Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

By Lizzie Presser, Andrea Suozzo, Sophie Chou and Kavitha Surana

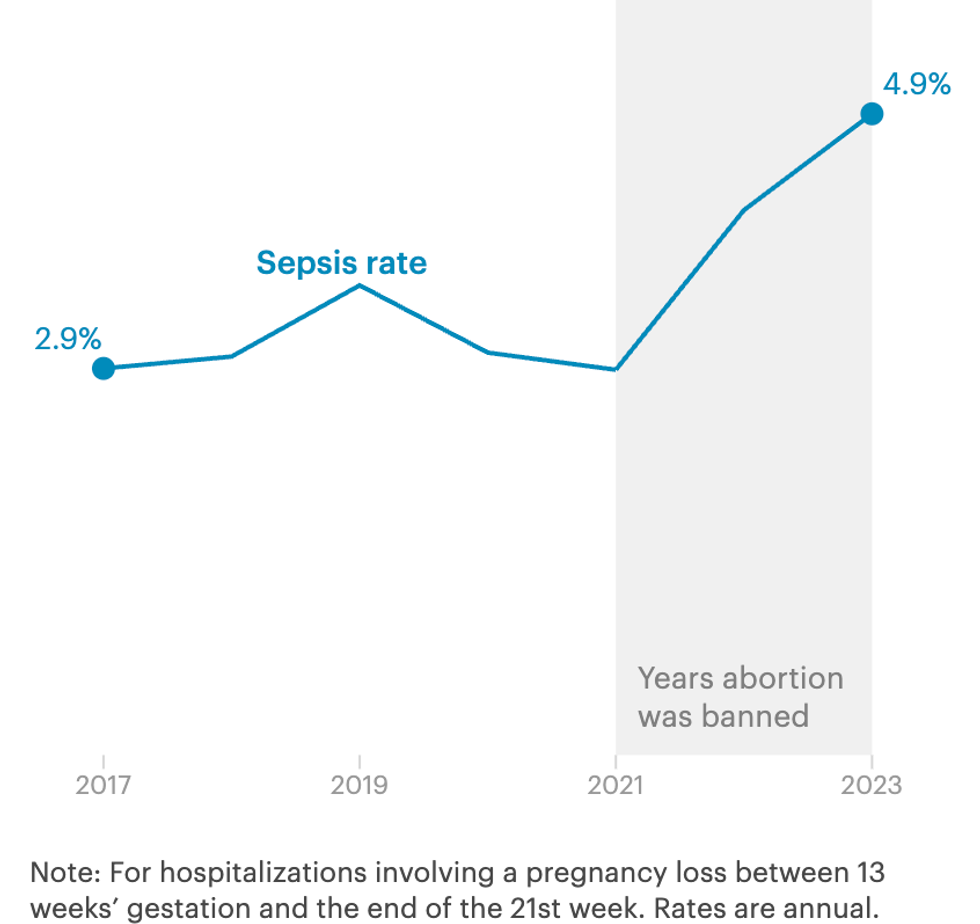

Pregnancy became far more dangerous in Texas after the state banned abortion in 2021, ProPublica found in a first-of-its-kind data analysis.

The rate of sepsis shot up more than 50 percent for women hospitalized when they lost their pregnancies in the second trimester, ProPublica found.

The surge in this life-threatening condition, caused by infection, was most pronounced for patients whose fetus may still have had a heartbeat when they arrived at the hospital.

ProPublica previously reported on two such cases in which miscarrying women in Texas died of sepsis after doctors delayed evacuating their uteruses. Doing so would have been considered an abortion.

The new reporting shows that, after the state banned abortion, dozens more pregnant and postpartum women died in Texas hospitals than had in pre-pandemic years, which ProPublica used as a baseline to avoid COVID-19-related distortions. As the maternal mortality rate dropped nationally, ProPublica found, it rose substantially in Texas.

ProPublica’s analysis is the most detailed look yet at a rise in life-threatening complications for women losing a pregnancy after Texas banned abortion. It raises concerns that the same pattern may be occurring in more than a dozen other states with similar bans.

To chart the scope of pregnancy-related infections, ProPublica purchased and analyzed seven years of Texas’ hospital discharge data.

When abortion was legal in Texas, the rate of sepsis for women hospitalized during second-trimester pregnancy loss was relatively steady. Then the state’s first abortion ban went into effect and the rate of sepsis spiked.

Chart via Pro Publica

Chart via Pro Publica

“This is exactly what we predicted would happen and exactly what we were afraid would happen,” said Dr. Lorie Harper, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Austin.

She and a dozen other maternal health experts who reviewed ProPublica’s findings say they add to the evidence that the state’s abortion ban is leading to dangerous delays in care. Texas law threatens up to 99 years in prison for providing an abortion. Though the ban includes an exception for a “medical emergency,” the definition of what constitutes an emergency has been subject to confusion and debate.

Many said the ban is the only explanation they could see for the sudden jump in sepsis cases.

