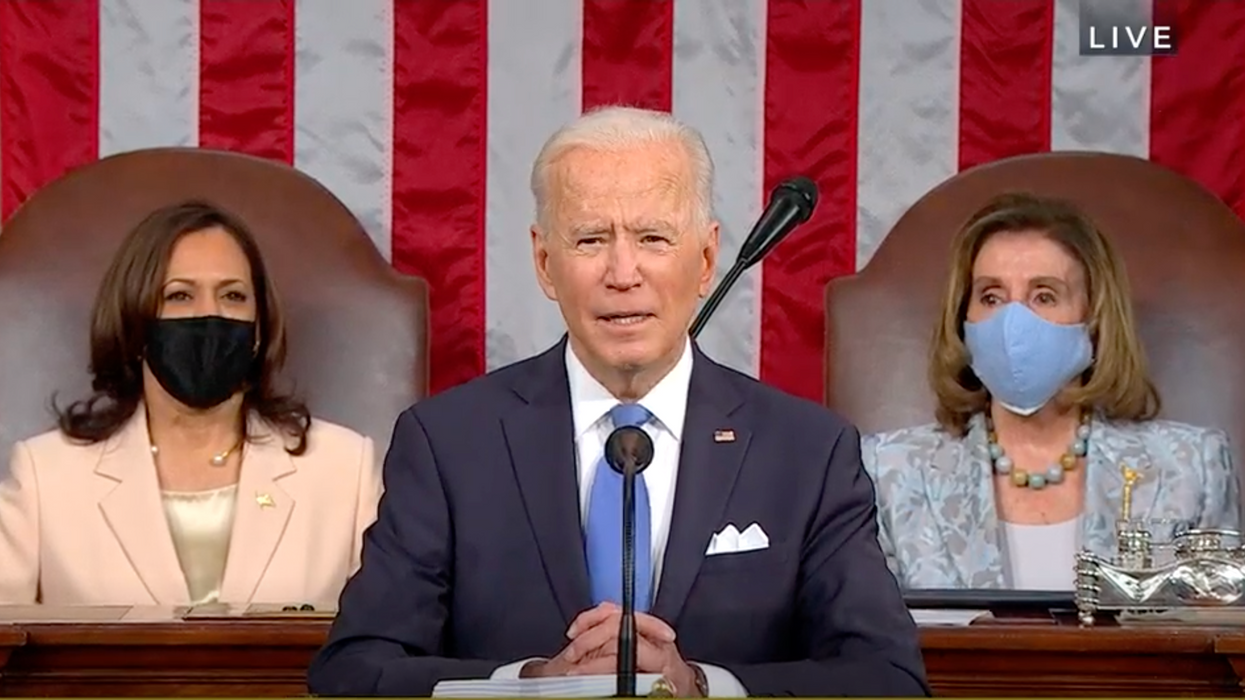

Biden’s Big History Lesson For Republicans

Embedded in Joe Biden's first speech to Congress was a crucial lesson in our nation's economic history that every American ought to understand.

Explaining why he proposes to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on the construction of new power grids, broadband internet connections and transportation systems, the president reminded us of the public investments that have "transformed America" into a prosperous world power. It is a lesson too often and too easily forgotten amid the incessant propaganda, imbibed by almost all of us from an early age, about the "magic of the free market," the "dead hand of government" and various equally hoary conservative cliches.

Markets are marvelous, but government has been essential in growing and regulating the economy from the republic's very beginning. Biden cited the transcontinental railroad and the interstate highway system, the construction of public schools and colleges that enabled universal education, the medical and scientific advances that sprang from the space program and defense industries - but his speech could well have continued for quite a while in that same vein. Political leaders from Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln to Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy all have promoted public investment in research, infrastructure and people as the prerequisites of progress, and sometimes even national survival.

What progress requires, however, changes in every generation along with technology and society. Today, we face rapid climate change that jeopardizes the future of human civilization, creating threats that range from flood and fire to pandemic, famine, drought and mass migration. We must swiftly rebuild our basic infrastructure, which is crumbling after decades of neglect. And we have to bring the entire country into the modern digital economy before inequality permanently damages our democracy.

When Republicans say Biden wants to spend too much on a "liberal wish list" and we should do nothing more than repave roads and repair bridges, because that's "real infrastructure," their complaints only expose their ignorance. The expansion of rural broadband is just as necessary as fixing a bridge on a country road, and the replacement of lead pipes in city water systems is just as critical as filling potholes on an urban highway. The long list of projects enumerated in Biden's proposal, from new schools to veterans hospitals, from upgrading water systems to capping old oil and gas wells, and yes, for providing child and elder care — these are harbingers of a future that works.

We ought to have started this transformation years ago, even before the former guy uttered his false promises about infrastructure. But interest rates are still low — and more importantly, the billionaires whose fortunes derive from public investment can certainly pay for its upkeep and expansion. Biden correctly observed that while most Americans suffered from lost jobs and income during the pandemic, the richest families saw their wealth increase by a trillion dollars, after pocketing a Trump tax cut that awarded them trillions more. Are we all in this together? Not unless the super-rich pay their fair share.

It's nice that some Republicans — though not all, apparently — understand that we can't just let everything fall apart because we don't like taxes or we distrust government. Unfortunately, their comprehension of what infrastructure means is quaintly out of date. While the president warmly welcomed Republican proposals because he's interested in achieving a measure of bipartisan agreement, what they have offered so far is absurdly inadequate.

So, he offered a clear warning as well. Doing nothing — like the Republicans and their incompetent leader over the past four years — is not an option.

To find out more about Joe Conason and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.