As Insurance Costs Surge, GOP No Longer Pretends To Support Universal Coverage

The Trump administration’s wrecking ball has succeeded in shattering one of the core beliefs of centrist health care reformers, which states: Incremental reforms will eventually lead the U.S. to the promised land of health insurance for all—something most advanced industrial nations achieved more than 75 years ago.

Even many Republicans once signed onto the gradualist approach to achieving the goal of universal coverage. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon proposed covering everyone through insurance industry-managed plans. In the 1990s, a Republican-controlled Congress authorized universal coverage for children. Even President Trump in 2017 vowed to replace Obama’s Affordable Care Act with a new plan that would provide “insurance for everyone.” Ultimately, he failed to either release a plan or repeal Obamacare.

But now, for the first time in its history, the U.S. is making a sharp U-turn on the long road to health care for all. The GOP not even pretending that universal coverage is a desirable national goal. It is deliberately raising the ranks of the uninsured.

The One Big Ugly (not Beautiful) Bill signed by the president last July will drive an estimated 17 million people from the insurance rolls by 2034, according to KFF. More than two-thirds of those losses will come from cuts to Medicaid. Half those cuts, which establish bureaucratic roadblocks for obtaining coverage, won’t be reversed even if the Democrats succeed in forcing concessions from the majority party during the shutdown negotiations, which are still underway as of this writing.

Thanks to legislation Democrats passed during Joe Biden’s administration, the national uninsured rate fell last year to 8 percent, which is within hailing distance of universal coverage (generally considered to be five percent or less). Some states are already below that threshold, which might have occurred nationally had not ten Republican-run states, including populous Texas (still 16.4 percent uninsured) and Florida (10.9 percent), refused to expand Medicaid to cover the working poor. That overall rate is certain to rise next year and for the rest of this decade. If no changes are made, it will soar into the mid-teens, nearly to the levels seen before the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Universal coverage doesn’t guarantee Americans will enjoy better health. Nor does it ensure health care will be affordable. However, it is inconceivable that either of those goals can be achieved without universal coverage, which is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for addressing the long-term health care cost crisis affecting most American households.

Step by step

The incrementalist strategy emerged in the wake of President Harry Truman’s failed attempt after World War II to implement a government-run, universal health insurance plan, similar to those adopted by many European countries. Opposition from the American Medical Association, labor unions with their newly negotiated employer-based plans, and a burgeoning health insurance industry doomed the bill.

But calls for universal coverage never ceased. A decade-and-a-half later, with the White House and Congress in Democratic hands after Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 landslide, the government created Medicare and Medicaid for the old, disabled, and poor. In 1997, after the Bill Clinton administration’s significant push for universal coverage failed, a Republican-led Congress included a separate plan for uninsured children in the Balanced Budget Act.

Then, in 2010, with Barack Obama in the White House and the country reeling from the Great Recession, a Democratic Congress passed the Affordable Care Act. It created a subsidized individual market for those without employer coverage; expanded Medicaid to include individuals and families earning up to 137 percent of the poverty level; and began experimenting with a host of delivery system reforms to hold down costs.

However, cost-saving measures cannot be effective unless everyone is in the insurance pool. Uninsured individuals often postpone necessary but non-emergency care. When they become so sick that they must seek care, they show up in emergency rooms, where care is the most expensive, and where their outcomes are usually worse because they waited too long. For their troubles, they are often saddled with unpaid debts.

