For Prisoners, Medicaid Waivers Permit Off-Site Care -- And Better Outcomes

Lidia Lech reached for a ramen noodle container because that’s all she had to contain the green-brown discharge coming out of her vagina.

She planned to show it to a doctor at Baystate Medical Center and ask them if it indicated any danger to her unborn son, Kaiden, whose Caesarian section delivery was scheduled for January 15, 2014.

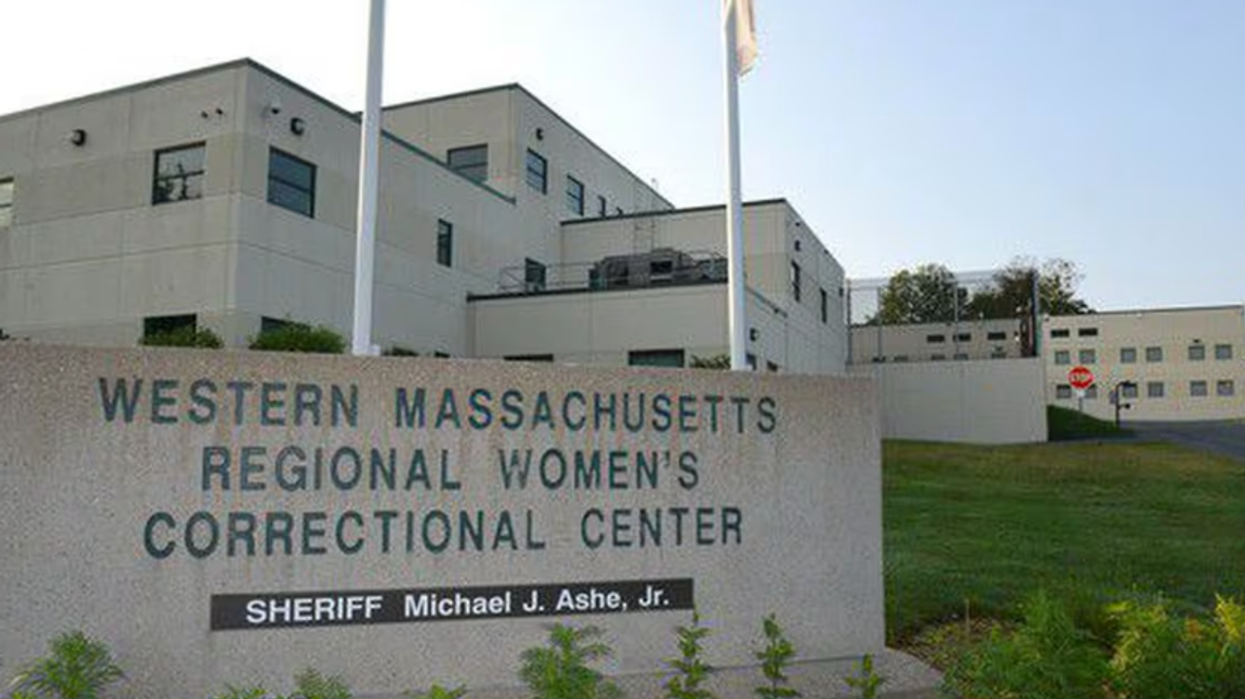

Incarcerated at the Hampden County Sheriff's Department’s Western Massachusetts Women's Correctional Center ("WCC") in Chicopee, Massachusetts, Lech had been told what she already knew at an intake assessment months earlier: that she was carrying a high-risk pregnancy. Six years earlier, she had lost a baby to a uterine rupture.

It was two days before Christmas and she had spent the months of November and December pleading for medical attention, to be transported to Baystate again. An ultrasound had been conducted at the hospital days on December 18 and doctors told her that her baby was fine. But she didn’t agree. Something was wrong.

To the nurses at WCC, Lech reported all of her symptoms: a list that kept growing and looking like a list of conditions that require immediate attention when a woman is less than 37 weeks pregnant: a rash, itching in her vaginal area, pain, a racing heart, severe headache, changes in eyesight. blurred vision, feeling her son Kaiden kick less often, vaginal bleeding, preterm uterine contractions, and the discharge she stored in the ramen cup. Certainly, that type of discharge wasn’t normal.

'The Nurses Need To Know If This Can Wait 'Til Morning'

Each time, nurses told Lech to lie on her side and drink water -- when they were in the office. That year, Christmas landed on a Wednesday. It would be one of those holidays where the whole week slides into inertia as people take off the Monday before Christmas Eve to round out their weekend or the two days after Christmas to extend a New Year’s vacation.

Over the next several days, Lech would puncture those two weeks of holiday-level staffing by approaching guards — to let her go to the medical office — and nurses when she managed to reach them, and bringing the cup with her whenever she asked to see the medical unit to show them her concerns.

Then they turned up the pressure to keep Lech away. Nurses called her ‘overbearing” and told her she’d make a terrible mother.

