Why Ezra Klein Needs To Look More Closely At His Own Housing Chart

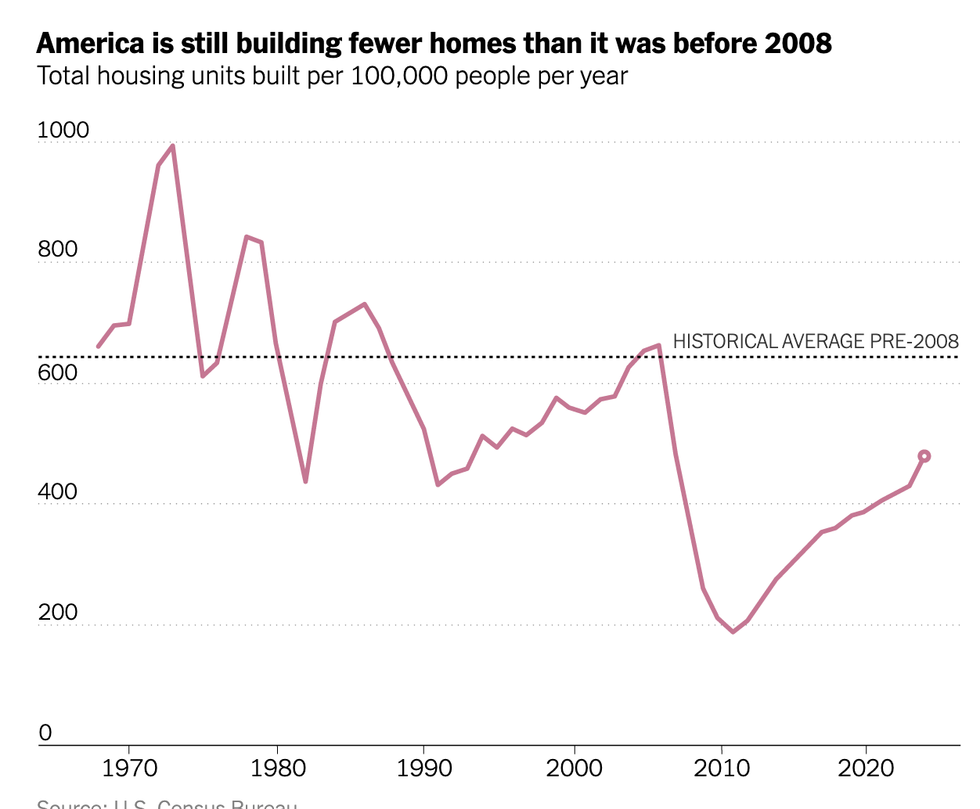

Ezra Klein had a classic column in the New York Times the other day which he advertises in its title: “America’s Housing Crisis, in One Chart.” The chart he highlights, new housing units per capita, is informative, but not quite in the way he says.

The chart shows the cyclical ups and downs in the housing market and then a massive plunge in construction following the collapse of the housing bubble in 2007-2008. Construction falls to one-third of the long period average by 2010. It gradually creeped up so that it was 75 percent of the long period average by the pandemic. It rose somewhat further after the start of the pandemic, fueled by low interest rates and increased demand.

Klein looks at his chart and sees massive underbuilding of housing, which he attributes primarily to excessive government restrictions on building, such as zoning and outdated safety requirements. I look at his chart and see the lasting devastation to the housing market that resulted from letting a bubble grow unchecked in the first decade of this century.

Asset Bubbles Are Bad News

While some of us were trying to warn of the risks of the bubble; the big names in economics (e.g. Alan Greenspan and Larry Summers) were singing the praises of innovative financing and the resulting increase in homeownership. When the bubble burst, not only did we get a financial crisis and the worst recession since the Great Depression; we also got long-lasting damage to the housing market that is still being felt today in the form of higher house sale prices and rents.

The reason for highlighting the impact of the bubble and its bursting, rather than the problems cited by Klein, is we need to have a sense of relative importance. Restrictive zoning is definitely a problem, and we should look at regulatory constraints, especially on manufactured housing, that may needlessly limit supply and push up prices.

But we had restrictive zoning and needless regulations before 2008 and still managed to build plenty of housing. That suggests that these are not the main obstacles to more construction.

The Collapsed Bubble Explains the Housing Construction Shortfall

In fact, if we look at Klein’s chart, it seems that most of the shortfall in housing, which he and others put at between 2-5 million units, was the result of the plunge in construction immediately after the collapse. Using 1.5 million units a year as a target for balancing the market (people are welcome to use a higher or lower one), we fell 6.4 million units short of needed construction levels in the decade from 2008-2017.

