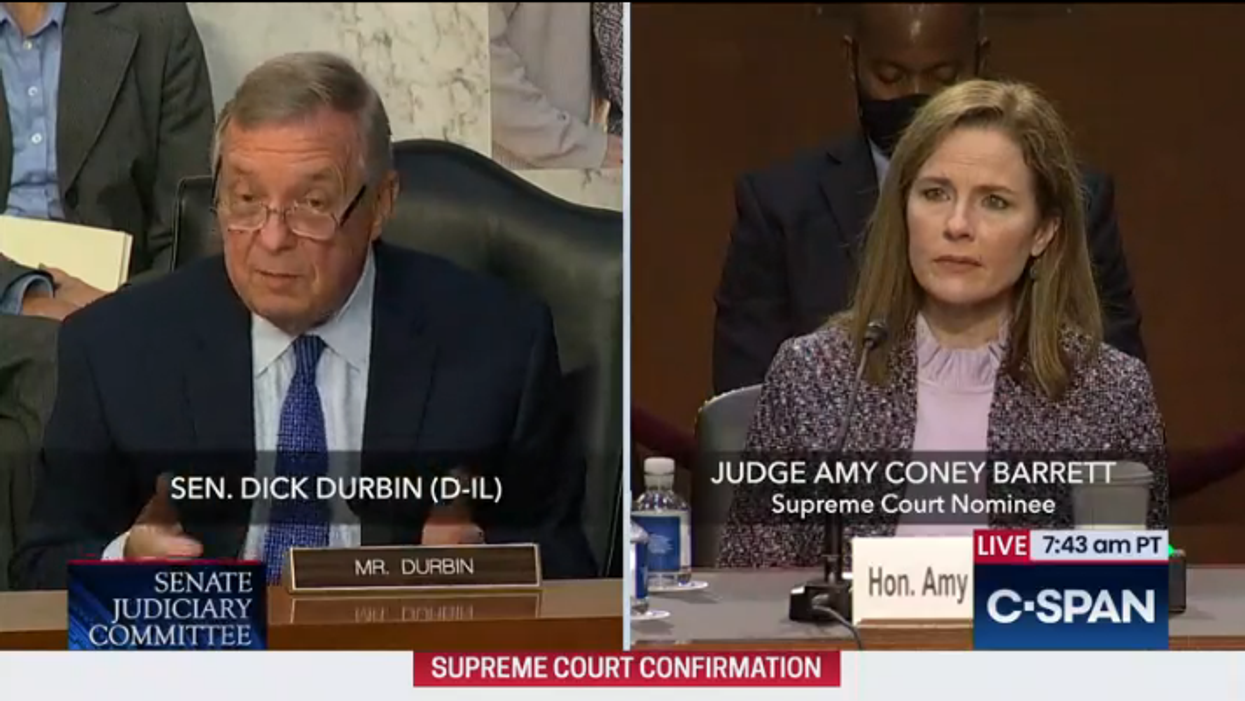

WATCH: Barrett Refuses To Answer Voting Rights Questions

Sen. Dick Durbin and Judge Amy Coney Barrett

On the third day of the Senate Judiciary Committee's hearings on Judge Amy Coney Barrett's nomination to the Supreme Court, Barrett refused to answer yet another question about voting rights, this time posed to her by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL).

"[The] 15th Amendment: The right of citizens in the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged on account of race," Durbin said. "For an originalist and a textualist, that is clear text as I see it, but when asked whether the president has any authority to unilaterally deny that right to a vote to a person based on race or even gender — are you saying you can't answer that question?"

Barrett responded by acknowledging that the Constitution does indeed contain provisions prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race in voting.

"But whether a president can unilaterally deny — you're not going to answer yes or no?" Durbin asked.

Barrett said that Durbin has asked several different questions about what a president might be able to unilaterally do.

"I think that I really can't say anything more than I'm not going to answer hypotheticals," she added.

Durbin pointed out that Barrett would be a "strange originalist" if the "clear wording of the Constitution establishes a right" and she refused to acknowledge it.

