationwide) a letter reasserting and clarifying the legal requirements according to Title IX. Popularly referred to as the “Dear Colleague”letter, among numerous other responsibilities the 19-page document placed particular emphasis on the need for institutions to hire a dedicated Title IX coordinator. For three years, until November 2014, Baylor failed to comply with that regulation, instead allowing sexual assault investigations to be handled by untrained and underprepared senior school officials, including football staff.

2. Baylor makes huge money off sports, and profits allegedly drove decision making.

Baylor athletics raked in $106.1 million in revenue during the 2014-2015 school year, according to CBS Sports, which based its estimate on figures reported to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Education.

3. Football culture ruled at Baylor.

The chapel of football worship at Baylor sits in the school’s McLane Stadium, which it spent $266 million to open in 2014. The arena’s 45,000-plus seats are regularly filled with sold-out crowds, a testament to the immense popularity of the team in its Waco, Texas, hometown. ESPN notes that Starr was often seen rooting for the school’s various sports teams from the stands, and “was popular among students for his participation in the ‘Baylor Line,’ a school tradition in which freshman students wear yellow shirts and rush the field before home football games.” Joe Nocera at the New York Times writes that Baylor spokesperson Lori Fogelman’s voicemail message ends, “Sic ‘em Bears!”

4. A former advisory board member says the school was well aware of its athletes’ rape issues.

Earlier this year, ESPN’s Outside the Lines spoke with Michele Davis, who until 2014 served on a Baylor advisory board that examined how sexual assaults were handled with community stakeholders. She told the outlet that Baylor’s advisory board was concerned enough about sexual assaults by athletes that it “recommended that someone from the athletic department join the board.” That still is yet to happen.

Davis is also the “sexual assault nurse examiner for McLennan County,” a role that often entails being the first person to speak with sexual abuse survivors who arrive at area hospitals following their assaults. She says the university’s rape problem is outsized.

“Baylor has more sexual assault cases—that we do exams on—compared to the other schools with the same approximate population,” Davis told ESPN, referring to the two other Waco-based colleges.

She reports that she engages with approximately eight Baylor students annually. Davis also estimates that Baylor athletes, just 4 percent of the male undergraduates at the school, comprise somewhere between 25 and 50 percent of alleged sexual assault perpetrators.

5. Six women reported being sexually assaulted by a single football player, but their reports were ignored.

ESPN’s investigation found that six different women, speaking with police, implicated Baylor linebacker Tevin Elliott in sexual assaults that took place between October 2009 and May 2012. Baylor administration officials would not disclose to the outlet when the school became aware of the alleged assaults, but ESPN was told internal records indicate the university had knowledge of a separate 2011 “misdemeanor, sexually related assault citation” against Elliott made by student at an area community college. (Elliott, who was sentenced to 20 years in jail in 2014, told ESPN writer Paula Lavigne the charge never came up with any of his coaches.) The first time media became aware of any of the allegations facing Elliott was when he was arrested. Previously, football coach Art Briles had publicly stated that Elliott was suspended indefinitely for an unspecified “violation of team policy.”

6. A sexual assault victim was told by an administration official to “hope for the best.”

One of the women allegedly assaulted by Elliott told ESPN that she and her mother were directed by Baylor officials to meet with Bethany McCraw, the school’s chief judicial officer. That’s when they learned of Elliott’s five other alleged victims—news which left them justifiably confused by the school’s lack of action.

“I’m like, oh my gosh, six?” the woman, who ESPN calls “Kim,” told the publication. “We essentially asked, ‘Well, why are there six?’ and, ‘Well, does the football team know about this? Does Art Briles know about this?’ And [McCraw] said, ‘Yes, they know about it, but it turns into a he said-she said, so there’s got to be, actually a court decision in order to act on it in any sort of way.'”

But as ESPN notes, that isn’t true. Title IX explicitly states that a criminal investigation does not absolve the school of its responsibility to conduct its own inquiry. The student contends that when she requested a restraining order, McCraw informed her the best the school could do was write Elliott a letter telling him to keep his distance. “[A]nd then you kind of hope for the best,” the official allegedly stated.

7. Baylor officials allegedly pushed one survivor and her mother to get over it and stop pestering them.

Jasmin Hernandez, who says she was raped by Tevin Elliott in 2012, filed a Title IX lawsuit against Baylor in March. In court documents, she alleges a pattern of clear and utter disregard by administration officials in the days and weeks following the alleged attack. After reporting the crime to Waco police, Hernandez called her mother, who flew to campus the next day. One of her first actions was to contact Baylor Counseling Center, both to make them aware of the rape and to request followup counseling services, which are mandated by Title IX. The suit states that she was first told the center was “too busy” to see her daughter. She then reached out to the psychology department at Baylor’s Student Health Center in search of services, but was told “all counseling sessions were full.”

Days later, she telephoned Baylor’s Academic Services Department and was informed that “if a plane falls on your daughter, there’s nothing we can do to help you.” She called Briles’ office and was told by a secretary that the “office had heard of the allegations and were looking into it.” Hernandez’s father also placed calls to the office several times, but never received a response.