Construction has continued to climb upward in subsequent years so that in 2024 we were at 1.6 million completed units, somewhat above the 1.5 million target level used above. Construction will fall this year and next, as the rise in interest rates slowed starts, which will mean fewer completions in 2026.

This history doesn’t change the fact that housing costs too much and we need more construction, but it suggests that the problems may not be as deeply entrenched as Klein’s analysis implies. Rents and house sale prices were just moderately outpacing inflation until the pandemic.

When COVID hit, the pandemic relief packages put money in people’s pockets, at the same time the opportunity to work remotely expanded enormously. This both meant that people were saving money on commuting costs, which they could spend on housing, and that they needed more room at home to accommodate an office.

Those factors, together with low interest rates, led to a buying boom in 2021-22, and a surge in house sale prices. The Case-Shiller house price index rose by more than 50 percent in the five years from February 2020 to February 2025. Rents also surged, but not quite as dramatically.

Price and Rents Are Now Falling in Real Terms

But this was a one-time effect. With the number of people working remotely having stabilized, there is no longer a big surge in demand. The weakening economy also helps on this one. House sale prices have actually taken a modest downward turn since February, falling by almost 1.0 percent as of August. That translates into a 2.5 percent real decline, adjusting for inflation. It is likely this decline will continue and perhaps accelerate somewhat. (I am not anticipating the sort of collapse we saw in the 2008-2010 period, since homeowners are not heavily leveraged and in need of selling.)

There is also evidence that rents are falling, certainly in real terms and possibly also in nominal terms. The rent indexes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have a serious lag, reflecting long-term leases, but indexes that measure rents on units that come on the market are showing flat or declining prices. This is also the case with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ New Tenant Rent Index, which uses the CPI methodology, but only on units that come on the market.

This means that the problem of high housing costs may be correcting itself, but it would be good to hasten this process. Telling people that they have to wait three or four years for an apartment or house to become affordable is not a good story and certainly not good politics.

Reviewing safety regulations is definitely a good place to start. I’m less convinced on zoning. As much as it would be desirable to have denser housing in many areas, the politics of zoning are difficult, as Klein acknowledges.

The story also is rarely unambiguous. I am sure I will never be able to afford to live in San Francisco, but I still think that when I visit the city it is really neat to walk through neighborhoods filled with houses and small apartment buildings, constructed in the early part of the last century.

This is not just a personal preference. San Francisco has a huge tourism industry, as do New York and Paris and many other cities that have preserved a large portion of their past. It would be wrong to dismiss this preservation as simply selfish NIMBYism.

So, I would encourage efforts to reform zoning with the caution not to expect too much from them. (I will say that my friend Jared Bernstein’s proposal for a rent subsidy for high-cost cities taking steps to increase construction, which is endorsed by Klein, is almost certainly a political non-starter. It would imply transferring money from relatively poor red areas to relatively wealthy blue areas.)

Other Schemes

I would also throw in a few other ideas that could provide some modest short-term help. A progressive property tax that would, for example, have a higher marginal tax rate on homes that sell for more than twice the median in an area, would provide incentive for rich people to take up less space. It also has the advantage that assessed valuations are already on the books, so it requires no new administrative structure.

The same is true for vacant property taxes. This would provide disincentive for leaving units vacant. San Francisco and some other cities have already tried this policy. Even if this tax just leads many property owners to lie, it still raises the costs for them to have a vacant unit.

Incentives for converting office space to residential are also a good policy. Some office buildings are less well-suited for conversion than others. This means we want offices to move from the places that are easy to convert to the ones that are difficult. Government can help here.

And moderate rent control can be useful, especially as a short-term solution. There is also evidence that increased concentration in the construction industry following the collapse of the housing bubble has reduced building. This suggests that anti-trust policy may have a role to play in bringing down housing costs.

But the main point here is that the major shortage of housing the country faces now is not the result of zoning or regulatory obstacles but rather an overreaction to a collapsed bubble. Just as investors can be irrationally exuberant in driving a bubble, they also can be irrationally pessimistic in the wake of a collapse. It also didn’t help that the weak labor market coming out of the Great Recession meant that tens of millions of people didn’t have the regular income they needed to secure a mortgage. Also, millions had their credit ruined by a foreclosure after the crash.

All of this should just remind us that asset bubbles are not fun, at least not after they burst. We should remember this when we hear people singing the praises of AI.

Dean Baker is a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and the author of the 2016 book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. Please consider subscribing to his Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Dean Baker.