What’s the easiest and smartest thing a president could do right now to bring down drug prices? That’s easy. Allow quicker market entry for generic versions of biologics.

What’s the biggest thing the Trump administration has done in recent months to impact biologic prices? It made it far more difficult for biologic generics, better known as biosimilars, to enter the market.

How did that happen when the president is constantly using his Truth Social platform to brag about how much he’s doing to lower the price of drugs? He appointed leaders at the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) who are imposing policies that will make it far more difficult for biosimilar manufacturers to challenge improperly granted patents.

They are already allowing Big Pharma companies to maintain their illegitimate patent portfolios, known as patent thickets, which they use to deny market entry to cheap, generic competitors. These delays can last for years — even decades — beyond the expiration of an initial patent.

Why is this such a big deal and such a big gift to Big Pharma? While biologics make up only two to five percent of prescriptions (estimates vary), they generated around half of the pharmaceutical industry’s $634 billion in revenue in 2024. When still on patent, the price of individual biologic treatments can reach as high as several hundred thousand dollars per year. But when biosimilars enter the market, patients and their insurers save nearly 80 percent on average, according to a recent study in Health Affairs.

Before I get into the shenanigans at the PTO and how it will delay biosimilars, allow me to share some background for those not familiar with the complexities of the pharmaceutical industry and its biotechnology offspring, which was birthed by government-funded inventions that began in the mid-1970s.

Biologics are large organic molecules produced through genetic engineering that are usually delivered through injection or intravenous drips. Many of the greatest advances in drug therapy over the past half century have been through biologics.

The genomic revolution allowed scientists to replace proteins that patients’ bodies cannot produce because they have organ failure or genetic mutations. Genetic engineers also created monoclonal antibodies that target specific cancer mutations and the blood vessels that feed tumors. Vaccines are biologics. Scientists are now working on gene therapies that may permanently repair genetic birth defects.

Producers of biologics – like all drug makers – get patents on their inventions, a right guaranteed in the Constitution (thank you, James Madison) to promote innovation in “science and useful arts.” The idea was to create a limited period that incentivized creation of new inventions, but eventually ended so patent owners couldn’t use their patent monopoly to permanently levy exorbitant prices.

Patent terms have been changed repeatedly over the nation’s history. In 1994, Congress established a 20-year term for patents that began with the date of filing, an increase from the previous 17 years. In 2010 it added a 12-year guarantee of exclusivity to biologic manufacturers, whose products often remain in development for years after the initial patents are filed.

While that add-on was controversial, potential biosimilar manufacturers embraced the bill because it finally provided them with a pathway for entering the market. They also stood to benefit from the 2011 America Invents Act, which created a streamlined process at the PTO for challenging questionable patents. Instead of long and costly litigation in federal court, patent challenges would be heard by expert judges inside the PTO at a fraction of the cost. Appeals would be heard by an internal appeals board.

Information technology’s role

The impetus for the streamlined challenge process came from leading information technology firms (Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc.) who were being besieged by so-called patent trolls, who would buy or write patents they never intended to use that were similar to cutting edge info-tech technologies. The trolls, often backed by private equity investors, used those patents to file patent infringement lawsuits against well-heeled high-tech firms who had actually developed, patented, and used similar technologies. The goal: To extract huge settlements through patent purchases or licensing fees.

One major user of the new challenge process, called inter partes reviews (IPRs), turned out to be biosimilar manufacturers, who wanted a faster and cheaper way to challenge the patent thickets being erected by Big Pharma and biotech firms. Virtually every company that produces FDA-approved biologics and small molecule drugs (pills and capsules) files follow-on patents at the PTO. Any individual product may win a dozen or more, usually involving small changes in dosages, formulations or routes of administration.

“By creating large patent portfolios, companies can make it more difficult for competitors to enter the market by increasing transaction costs and/or delaying US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval,” law professors Sean Tu of the University of Alabama and Ana Santos Rutschman of Villanova University wrote this month in JAMA Health Forum. “Patent thickets can also be leveraged to force competitors to settle litigation, thus delaying market entry, or to enter under unfavorable conditions (such as restricted volume entry).”

One study they cited showed 78 percent of all “new” drug patents are part of a post-approval patent thicket for an already approved drug. This tactic has slowed adoption of biosimilars to a crawl. Fifteen years after passage of the law creating a pathway for biosimilar market entry, there are still fewer than 50 on the market, despite there being over 600 FDA-approved biologics, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines, the trade group for biosimilar manufacturers.

The process sped up during the Biden administration as biosimilar manufacturers increasingly turned to the IPR process to challenge questionable patents. They were aided by the fact that the administrative process at the PTO takes only 12 months and costs about $725,000, according to another recent paper co-authored by Tu. Patent litigation in federal court, by contrast, costs on average over $6 million and takes years to resolve.