The new analysis comes as Texas legislators consider amending the abortion ban in the wake of ProPublica’s previous reporting, and as doctors, federal lawmakers and the state’s largest newspaper have urged Texas officials to review pregnancy-related deaths from the first full years after the ban was enacted; the state maternal mortality review committee has, thus far, opted not to examine the death data for 2022 and 2023.

The standard of care for miscarrying patients in the second trimester is to offer to empty the uterus, according to leading medical organizations, which can lower the risk of contracting an infection and developing sepsis. If a patient’s water breaks or her cervix opens, that risk rises with every passing hour.

Sepsis can lead to permanent kidney failure, brain damage and dangerous blood clotting. Nationally, it is one of the leading causes of deaths in hospitals.

While some Texas doctors have told ProPublica they regularly offer to empty the uterus in these cases, others say their hospitals don’t allow them to do so until the fetal heartbeat stops or they can document a life-threatening complication.

Last year, ProPublica reported on the repercussions of these kinds of delays.

Forced to wait 40 hours as her dying fetus pressed against her cervix, Josseli Barnica risked a dangerous infection. Doctors didn’t induce labor until her fetus no longer had a heartbeat.

Physicians waited, too, as Nevaeh Crain’s organs failed. Before rushing the pregnant teenager to the operating room, they ran an extra test to confirm her fetus had expired.

Both women had hoped to carry their pregnancies to term, both suffered miscarriages and both died.

In response to their stories, 111 doctors wrote a letter to the Legislature saying the abortion ban kept them from providing lifesaving care and demanding a change.

“It’s black and white in the law, but it’s very vague when you’re in the moment,” said Dr. Tony Ogburn, an OB-GYN in San Antonio. When the fetus has a heartbeat, doctors can’t simply follow the usual evidence-based guidelines, he said. Instead, there is a legal obligation to assess whether a woman’s condition is dire enough to merit an abortion under a prosecutor’s interpretation of the law.

Some prominent Texas Republicans who helped write and pass Texas’ strict abortion bans have recently said that the law should be changed to protect women’s lives — though it’s unclear if proposed amendments will receive a public hearing during the current legislative session.

ProPublica’s findings indicate that the law is getting in the way of providing abortions that can protect against life-threatening infections, said Dr. Sarah Prager, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington.

“We have the ability to intervene before these patients get sick,” she said. “This is evidence that we aren’t doing that.”

A New View

Health experts, specially equipped to study maternal deaths, sit on federal agencies and state-appointed review panels. But, as ProPublica previously reported, none of these bodies have systematically assessed the consequences of abortion bans.

So ProPublica set out to do so, first by investigating preventable deaths, and now by using data to take a broader view, looking at what happened in Texas hospitals after the state banned abortion, in particular as women faced miscarriages.

“It is kind of mindblowing that even before the bans researchers barely looked into complications of pregnancy loss in hospitals,” said perinatal epidemiologist Alison Gemmill, an expert on miscarriage at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

In consultation with Gemmill and more than a dozen other maternal health researchers and obstetricians, ProPublica built a framework for analyzing Texas hospital discharge data from 2017 to 2023, the most recent full year available. This billing data, kept by hospitals and collected by the state, catalogues what happens in every hospitalization. It is anonymized but remarkable in its granularity, including details such as gestational age, complications and procedures.

To study infections during pregnancy loss, ProPublica identified all hospitalizations that included miscarriages, terminations and births from the beginning of the second trimester up to 22 weeks’ gestation, before fetal viability. Since first-trimester miscarriage is often managed in an outpatient setting, ProPublica did not include those cases in this analysis.

When looking at stays for second-trimester pregnancy loss, ProPublica found a relatively steady rate of sepsis before Texas made abortion a crime. In late 2021, the state made it a civil offense to end a pregnancy after a fetus developed cardiac activity, and in the summer of 2022, the state made it a felony to terminate any pregnancy, with few exceptions.

In 2021, 67 patients who lost a pregnancy in the second trimester were diagnosed with sepsis — as in the previous years, they accounted for about three percent of the hospitalizations.

In 2022, that number jumped to 90.

The following year, it climbed to 99.

ProPublica’s analysis was conservative and likely missed some cases. It doesn’t capture what happened to miscarrying patients who were turned away from emergency rooms or those like Barnica who were made to wait, then discharged home before they returned with sepsis.

Our analysis showed that patients who were admitted while their fetus was still believed to have a heartbeat were far more likely to develop sepsis.

“What this says to me is that once a fetal death is diagnosed, doctors can appropriately take care of someone to prevent sepsis, but if the fetus still has a heartbeat, then they aren’t able to act and the risk for maternal sepsis goes way up,” said Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UW Medicine and an expert in pregnancy complications. “This is needlessly putting a woman’s life in danger.”

Studies indicate that waiting to evacuate the uterus increases rates of sepsis for patients whose water breaks before the fetus can survive outside the womb, a condition called previable premature rupture of membranes or PPROM. Because of the risk of infection, major medical organizations like the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advise doctors to always offer abortions.

