DeSantis 'Election Police' Abuses Are Costly To Democracy -- And Florida

Earlier this month, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement arrested 20 people for election fraud. These 20 people have criminal records that made them ineligible to vote.

Gov. Ron DeSantis announced the charges to show how the first election fraud office in the country was going to work. Even for good faith efforts to participate in democracy as citizens, the defendants, DeSantis said, would “pay the price.”

Not many more will pay, and that’s a problem of DeSantis’ own design.

Back in 2018, the same Florida voters who put DeSantis into office approved a ballot measure called Amendment 4. The Republican DeSantis squeaked out a victory by four tenths of a percentage point margin but sixty-five percent of Sunshine State voters wanted people with felony records, except those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense, to be able to vote when they completed their sentences, including prison, parole and probation.

Amendment 4 had a short life because no one had formally defined what it meant to complete one’s sentence. The Florida Legislature passed Senate Bill 7066 which formally codified the end of a defendant’s sentence; it isn’t over when it’s over. It’s done when he or she pays off all debt incurred by their criminal case and incarceration/supervision.

The law required anyone with a felony record to pay all outstanding fines and fees associated with their conviction before they could vote. Amendment 4 had re-enfranchised 1.4 million people. The imposition of this debt extinguishment requirement took 774,000 people off the list as of late October 2020; they owed money.

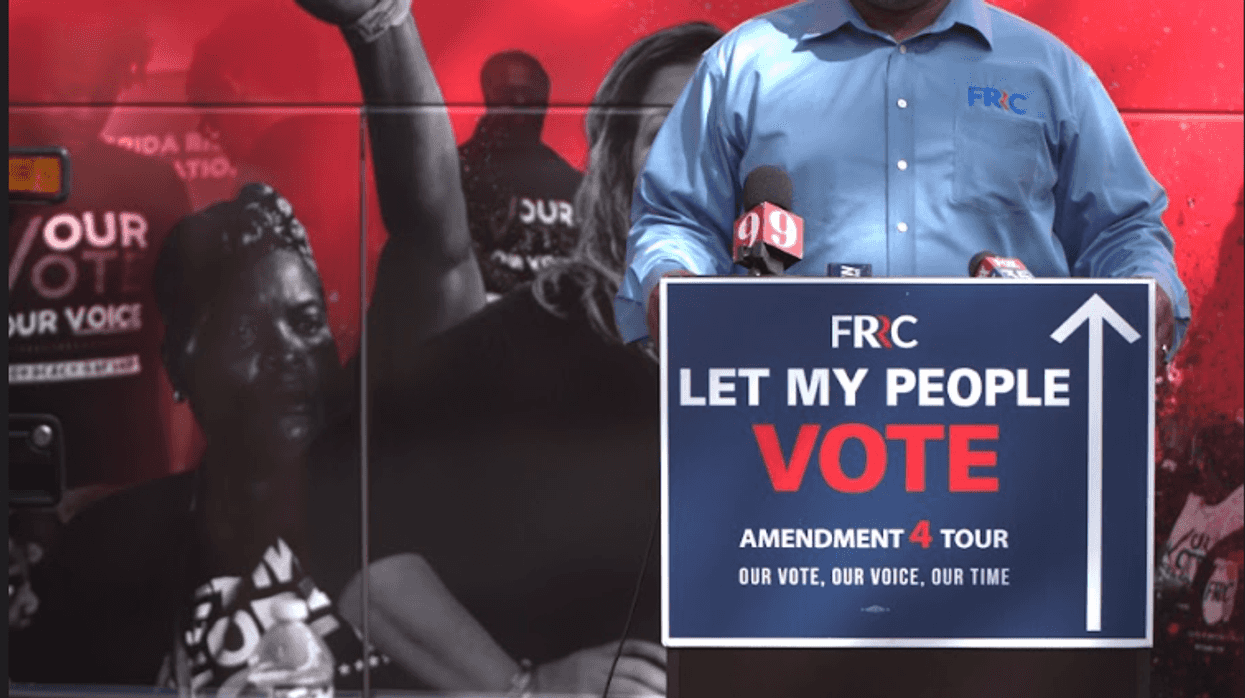

Experts called it a modern day poll tax, an assessment prohibited by the 24th Amendment, passed in 1964. The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC), an organization that had worked to get Amendment 4 on the ballot for six years prior to the November 2018 election, litigated the constitutionality of the statute.