More uninsured hurts everyone

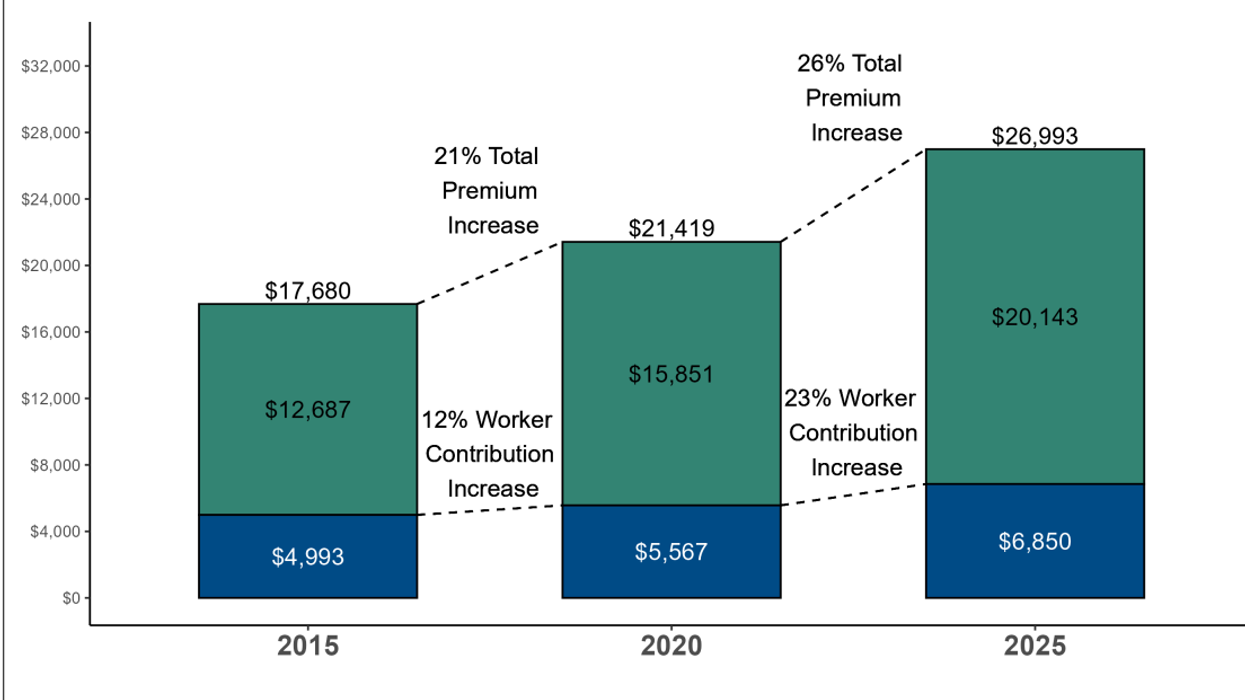

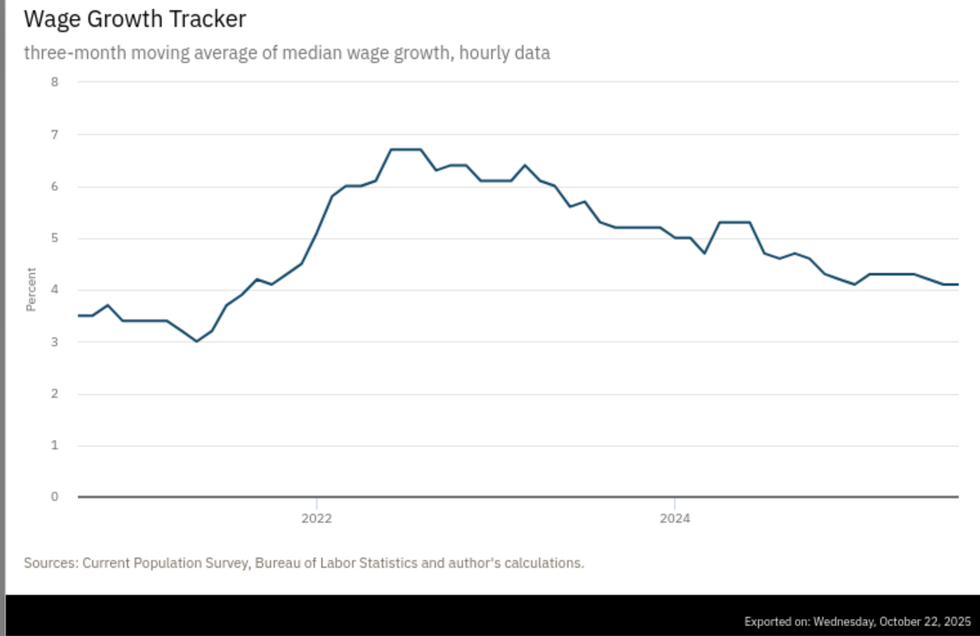

The dysfunction wrought by a growing pool of uninsured people affects everyone’s pocketbook. Providers and insurers use the uninsured’s unpaid bills as an excuse to pass along those expenses in the form of higher prices to the privately insured, who already pay 2 ½ times what Medicare recipients pay on average. This results in not just more expensive plans for employers (the median family plan cost a staggering $27,000 in 2025), but higher co-premiums, co-pays, and deductibles for their employees, whose share of the total cost of “employer-financed” care has hovered between 25 and 30 percent for decades. (I put scare quotes around “employer-financed” because employer contributions are a tax-deductible business expense that otherwise would go to workers as wages if it weren’t spent on benefits.)

Universal coverage doesn’t guarantee that health care will become more affordable for everyone. But it reduces the level of more expensive, uncompensated care in the system, which is necessary to lower prices for everyone, including private insurers and their employer customers. Universal coverage is a crucial prerequisite for achieving more affordable health care.

Yet now, under Trump and a supine Republican Congress, America is deliberately reducing the ranks of the insured. The process has already begun. Premiums for individual plans being sold on the exchanges for next year are soaring due to the expiration of enhanced subsidies, which will discourage many people from buying plans.

Though the bill’s new Medicaid work requirements were postponed until after the 2026 mid-term elections to hide their full effects from voters, states were given the green light to begin enforcing twice-annual recertification requirements. Many red states are already moving to do that, as well as cut their Medicaid spending in response to the cutbacks in federal support for the joint federal-state program. Millions of low-wage workers will start losing their Medicaid coverage next year, not because they aren’t working, but because they become frustrated by the paperwork requirements set up by hostile bureaucrats beholden to their Republican overlords.

Democrats on Capitol Hill are singularly focused on maintaining the enhanced subsidies and restoring the cuts in Medicaid financing. That means the work requirements and other bureaucratic roadblocks will remain because they can’t be addressed in a reconciliation bill. No matter how the shutdown is resolved, a sharp decline in both coverage and access is inevitable.

That will financially harm almost everyone covered by employer-sponsored plans. This year, those rates soared at twice the inflation rate on average, according to the annual KFF employer survey of just under 1,300 firms. Mercer, a leading benefits consulting firm, says rates will rise by a similar level next year. Plan structures will undoubtedly include higher co-payments, higher deductibles, and higher co-premiums for workers and their families.

No matter how the government shutdown is resolved, the health care affordability crisis, exacerbated by the historic GOP U-turn on universal coverage, will remain a salient issue during next year’s House and Senate campaigns. The only question is whether Democrats will be able to take advantage by offering a program that addresses voters’ number one concern when it comes to health care.

This story first appeared on the Washington Monthly website.

Merrill Goozner, the former editor of Modern Healthcare, writes about health care and politics at GoozNews.substack.com, where this column first appeared. Please consider subscribing to support his work.

Reprinted with permission from Gooz News

Source: Atlanta Federal Reserve

Source: Atlanta Federal Reserve