President Donald Trump displays his list of "reciprocal tariffs"

In the fall of 1979, as I was just beginning my teaching career at MIT, I went to an economics conference in Vermont. I made the trip in a state of high anxiety — not because I was worried about my presentation, but because I was driving. And it wasn’t at all clear whether I’d be able to find gas for the return trip.

For those were the days of fuel shortages and gas lines, with drivers sometimes waiting hours for the opportunity to refill their tanks.

What happened in 1979 was that the United States faced an inflationary shock: soaring oil prices in the aftermath of the Iranian revolution. That was a bad thing for American consumers. But the experience was made much worse by botched policy. Rather than simply accept higher prices at the pump, the U.S. government imposed a gasoline price ceiling. And as often happens when the government tries to control prices, the result was shortages and a lot of disruption.

Obligatory disclaimer: Price controls, or more generally government pressure on companies to keep prices down, aren’t always a bad thing. Back in 1962, when John F. Kennedy pressured the steel industry to roll back a coordinated price increase, his actions made sense: Steel companies weren’t responding to higher costs, they were collaborating to take advantage of monopoly power.

But trying to simply order businesses not to pass on a genuine cost shock is asking for trouble. Which brings us, as most things seem to these days, to Donald Trump.

Right now U.S. business is facing a large cost shock created by Trump himself. Even after the partial climbdown last weekend, the average U.S. tariff rate stands at 17.8 percent, up 15 points from its pre-Trump level. Since imports of goods are more than 11 percent of GDP, that’s a big shock to consumer prices. And no, foreigners won’t pay the tariffs.

Now, an inflationary hit this size is a bad thing. Still, it could be a one-time event, something the economy absorbs before moving on. But for that to happen we’d need an intelligent, responsible policy response.

Hehehe.

What we’re actually going to get are the three Ds: denial, dirigisme and deception.

Denial: Trump has, of course, repeatedly insisted that there is no inflation in America, pronouncing reports of rising prices “fake news.” What’s new is that Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary — who was, you may remember, supposed to be the adult in the room — has gotten into the act. On Meet the Press Sunday, Bessent dismissed inflation concerns by asserting that

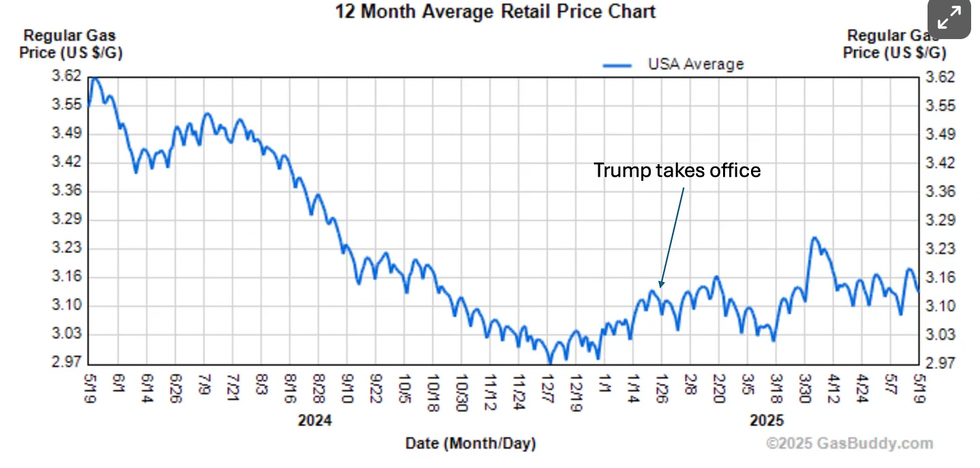

Gasoline prices have collapsed under President Trump … that is a direct tax cut for consumers.

Now, in general presidents deserve neither credit nor blame for fluctuations in gasoline prices, which mainly reflect the global price of crude oil. But that aside, what the heck is Bessent talking about? Here’s what has been happening to gas prices:

Source: Gasbuddy.com

I do not think that word “collapsed” means what he thinks it means.

So is Bessent just lying? Or has he joined Trump in his epistemic bubble, where reality is what he wants it to be? I’m not sure which is worse.

Dirigisme: Originally a term from postwar France, it refers to an economy that remains mostly in private hands but in which the government sometimes tries to tell companies what to do. It remains unclear to this day how well dirigisme actually worked or even how much it was real as opposed to officials getting in front of an economic parade that was happening anyway and pretending that they were leading it. What’s true is that dirigisme may not do too much harm when practiced by sophisticated, well-informed technocrats.

What won’t be harmless is when dirigisme is practiced by a president who takes time off from declaring that Taylor Swift is “no longer hot” to issue demands like this: Now, Walmart, while profitable, can’t actually afford to EAT THE TARIFFS. (Weren’t the Chinese supposed to do that?) So what will Walmart and other companies do if Trump’s tariffs are way up but they’re afraid to risk Trump’s ire by increasing prices?

Hello, empty shelves.

Finally, deception: What will happen when the tariffs start showing up in official measures of inflation, which will happen soon? Erica Groshen, former head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is worried. In a recent briefing paper she warned that changes in personnel policy

could lead to the politicization of the federal statistical workforce … for example, Bureau of Labor Statistics’ leaders could be fired for releasing or planning to release jobs or inflation statistics unfavorable to the President’s policy agenda.

So when inflation rises, the Trump administration could simply bully the statistical agencies into claiming that it never happened. You may say that they couldn’t or wouldn’t do such a thing. But so far people downplaying what Trump and co might do have been wrong every time, while the often-mocked alarmists have been consistently right.

The bottom line is that the direct economic consequences of Trump’s tariffs will surely be bad, but his unwillingness to accept the reality of those consequences will probably make them considerably worse.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack, where he now posts almost every day.

Reprinted with permission from Substack.

- Trump's Autocracy Is A Rude Awakening For His Small Business Fans ›

- Republicans Sing Praise Of Trump Tariffs As Economy Spirals ›