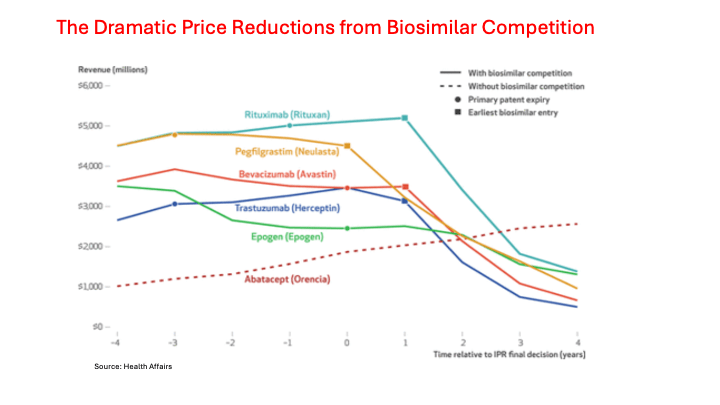

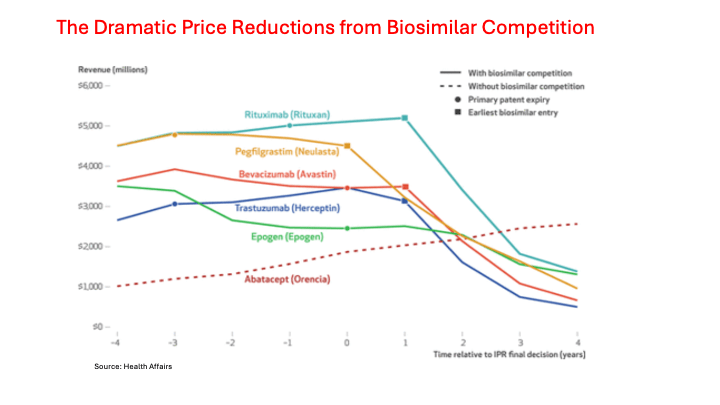

Biosimilar manufacturers started racking up an impressive IPR win rate at the PTO. Another recent study showed biosimilar manufacturers won 14 of 20 challenges that were holding up market entry for their products. They eventually won FDA approval and saved patients and their insurers tens of billions of dollars. Five are shown in the following chart.

(Note: The bottom scale (-4 to 4) represents the years before and after a biosimilar manufacturer won a patent invalidation case at the PTO. The solid lines represent five of the more expensive biologics that lost exclusivity over the past decade. In each case, the sharp drop in revenue due to lost sales to biosimilars didn’t show up until a year after the PTO ruled because the Big Pharma firm defending the patents had a year to appeal. The bottom dotted line shows how one representative biologic that didn’t face biosimilar competition more than doubled its revenue over a similar time period.)

Big changes at PTO

But the PTO reversed field this year. PTO acting director Coke Morgan Stewart, who had worked at PTO during the first Trump administration before joining O’Melveny & Myers, a major corporate law firm, began using a process she dubbed “discretionary denial” to block patent challenges. In 2024, the patent appeals board had approved nearly 75 percent of all patent challenges. By September of this year, the first under Trump, that rate had declined to 35 percent, according to another study by Tu, this time with Arti Rai of Duke University and Aaron Kesselheim of Harvard Medical School.

The scholars reviewed Stewart’s decisions and found she had created a novel rationale for dismissing patent challenges. She argued that after six years (about the average age for drug patents being challenged), the patent holder should expect they will no longer be administratively challenged. “Before 2025, the ‘settled expectations’ rationale never even existed,” Tu and his colleagues wrote. “It now accounts for a large percentage of denials and is even used when administrative review petitions raise reasonable technical grounds for invalidation.”

In September, the Senate approved John Squires to run the PTO, though he is not a registered patent attorney. He did chair the Emerging Companies and Intellectual Property practice at Dilworth Paxson LLP in Washington where he represented numerous AI, blockchain, crypto, and financial technology companies. He also made campaign contributions to both of Donald Trump’s victorious election campaigns and more recently to the Never Surrender PAC, which is one of the president’s vehicles for supporting GOP candidates in the 2026 mid-term elections.

One of Squires’ first acts after winning Senate approval was to centralize the IPR decision-making process in the director’s office, thus removing it from the experts who understood the technical issues. He also limited the length of briefs that petitioners could file. Then, in mid-October, Squires announced that “he would personally decide every IPR proceeding,” which cannot be reviewed judicially. He also declared he could issue “summary notices,” that may include little or no explanation for denials.

“By aggressively invoking discretionary denials, the USPTO is subverting an important administrative pathway that Congress specifically created to check weak patents,” Tu, Rai and Kesselheim wrote. Seven lawsuits have already been filed challenging the new policy. They call on Congress to “step in” and “explicitly prohibit denials based on non-merit-based criteria such as ‘settled expectations’.”