Researchers in Dallas and Houston examined cases of previable pregnancy complications at their local hospitals after the state ban. Both studies found that when women weren’t able to end their pregnancies right away, they were significantly more likely to develop dangerous conditions than before the ban. The study of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, not yet published, found that the rate of sepsis tripled after the ban.

Dr. Emily Fahl, a co-author of that study, recently urged professional societies and state medical boards to “explicitly clarify” that doctors need to recommend evacuating the uterus for patients with a PPROM diagnosis, even with no sign of infection, according to MedPage Today.

UTHealth Houston did not respond to several requests for comment.

ProPublica zoomed out beyond the second trimester to look at deaths of all women hospitalized in Texas while pregnant or up to six weeks postpartum. Deaths peaked amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and most patients who died then were diagnosed with the virus. But looking at the two years before the pandemic, 2018 and 2019, and the two most recent years of data, 2022 and 2023, there is a clear shift:

In the two earlier years, there were 79 maternal hospital deaths.

In the two most recent, there were 120.

Caitlin Myers, an economist at Middlebury College, said it’s crucial to examine these deaths from different angles, as ProPublica has done. Data analyses help illuminate trends but can’t reveal a patient’s history or wishes, as a detailed medical chart might. Diving deep into individual cases can reveal the timeline of treatment and how doctors behave. “When you see them together, it tells a really compelling story that people are dying as a result of the abortion restrictions.”

Texas has no plans to scrutinize those deaths. The chair of the maternal mortality review committee said the group is skipping data from 2022 and 2023 and picking up its analysis with 2024 to get a more “contemporary” view of deaths. She added that the decision had “absolutely no nefarious intent.”

“The fact that Texas is not reviewing those years does a disservice to the 120 individuals you identified who died inpatient and were pregnant,” said Dr. Jonas Swartz, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University. “And that is an underestimation of the number of people who died.”

The committee is also prohibited by law from reviewing cases that include an abortion medication or procedure, which can also be used during miscarriages. In response to ProPublica’s reporting, a Democratic state representative filed a bill to overturn that prohibition and order those cases to be examined.

Because not all maternal deaths take place in hospitals and the Texas hospital data did not include cause of death, ProPublica also looked at data compiled from death certificates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It shows that the rate of maternal deaths in Texas rose 33% between 2019 and 2023 even as the national rate fell by 7.5%.

A New Imperative

Texas’ abortion law is under review this legislative session. Even the party that championed it and the senator who authored it say they would consider a change.

On a local television program last month, Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick said the law should be amended.

“I do think we need to clarify any language,” Patrick said, “so that doctors are not in fear of being penalized if they think the life of the mother is at risk.”

State Sen. Bryan Hughes, a Republican who once argued that the abortion ban he wrote was “plenty clear,” has since reversed course, saying he is working to propose language to amend the ban. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott told ProPublica, through a spokesperson, that he would “look forward to seeing any clarifying language in any proposed legislation from the Legislature.”

Patrick, Hughes and Attorney General Ken Paxton did not respond to ProPublica’s questions about what changes they would like to see made this session and did not comment on findings ProPublica shared.

In response to ProPublica’s analysis, Abbott’s office said in a statement that Texas law is clear and pointed to Texas health department data that shows 135 abortions have been performed since Roe was overturned without resulting in prosecution. The vast majority of the abortions were categorized as responses to an emergency but the data did not specify what kind. Only five were solely to “preserve [the] health of [the] woman.”

At least seven bills related to repealing or creating new exceptions to the abortion laws have been introduced in Texas.

Doctors told ProPublica they would most like to see the bans overturned so all patients could receive standard care, including the option to terminate pregnancies for health considerations, regardless of whether it’s an emergency. No list of exceptions can encompass every situation and risk a patient might face, obstetricians said.

“A list of exceptions is always going to exclude people,” said Dallas OB-GYN Dr. Allison Gilbert.

It seems unlikely a Republican-controlled Legislature would overturn the ban. Gilbert and others are advocating to at least end criminal and civil penalties for doctors. Though no doctor has been prosecuted for violating the ban, the mere threat of criminal charges continues to obstruct care, she said.

In 2023, an amendment was passed that permitted physicians to intervene when patients are diagnosed with PPROM. But it is written in such a way that still exposes physicians to prosecution; it allows them to offer an “affirmative defense,” like arguing self-defense when charged with murder.

“Anything that can reduce those severe penalties that have really chilled physicians in Texas would be helpful,” Gilbert said. “I think it will mean that we save patients’ lives.”

Rep. Mihaela Plesa, a Democrat from outside Dallas who filed a bill to create new health exceptions, said that ProPublica’s latest findings were “infuriating.”

She is urging Republicans to bring the bills to a hearing for debate and discussion.

Last session, there were no public hearings, even as women have sued the state after being denied treatment for their pregnancy complications. This year, though some Republicans appeared open to change, others have gone a different direction.

One recently filed a bill that would allow the state to charge women who get an abortion with homicide, for which they could face the death penalty.

Chart via Pro Publica

Chart via Pro Publica