Why That 'Miranda' Warning Matters So Much Less Than You Think

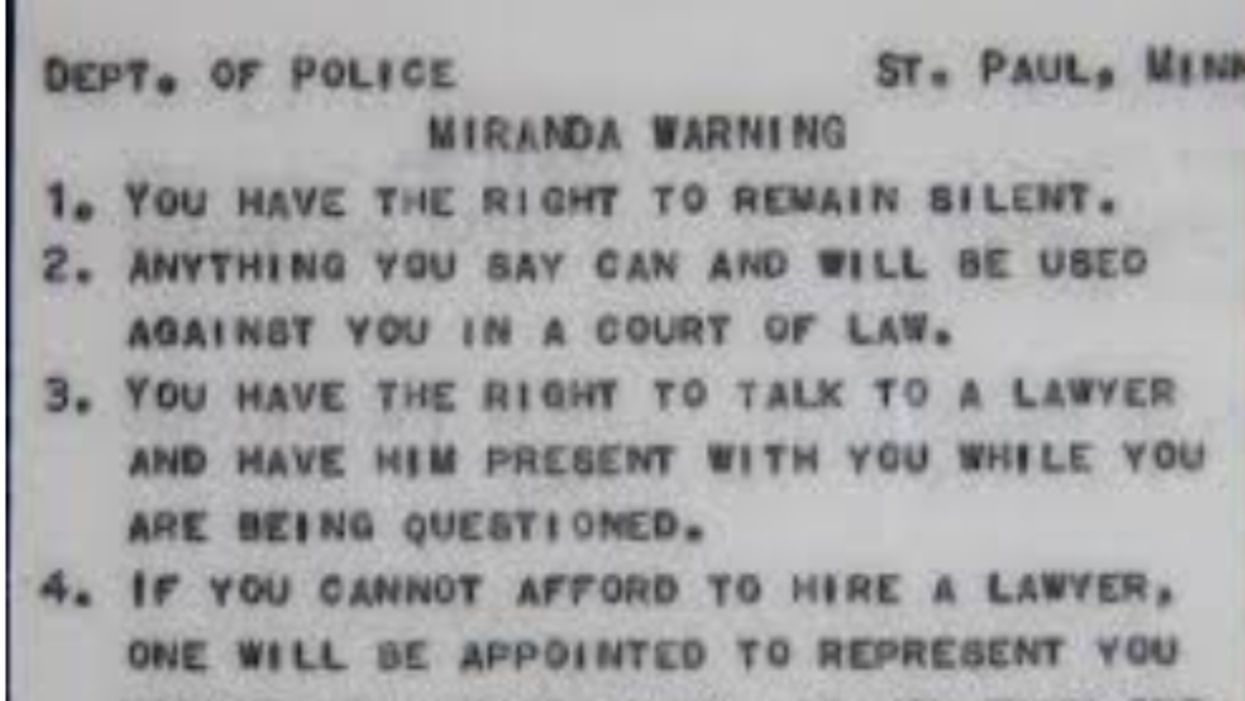

The United States Supreme Court decision in Vega v. Tekoh, released on June 23, worries many constitutional rights experts. Once the Clerk of the Court released the opinion, the digital town square grew rife with nervous energy that the Miranda warning -- the legally mandated reading of rights by police to suspects to inform them of their Fifth and Sixth Amendment protections while in custody -- is all but gone.

Graydon Gordion, a member of the executive board of the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia tweeted: “Roe. Miranda. Gun control. Church and State. All dismantled in a single week. The single worst week for civil rights and liberties in decades.”

Elie Mystal, attorney and justice correspondent for The Nation chimed in on the bird app, too, in partial accuracy. “Folks,” Mystal wrote, “this basically overturns ‘the right to remain silent.’”

Colin Kalmbacher, editor of Law and Crime News, described the decision this way: “U.S. Supreme Court conservatives overturn time-honored Miranda rights in landmark decision."

But I’m not that worried. All the new decision says is that law enforcement’s failure to Mirandize — meaning read the warning and a list of their Fifths and Sixths as outlined by the Supreme Court in a 1966 case called Miranda v. Arizona — doesn't afford a suspect any remedy under the federal civil rights code. Miranda lives on.

And that’s the problem because Miranda is a mirage; the warning ritual creates the appearance of protecting a suspect’s constitutional rights but doesn’t really do the job.

Miranda’s job, of course, is to protect people from coercive police tactics and misinterpretation of their protestations of innocence; the warning isn’t designed to provide refuge for the guilty, which is the main criticism of the constitutional right. False confessions happen only when a suspect is communicating with law enforcement. Those words that can and will be used against you in a court of law only exist if you utter them.