On January 1, 2014, during a head count, Lech felt fluid gush between her legs and severe cramping doubled her over. She called for help through the intercom in her cell and a guard responded that she needed to wait until counting was over.

The guard rang back in when the count had cleared, asking:

“How bad are your symptoms? The nurses need to know if this can wait ‘til morning.”

Lech’s cellmate started screaming. Another fifteen minutes later, the clack of the cell door unlocking signaled to Lech that she could now leave and head over to the medical unit. Even though she struggled to walk, no one sent a wheelchair to bring her to the unit. At the unit, she waited another hour, muttering “He’s gone, He’s gone.” Again, nurses refused to send her to Baystate — until they tried to monitor her son’s fetal heartrate and could detect only hers.

Her son Kaiden was stillborn on January 2, 2014. His body was macerated which meant that he had already died, an unknown number of days prior.

Prisons and jails are prisons and jails. Although they’ve been called de facto hospitals as part of the criticism of policies that contribute to mass incarceration, they are not designed to provide medical care, certainly not the care that a high-risk pregnant woman needs.

As much as 40 percent of a corrections budget is for care provided outside the prison or jail according to analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Vera Institute of Justice.

The only way to access that outside care is for someone at the correctional facility to agree that the detainee needs care that’s not available in the facility; inmates can’t access these resources on their own.

Off-site services supplement on-site care which is delivered through one of four systems: direct model (state and municipality-employed corrections department clinicians provide all or most on-site care); contracted model (clinicians employed by one or more private companies deliver all or most on-site care); state university model (the state’s public medical school or affiliated organization is responsible for all or most on-site care); and the hybrid model (on-site care is delivered by some combination of the other models). States and municipalities vary in the methods and often change them; monitoring the delivery methods of all state prisons and municipal jails is next to impossible.

Depending on the model of on-site care, the role and responsibilities of the person who approves a detainee for off-site care changes.

Medicaid coverage changes the incentives and realities in off-site correctional healthcare. Since the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP) was established in 1965, Medicaid has been allowed to cover the costs of inmate inpatient hospitalizations that last more than 24 hours. Jails and prisons can save money if they can arrange for their wards to be treated at local hospitals — if they’re willing to risk the cost of the consult.

Matthew Loflin was arrested for drug possession in Savannah, Georgia around the same time that Lidia Lech lost her son nine states to the north. Symptoms for his cardiomyopathy crept up on the 32-year-old man while he awaited trial in the Chatham County Detention Center. He was coughing, often to the point of blacking out.

Despite the jail doctor’s recommendation, none of the empowered decision-makers at the facility— which contracted with Corizon for care — would let Loflin be seen at the hospital, even though the likelihood that he would be admitted was high. Medicaid would pick up that tab, if he were to reach a hospital. He didn’t, at least not in time. He died in April 2014.

“The for-profit medical provider had no intentions of treating him because cardiology appointments outside of the jail would cut into their profit margin. One of his jailers called his pain and anguish ‘fussy,’” Loflin’s mother Belinda Maley told the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in September 2022 when it held a hearing on unreported jail and prison deaths.

Loflin was admitted on an inpatient basis, making his death even more senseless. But not all incarcerated patients are admitted; the decision to admit a patient is entrusted to the hospital staff. So a referring agency takes a risk by sending one of its wards to a specialist or hospital. If the detainee is admitted, then the hospital can submit a bill to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and expect reimbursement.However, if the attending physicians decide not to admit the patient and the patient is there for less than 24 hours, then the jail or prison has incurred a bill. One sheriff of a county in Florida agreed to discuss this matter on the condition of anonymity. He said: “I won’t lie. Whether one of our inmates is sick enough to be admitted is a big factor in our decision to send them to a local hospital for evaluation or treatment. The thing is, neither [I] nor any of my deputies know how sick an inmate really is. But we are mindful that, if they get sent right back to us, we’re going to be paying thousands for that trip.”

And it’s not always the case that local hospitals welcome these patients. Off-site care is wracked with security concerns that usual prison/jail healthcare is not in that it brings someone who is in the physical and legal custody of the government into a setting that is not designed for that custody.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics doesn’t track the site of escapes from correctional custody; the agency only counts the events where someone leaves custody illegally. It should surprise no one that most escapes occur from hospitals or transport to medical appointments that aren’t in the correctional facility. During the past summer, seven people escaped from custody from medical establishments between August and October.When interests are aligned, as they are in systems where the state university medical system provides care in correctional facilites, Medicaid coverage can improve outcomes for prisoners.

Lynn W. (her last name is being withheld for privacy reasons) was diagnosed with breast cancer while she was incarcerated at York Correctional Institution in Niantic, Connecticut. To receive the chemotherapy she needed, she had to go to the UCONN Medical Center in Farmington every weekday.