8. When the school did investigate, it allegedly did an incredibly poor job.

In 2013, Baylor football player Sam Ukwuachu was accused of rape by a soccer player at the university. In response, the school initiated a Title IX investigation so poorly handled a judge later refused to allow Ukwuachu’s lawyers to refer to it during his 2015 trial. According to Texas Monthly, the school’s examination of the case “involved interviewing just Ukwuachu, his accuser, and one friend of each, and…the school never saw the rape kit collected by the sexual assault nurse examiner.”

The school also reviewed results of “a polygraph test Ukwuachu had independently commissioned,” which are almost never admissible in court. The school cleared Ukwuachu in the matter and pursued no disciplinary action against the player.

9. Baylor made a concerted effort to keep various accusations against players quiet.

In May 2013, Ukwuachu transferred to Baylor from Boise State, where he had been removed from the football team for violent behavior toward a woman. According to Texas Monthly, in a press interview that year, Ukwuachu alluded to the fact that Baylor’s coaches weren’t in the dark about what had gotten him kicked off the team; he stated they “knew everything and were really supportive.” (Baylor coach Art Briles has said he was unaware of the conditions precipitating Ukwuachu’s removal, while Boise coach Chris Petersen has refutedthat claim.) Baylor attempted to secure a waiver so Ukwuachu could play football without having to wait out the one year required of athletes who transfer. Per Texas Monthly, “Boise State informed the school that they would not be providing a letter of support.”

Ukwuachu then had to sit out a second season after he was indicted on rape charges in June 2014, a fact that remained unknown to the press, because Briles obliquely cited “some issues” for keeping the player on the sidelines. Just weeks before the start of Ukwuachu’s 2015 rape trial, Baylor Bears defensive coordinator Phil Bennett told attendees of a luncheon that the defensive end would finally be playing in the coming season.

Ukwuachu was sentenced to six months in county jail and 10 years probation in August 2015.

10. There are more recent cases of sexual assault involving a football player and frat member.

Jacob Anderson, president of Baylor’s Phi Delta Theta chapter, was arrested in March for charges related to the alleged drugging and rape of a woman following a fraternity party. Shawn Oakman, a former defensive lineman for the Baylor Bears who had been regarded as a likely NFL pick, was arrested in April for sexual assault.

11. Starr has continued to hold up Art Briles as a model for players, even in recent days.

Despite law firm Pepper Hamilton’s findings that suggest Briles, as well as numerous other football staffers and top administrators, elevated football above student safety and pretty much all else, Starr continues to sing his praises. In anESPN interview Wednesday that NBC Sports called a “a PR disaster for Baylor,” Starr called Briles “a person of genuine character” as well as “an iconic father figure who is a genius.”

“Coach Briles is a player’s coach,” Starr said, “but he was also a very powerful father figure.”

12. Starr’s recent comments show he hasn’t learned anything from this controversy.

“We’re an alcohol-free campus,” Starr said in that same interview. “It’s not happening on campus, to the best of my knowledge. They are off-campus parties. Those are venues where those bad things have happened.”

NBC Sports responded with a drubbing so well done it deserves to be cited here:

But those bad things happened involving representatives ofyour university and football program, andyour coaches reportedly interfered with the investigation process, thus protecting them from more extreme punishment and failing to give your victims, who are students at your university, a fair chance at justice in any form possible. Just because an incident happens off your campus, does not mean you are excused from failing to uphold the investigation process and response accordingly. Your students may not live on your campus, but they are a part of your community and it is your job as a university to assure all students they can feel safe and secure while attendingyour university.

Kali Holloway is a senior writer and the associate editor of media and culture at AlterNet.

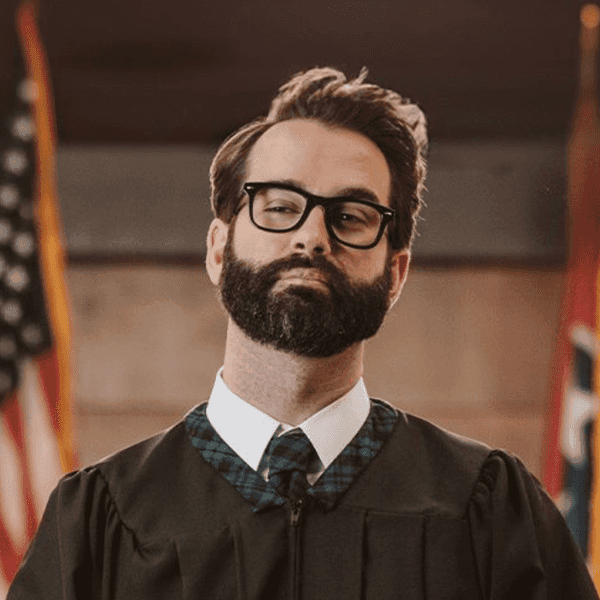

Photo: Attorney Kenneth Starr speaks during arguments before the California Supreme Court to overturn California’s Proposition 8 in San Francisco, California March 5, 2009. REUTERS/Paul Sakuma