Or so the public thinks.

Let me tell you a story called State of Connecticut v. Chandra Bozelko. Picture it: Milford, Connecticut, 2007. It was a sunny October afternoon outside 14 West River Street, but inside, my future looked forbidding as the Assistant Chief of Police of the Town of Orange, Connecticut sat on the witness stand describing my arrest on February 2, 2005 for various crimes related to credit card fraud. In a nutshell, packages with purchases made on others’ credit card accounts had been directed to my parents’ home in Orange. They arrested me for various offenses and then went about trying to connect me to the crimes.

“At that point,” Koether said, “I read her her rights from a little rights card and asked her if she would talk to me.”

After officers transferred me to the station and I signed the paper acknowledging my advisement of rights, I asked to speak to my lawyer. When asked whom to call, I gave an officer my sister’s and my father’s numbers. They were both lawyers. I spoke to both of them and, as they arranged to post bond for me, I sat in one of the Town of Orange’s holding cells, alone, talking to no one.

The police said I confessed anyway.

The very next day in the trial, then-Officer Robert Cole (he went to another department in 2016 where AAA recognized him for his superior traffic enforcement) — falsely testified that I confessed to procuring other people’s credit card information and using it.

Cole swore under oath that I unburdened myself to him and divulged that someone called me on the phone and provided me with the stolen credit card numbers. That’s how I pulled off this massive attempted heist, according to Cole: I just answered the phone and a third party -- a person whom the police never even attempted to identify and have no idea who this person was -- provided me with stolen credit card information, an act that would have positioned as him my accomplice, as well as made him even more of a risk to the community than I since he was grabbing personal financial information from unsuspecting marks.

It should go without saying that this alleged confession doesn’t make sense - unless law enforcement traced calls to my phone and identified this caller, which they never tried to do. And, of course, the prosecution introduced no written, audio, or video memorialization of this alleged confession — because they were never required to do so.

The Innocence Project lists Connecticut as one of 30 states that require recording of certain custodial interviews but that inclusion isn’t entirely accurate. The Supreme Court of the State of Connecticut held that the state constitution doesn’t require recording of interviews. Memorialization is required only if certain circumstances apply.

No confession that isn’t memorialized in writing, audio, or video should even merit consideration as evidence in a criminal trial, much less get introduced into the record. But they do. These bogus unbosomings underwrite many convictions.

So Miranda warnings may be talismanic to civil rights advocates but they’re often useless in my opinion. I was read my rights, exercised them, and said nothing -- and yet the cops still boned me with a false confession I didn’t even make.

Miranda’s better half -- my right to counsel and her effective assistance to me -- was supposed to provide some adversarial testing to this Fifth Amendment fracas. But that didn’t work out either.

When Officer Cole described this alleged confession, one he had mentioned in a police report, my attorney, Angelica Papastavros, asked for the proof. It’s not clear that she understood that police don’t have to record or memorialize anything but she said she’d never heard of this alleged confession, that no one had provided it to her in discovery. It would have been a valiant defense if she hadn’t been holding the document in her hand when she made the argument.

“You do recognize the fact that you do have that document?” the judge asked her.

“So far, nothing rings a bell,” she replied.

The false confession didn’t ring a bell because my attorney hadn’t actually read the case file, the papers in her hand, before trial. She could have filed a motion to suppress the nonsensical confession or to hold a hearing on why, if the police accepted the cockamamie explanation that a random, unknown person plied me with stolen credit card numbers over the phone, none of them ever traced the calls to that line to identify that person. No one tracked down the mystery caller, most likely because he never existed, along with the confession, not that the record indicates any of that. It’s hardly a surprise marshals carted me to the state’s only women’s prison two months later.

Even leaving my story out, scant evidence supports Miranda’s effectiveness. People who know their rights still think that talking to police is wise if they’re innocent; most of them are juveniles or adults with mental health problems. If Miranda did her job, the number of false confessions would have dropped after 1966, when the warning became required by law. But they didn’t.

All the false confessions identified by the National Registry of Exonerations between 1989 and 2016 were squeezed out after a Miranda warning. Studies show that recitation of rights doesn’t effectively inform suspects with language barriers. Miranda’s a mess.

The moral of this story is that Miranda isn’t what people think it is; silence doesn’t even guarantee that police won’t say a suspect confessed. Not only should anyone in custody remain silent and ask for counsel, but that person shouldn’t even agree that they’ve been read their rights. Acknowledging a Miranda warning makes it easy for police to construct a narrative, as I learned entirely too well.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.