But it didn’t work. On September 11, 2020, 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that it wasn’t unconstitutional; the Supreme Court of the United States had already refused to vacate the 11th Circuit judges’ stay on Amendment 4’s implementation as they finalized their opinion. The highest court’s unwillingness to get involved made the 11th Circuit’s assessment of Amendment 4 final.

There’s a little secret about the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition; the organization possibly singlehandedly saved Florida’s county court systems during the early stages of the pandemic.

“We've seen reports where, collectively, court systems in the state of Florida have been forced to either reduce the salary or lay off 57 percnt of personnel who work within the court system,” Desmond Meade, the founder of Florida Rights Restoration said at a press conference on October 5, 2020 in Tampa, Florida.

Dade County got $7 million from FRRC. Brevard County was looking for a quick fix to a $500,000 deficit when the FRRC appeared with a check for $551,000. Lee County, Florida underwent a $601,000 cash infusion. Palm Beach County recouped a cool $1 million from the voting rights campaign.

Overall, more than $25 million entered the coffers of various Florida counties in 2020. Normally, only about 20 percent of these fines and fees connected to felony cases are collected — and that’s in the good years with no lockdowns, quarantines, or mass unemployment.

During the pandemic that closed courts and caused fewer criminal charges to be filed, even less was going to be collected until the election came around and FRRC started picking up tabs.

Ultimately, FRRC wrote checks to pay people’s legal financial obligations in 60 of the 67 counties in the state of Florida. Pat Frank, the Clerk of Hillsborough County, waived the fines and fees — except for restitution orders — for anyone owing $2200 or less. Ms. Frank reduced the remaining debts by much as 40 percent. The $771,353 that FRRC delivered to Hillsborough County was expected to allow as many as 841 aspiring voters to register to cast a ballot.

How it worked is that FRRC prepaid the money which allowed anyone who came in to register to have their debts paid by the fund. They had to work that way to get as many people paid as quickly as possible. As a result, they got more money into government hands than they got voters to polls; only about 80,000 people with felony convictions registered to vote in 2020, according to reporting from The Miami Herald, Tampa Bay Times, and ProPublica.

It’s a great human interest story that some people with felony records were unsung pandemic heroes. But the story isn’t all rosy; relying on fines and fees isn’t a great way to govern. For one, collection is expensive. Some agencies spend more money chasing checks than they get from cashing them. Florida counties are required to turn unpaid balances to collection agencies after 90 days so even more fees and costs pile up — for counties.

That it’s not ideal doesn’t make state and municipal governments’ reliance on fines and fees any less real.

Nathan Link, assistant professor of criminal justice at Rutgers University and expert on the use of fines and fees in the criminal legal system, says some departments and agencies wouldn’t be able to operate without their clients’ fees supporting them

"We just got an email from a probation chief in Pennsylvania in one of the counties, and they had all of the information on how much revenue they bring in annually based on fees that apply to people on probation or parole. It's a lot. I mean, one of the counties is over $1,000,000 a year and has been $1,000,000 a year, and that is a substantial chunk of that agency's operating budget,” Link said

If the government doesn’t need to fund itself, fiscal considerations can’t cool heads. “I think making the government pay for it when it wants to arrest us and take away our liberties is important because it sort of keeps a check on the government,” Link continued.

As DeSantis and his election squad proved with their opening act — perp walking people who believed they could legally register and vote — there won’t be much of a check on such abuses and, as a result, fewer people with felony convictions will even dare to consider voting. Formerly incarcerated people will be slow to visit the county clerk’s office to register and they’ll avoid polling places entirely. Many experts think that’s been the plan all along.

But there’s a secondary effect to that; they won’t be incentivized to pay off their own obligations like they may be now, if they can afford it. And FRRC isn’t likely to be the hero again and sport them the money. 2020 was different; it was the first national election after Florida residents approved Amendment 4, a particularly contentious election that happened during a public health and economic crisis.

The 2022 midterm elections and the presidential contest in two years may be just as contentious but FRRC knows that the money may have made it possible for people to register but it didn’t necessarily get them to vote. While FRRC hasn’t stopped their campaign to re-enfranchise all systems-impacted people in Florida, they’re expanding their vision for change.

Celebrating the coalition’s tenth anniversary this weekend in Orlando, breakout groups will focus on three core issues: education, employment, and housing; voting rights isn’t at the top of the discussion. They’re seeking bang for their bucks, and not the kind Gov. DeSantis wants to go out with. Those 20 arrests mean DeSantis is leaving millions on the table that could otherwise benefit the people of Florida.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.