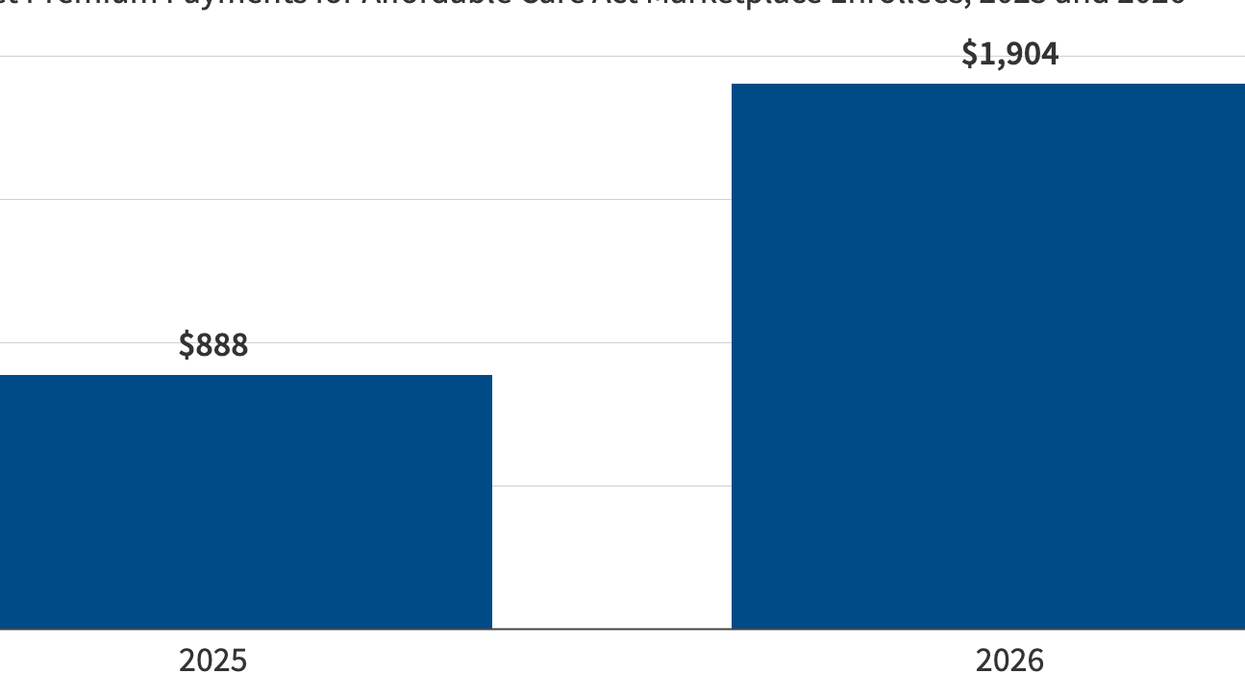

This Congress? Fat chance. Look for a dramatic slowdown in the pace of biosimilar adoption over the next few years and for a continuing sharp rise in consumer and payer spending on biologics, the most expensive drugs on the market.

Merrill Goozner, the former editor of Modern Healthcare, writes about health care and politics at GoozNews.substack.com, where this column first appeared. Please consider subscribing to support his work.

Reprinted with permission from Gooz News

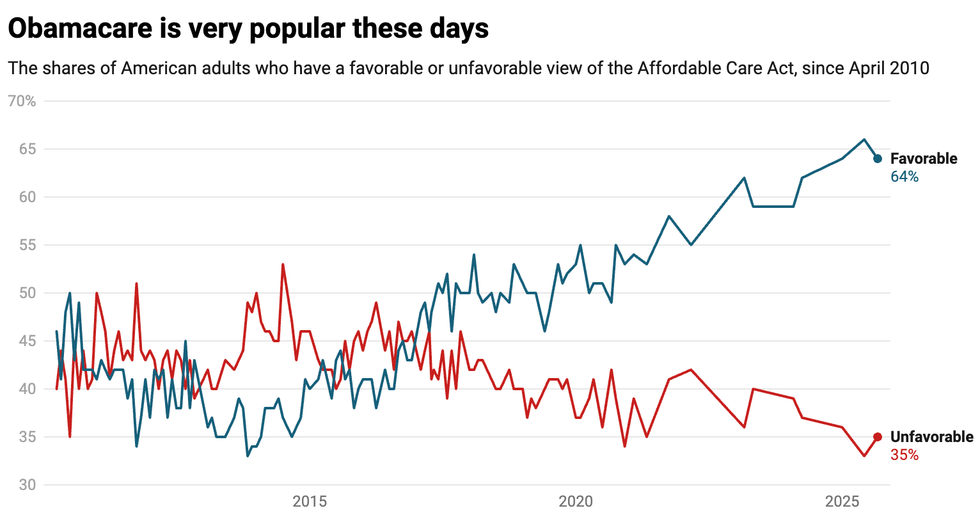

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation