Democracy Needs A Stronger Labor Movement -- And Americans Can Build It

A few weeks ago, I interviewed John Cassidy, the New Yorker economics writer, on his latest book, Capitalism and Its Critics, which I also reviewed. I found the book to be an elucidating and well-timed look at our economic system through the eyes of capitalism’s founders, scholars, critics, and revolutionary opponents. Reading this sweeping treatment in 2025, I believed that it carried a important lesson from history as to how we got into our current mess and how to get out of it.

Towards the end of our interview, I asked John about this, and I found his answer highly resonant. We had been talking about Karl Polanyi’s concept of the “double movement,” which observes that throughout history, the push and pull of capitalism’s destructive tendencies have been offset by measures to temper such outcomes. Polanyi, a socialist who witnessed the rise of fascism, argued that without a movement to counterbalance capitalism’s inevitable trajectory towards concentrated resources and power, societies would devolve into the highly unequal, inhumane, and violent state that Polanyi himself observed in Europe in the 1930s and 40s.

Throughout history—with tragic exceptions—when the system drifted too far one way, pressure from below would push back on its hard edges through the introduction of measures like social insurance (against old-age, ill-health, unemployment), job protections, wage policies, and so on.

When I asked John about this in the current context, he said (lightly edited):

You need a political basis for any sort of lasting economic movement. And I think that's the great challenge we face now, because back in the mid-century, there was a pretty clear blueprint based on the labor movement.

The pressure came from below, but where was that pressure coming from?

It was coming from workers and the labor unions, which were very strong in the U.S., the famous Treaty of Detroit, etc., very strong in the U.K., the labor movement, the Labor Party. Same in Germany, same in France. How do you create a political movement to sort of underpin a new social bargain when you don't have a strong labor movement? That seems to me to be the central question, the sort of left, center-left, even the center, is facing in the 21st century. And I don't think we've answered it yet. I mean, Trump has got an answer. He has a movement, whatever you think of him. He has a popular movement, and he has a very simplistic economic nationalism.

Especially on Labor Day, we often think of unions as getting a better deal for their members, ensuring that they get a fairer slice of the pie they’re helping to bake. And that’s of course unquestionably the case: labor unions first responsibility is to improve the living standards of their members by improving the quality—compensation, benefits, working conditions—of their jobs. And the evidence across time and place shows that they do so.

But that’s not all they do.

There is copious analysis as to how populists—in Trump’s case, a faux populist—ascend to power. One explanation is that the labor-left party drifts right, captured by the same deep-pocketed donors that bankroll the conservative party and abandoning or ignoring the plight of the working class. Much like nature, politics abhors a vacuum, which in this case gets filled by a populist, who promises to re-elevate and address the economic concerns of the working class.

As always, nuance abounds. From the 1970s to Trump, it wasn’t that Democrats stopped opposing Republicans. But the focus shifted from the working class and the poor to just the poor. Bill Clinton was notoriously indifferent at best towards unions, especially as they fought him, unsuccessfully, on NAFTA and China’s joining the World Trade Organization, which they did to protect their constituents from competition with cheaper labor and the loss of manufacturing jobs. But Clinton also presided over the largest poverty-reducing expansion on record of refundable (meaning you get the credits even if you have no tax liability) tax credits for low-income workers (which itself was in part a response to his poverty-increasing “welfare reform”).

The working class was then left to fight it out on their own as they were thrown into global competition with much lower-wage countries. The minimum wage went on a long-slide, with insufficiently small adjustments (all by Ds, of course, including Clinton). Labor standards and protections came to be viewed by members of both parties as “rent-seeking” by workers and thereby antithetical to growth and innovation. Unions went from being viewed as a crucial partner in Democratic politics to a hindrance at best and at worst, a barrier to globalization and the power of unfettered markets.

And anyway, many high-ranking Ds thought at the time, where are they gonna go? (Not all Ds, to be clear; I admit to painting with a broad brush but I believe I’m painting the right picture). As Ds became disengaged with the unions, and certainly didn’t fight to stop their decline, they assumed that when push came to shove, they’d have their remaining votes, which turned out to be a consequential miscalculation.

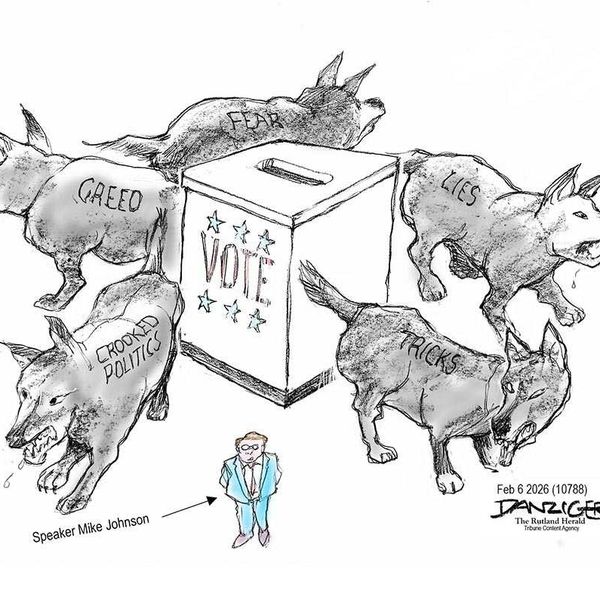

This was a huge blow to the double movement, essentially taking the pressure-from-below off of the field. The result was the absence of a countervailing force, an organized workers’ movement to block the rise of a phony populist whose blatantly empty promises went largely unchallenged.

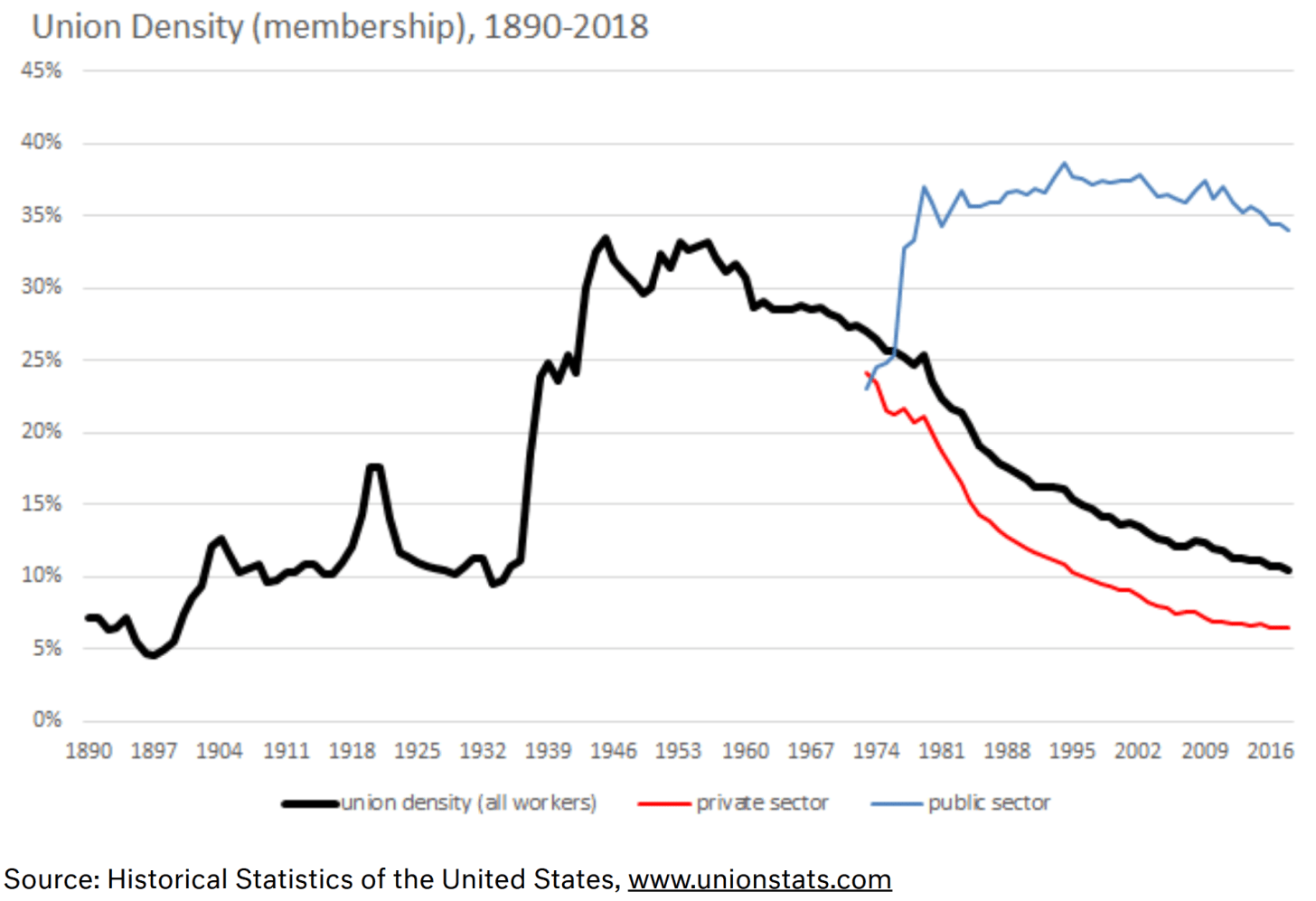

At this point, union coverage is around 10% in the U.S., though much higher in the public than the private sector (the figure below ends in 2018 but that’s still around where we are), and much lower than in most of Europe and especially in Scandinavia, where labor’s role in double movement has been especially powerful.

But what are the chances of a revived labor movement? If that’s what it takes to bring back pressure from below, we’re toast, right?

Wrong!

First, look at what happened in 1932 when union membership jumped more than 3-fold. Yes, it was the Great Depression, a massive failure of capitalism that laid bare what can happen when capital is unconstrained, thereby heralding in a strong counter-movement. But more than that, it was policy, including the National Industrial Recovery Act and the National Labor Relations Act, which, for the first time in our nation, created the legal framework supporting unionization.

In our context, it was a moment when government was forced to acknowledge and address the fact that absent pressure from below, pressure from above would break the system. And the legislation that followed unleashed strong, untapped demand for union coverage.

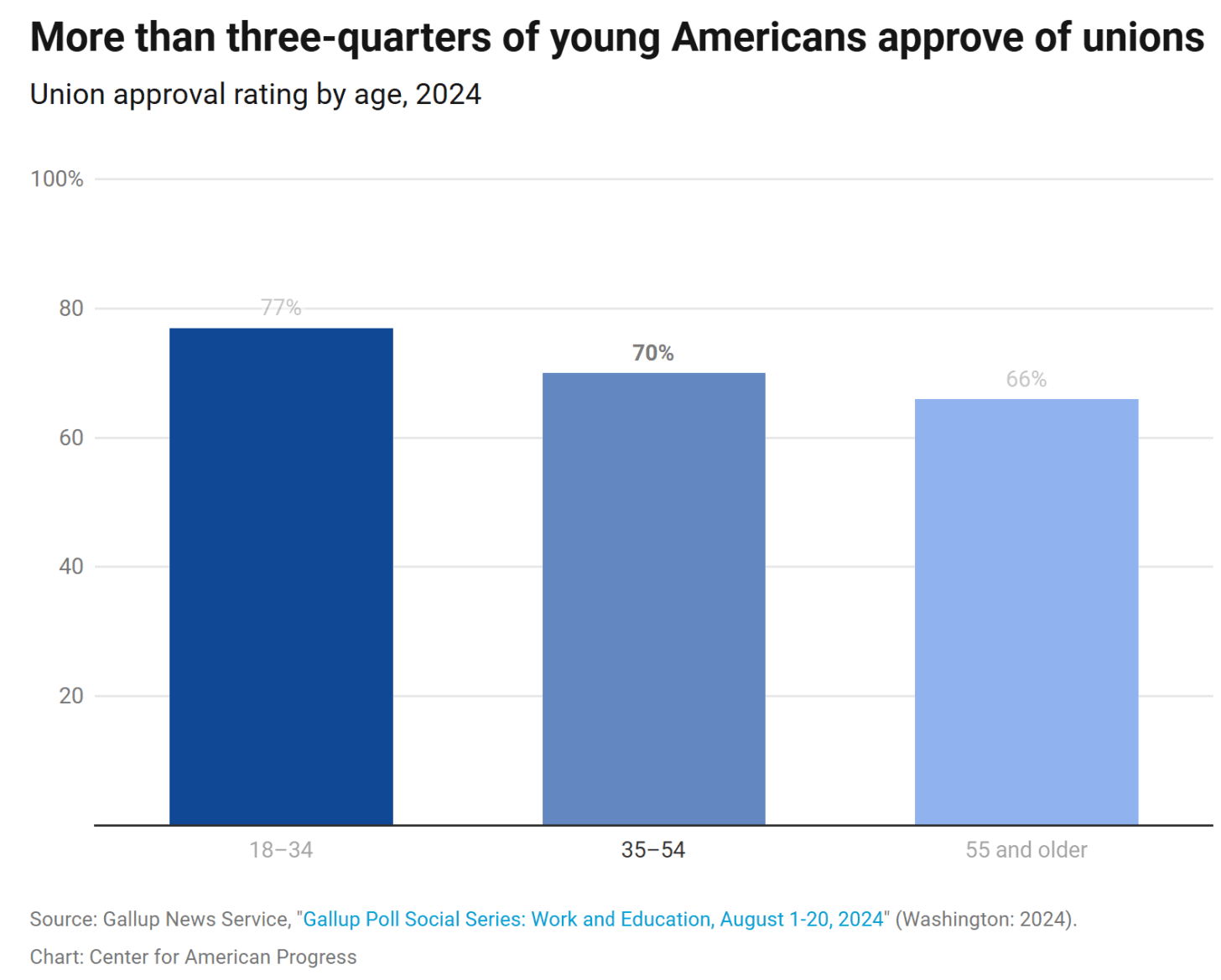

The thing is, that same untapped demand exists today. EPI points out that “in 2023, [when about 16 million workers were covered] more than 60 million workers wanted to join a union but couldn’t do so.” The figure below, from the Center for American Progress’ American Worker Project (a deep resource for this information), shows that union approval in public opinion ranges from two-thirds to three-quarters. Again, as these links make clear, the gap between demand for union coverage and its supply is a policy problem. The playing field is tilted against union organizing, such that in bargain-power conflicts between labor and capital, labor’s fighting with an anvil around its neck.

Look at the public sector line in the first figure above. The big difference there is that the process of forming and building public-sector unions is far more legally protected than in the private sector, where there’s virtually no penalty for blocking unions’ efforts to organize, even when such blockage violates standing labor laws. The links above explain policy proposals like the PRO Act, designed to remove these blockages, giving workers the chance they’ve long lacked to pursue their legal right to union coverage.

All of which leads to my Labor Day message. History is clear that capitalism remains a highly effective system of generating growth and technological gains. But without an organized and aptly sized political counterforce, it will concentrate wealth and power in ways that will leave huge swaths of the population behind and erode the guardrails that are essential for containing the system’s excesses.

That is where we are now, and a major reason for that, as John points out, is that the size and power of the labor movement, a force that has throughout history played this role, is insufficient.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that there is a strong demand to rebalance this skewed power imbalance, a demand that’s growing as Trump continues to build on and abuse the power of the presidency in ways that redound against the very working class he claimed he’d help. And there are policies to tap that demand.

Even without a much stronger labor movement, anti-incumbency and the sheer incompetence of the current administration may bring them down. But that’s not good enough as recent history suggests it just means we keep swinging back-and-forth from one side to other, with no foundation upon which to build a lasting coalition for economic justice and balanced power.

That foundation requires a strong labor movement and it is well within our grasp to build it.

Jared Bernstein is a former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Joe Biden. He is a senior fellow at the Council on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Reprinted with permission from Jared's Substack. Please consider subscribing.