"It would strain the canons of conduct, which don't permit me to offer off-the-cuff reactions or any opinions outside of the judicial decision-making process," Barrett replied. "It would strain Article 3, which prevents me from deciding legal issues outside the context of cases and controversies and, as Justice Ginsburg said, it would display disregard for the whole judicial process."

This wasn't the first time during the confirmation hearing process that Barrett refused to answer a voting rights question.

Asked by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) on the second day of the hearing if voter intimidation was prohibited by federal law, Barrett refused to answer, claiming that she couldn't "characterize the facts in a hypothetical situation" or "apply the law to a hypothetical set of facts."

"I can only decide cases as they come to me, litigated by parties on the full record, after fully engaging precedent, talking to colleagues, writing an opinion," Barrett said. "And so I can't answer questions like that."

Also on the second day of the hearing, ranking Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein (CA) asked the SCOTUS nominee whether the Constitution allowed for the general election to be delayed.

"President Trump made claims of voter fraud and suggested he wanted to delay the upcoming election," Feinstein said. "Does the Constitution give the president of the United States the authority to unilaterally delay a general election under any circumstances? Does federal law?"

Barrett again demurred, saying that she would "need to hear arguments with the litigants," read briefs, consult with law clerks and colleagues, and "go through the opinion-writing process."

She added that she wanted to come to these issues with an "open mind" rather than give "off-the-cuff answers" like a pundit.

But the law is clear: Federal statute mandates the 2020 general election date of Nov. 3, and there is no statute allowing for a sitting president to move or delay it.

Barrett's own judicial record gives troubling glimpses of her positions on voting rights.

In Kanter v. Barr, a case decided last year by the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Barrett argued unsuccessfully that the right to bear arms was more fundamental than the right to vote.

The 7th Circuit upheld a lower court's decision that Rickey Canter, who had been convicted of a felony and was barred from owning a firearm by federal and Wisconsin state law, could not purchase a gun.

The vote was 2-1. Of the three sitting judges, Barrett alone dissented.

She penned a 38-page dissent arguing that the Founding Fathers did not intend to prohibit all those convicted of felonies from gun ownership, just those convicted of violent felonies.

In it, she drew a distinction between civic rights and individual rights, arguing that individuals convicted of felonies should be able to own guns (deemed by Barrett an individual right), but not vote (deemed a civic right).

Barrett doubled down on minimizing voting rights later in her dissent, writing that unlike gun rights, the "rights to vote and serve on juries" are rights that belong "only to virtuous citizens."

In another case heard by the 7th Circuit in 2019, Acevedo v. Cook County Officers Electoral Board, Barrett sided with the majority, ruling against a plaintiff running for sheriff who could not appear on a ballot in the primaries due to not having enough signatures.

The county had a threshold of signatures set at 0.5 percent, which in Cook County was more than 8,200 votes. While the candidate had met the state's lower threshold of 5,000 votes, he did not have the number required by the county.

In Acevedo, Barrett applied what's known as Anderson-Burdick balancing, a standard that holds that the government cannot impose "extreme" burdens that impede an individual's right to vote, but that slight burdens might be acceptable if in the interest of the state.

Barrett cited Anderson-Burdick in her opinion, claiming the plaintiff's burdens did not rise to the level of "extreme."

For Barrett, what constitutes an "extreme" burden on voting rights seems to be a high bar to clear.

And, on the cusp of a potentially contested election, it's not hard to imagine that voting questions may come before the Supreme Court that involve the constitutionality of signature matching, notary public requirements, closed polling sites, and limits on drop-off boxes.

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

- Hashtag 'Superspreader' Pinned To Trump's Reckless Supreme ... ›

- WATCH: Barrett Deflects Questions On Roe, Despite Publicly Urging ... ›

- Barrett Wouldn't Say That Voter Intimidation Is a Federal Crime ... ›

- The Vital Questions Our Senators Neglected To Ask Judge Barrett - National Memo ›

- Stunning Split Decision By Supreme Court Upholds Voting Rights — And May Decide 2020 - National Memo ›

- Soiled By Blatant Partisan Bias, Barrett Must Recuse — But Will She? - National Memo ›