She made the 54-mile trip by traveling with the women who were due in court that day. She would wait to board a bus in freezing, predawn temperatures without a coat (not allowed on transport). Corrections officers would drive them, handcuffed and shackled, to the Hartford Police Department. From there, officers from the prison unit at the John Dempsey Hospital (the University of Connecticut’s hospital) would pick her up from the police station and bring her and any other women with appointments at UCONN that day to the hospital.

After these appointments, the same guards would return the women to the Hartford Police Department where they would await all other women who appeared in court that day — and the women who were newly remanded to custody — and, as a group, they would pass the time until the York guards came back, cuffed and shackled them and drove a bus (or two) with all of them back to the prison. Sometimes they didn’t return to York Correctional Institution until 11 p.m. — and Lynn would be woken at 3:30 a.m. the next day to start the process all over again

One day, she told her oncologist she was quitting.

“I don’t want the chemo anymore,” she said.

“Why?” he asked her. “This particular treatment works well with your cancer. I’m hopeful that after a few weeks of this, your cancer will be gone forever. Remission. Why would you stop it now? Is it the side effects?”

“No, it’s the ride. I haven’t slept more than two hours a night since we started. Even if you cure my cancer, I’ll be dead anyway.” She proceeded to explain the process of getting off-site care.

After a quick call from her oncologist, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid approved Lynn’s inpatient stay. The doctor broke the news to the medical office at the prison.

“She’s not coming back,” he told the nurses in the medical unit. He didn’t mean she would die. He meant she would live, stay at the hospital while she received the full course of treatment. Connecticut is one of three states that use a state university model. Lynn slept even better than she would have in the prison, and was returned to custody.

Lynn is home today, married, and working. Her breast cancer has been in remission since 2011.

Hospitals And Jails Are 'Insurance-Free Zones'

Jails are filled with low-income people who can’t afford to post bond. Two-thirds of people detained in jails report annual incomes under $12,000 prior to arrest. Despite the thoroughness of the indigency of an incarcerated population, in Washington State, jails are required to gather information about the person’s ability to pay for medical care as part of the intake process, including whether the person has insurance. Additionally, at sentencing, courts are authorized to require an individual to repay their medical costs based on their ability to pay.

Ever since January 1, 2014, when the Affordable Care Act required all Americans to have health insurance coverage through the individual mandate and permitted “all qualified individuals” to purchase qualified health plans through their state’s health insurance exchange, inquiry about an individual’s ability to pay their medical costs while incarcerated has become a part of the sentencing process in many jurisdictions.

It’s a futile inquiry; prisons and jails are insurance-free zones. Exchanges don’t permit prisoners to apply for coverage. Even if they apply, secure approval for, and purchase a plan to use during a short term of incarceration, the providers in prisons and jails aren’t in insurance networks. Incarcerated patients not only lack the freedom to choose providers, make appointments, and enter a medical office, they have no way to cover the care they need. They are at the mercy of decision-makers who often have different agendas regarding their health.

That complete lack of insurance coverage shows where correctional healthcare intersects with “legal financial obligations” or LFO’s, the aspects of prosecution and incarceration that prisoners have to pay for themselves. Even the Fines and Fees Justice Center (FFJC), an organization dedicated to stopping the overuse of fines and fees does not know which states would consider medical care an LFO.

'How Can A Medical Debt Become A Jail Debt?'

Very recently, medical debt almost became an LFO.An infection was all that Robert Lambert had. At home, he would have gone to a local pharmacy and purchased a few items to see what worked. If it got worse, he’d ask friends and family for advice.

But he couldn’t do that. He was in Kittitas County Corrections Center (KCCC) awaiting disposition of his charges. He asked to be seen at “Sick Call,” the medical unit’s office hours; detainees need to wait to be called. They can’t attend at will. Getting to see a provider in KCCC was difficult for Lambert. At the time, the county contracted with Comprehensive HealthCare for a nurse to be on site for three hours every other Thursday, approximately six hours per month, less than one workday, to meet the healthcare needs of around 200 people.

It took so long to get to Sick Call that Lambert’s infection worsened. He was brought to Kittitas Valley Hospital (KVH) every day for days for intravenous antibiotic treatment to kill the infection, the bill for which was $21,152.8. KVH discounted its services by 46 percent, down to $11,422.52. It was a large invoice to be paid, and also likely an unnecessary one if Lambert had received care in a timely fashion.

KCCC officials shoved a stack of receipts (not a detailed medical record) and claimed he owed the jail $11,422.52, the same amount KCCC had paid the hospital. On the day that Lambert was to discharge, the jail added $1398.07 in interest to the bill, making the total owed $12,820.59. He looked at his inmate account, the funds he used to buy commissary.$0.02, it read.

“Like many other people in jail, I didn’t have a job, I didn’t have savings, I didn’t have any way to even make small payments on that amount they said I owed,” Lambert said. To make matters worse, the jail sent the bill for collection.