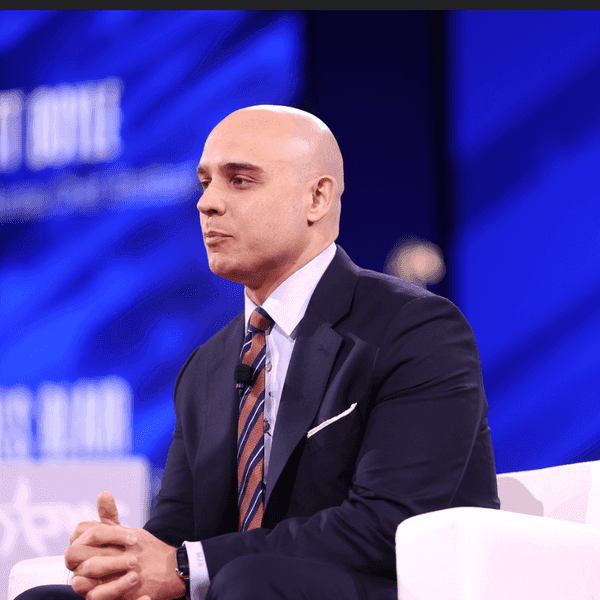

Don Lemon

Editor’s Note: The indictment of Don Lemon is both pernicious and unprecedented. The indictment and the process that led to it implicate both prosecutorial practice and the limits of criminal law. For that reason, this Substack proceeds in two parts. Part One focuses on the process and motives behind the prosecution. Part Two addresses why the charges fail on their own terms and what the case signals for press freedom and the Department of Justice.

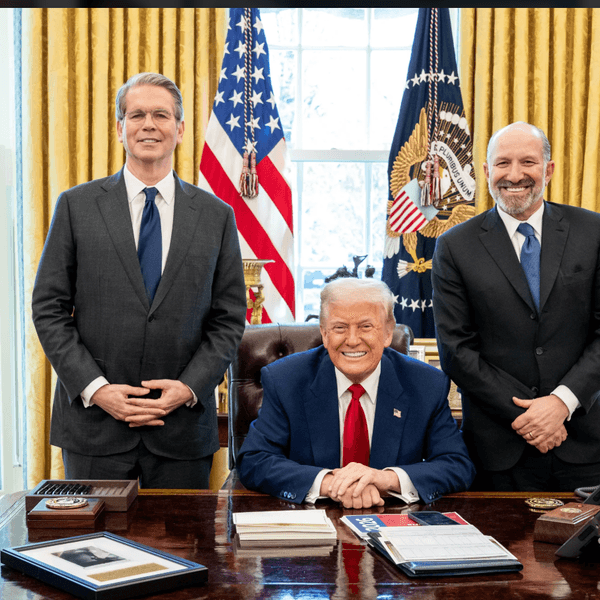

For starters, U.S. attorneys general don’t put their names at the top of federal indictments, as Pam Bondi did on the indictment of Don Lemon filed last Thursday.

That’s just the first in a series of glaring irregularities in the indictment of Don Lemon (and Minnesota local journalist Georgia Fort) last Friday.

That series tends to demonstrate that the prosecution, which career prosecutors advised Bondi against, has nothing to do with the standard work of the Department of Justice. It is something else entirely: a performance, carefully staged by Pam Bondi to impress an audience of one—Donald Trump.

Bondi announced the charges Trump-style on X, explicitly claiming credit for the operation: “At my direction, early this morning, federal agents arrested Don Lemon … in connection with the coordinated attack on Cities Church in St. Paul, Minnesota.”

She reinforced the point in a pre-recorded video statement in which she again claimed the indictment as her own. At the same time as she played to the president, she dodged everyone else: the pre-recorded video ensured she would not have to answer questions, leaving Todd Blanche to stand live in front of the cameras and absorb the blowback.

The AG’s announcements were a second complete departure from DOJ practice. Standard DOJ protocol is for charges to be announced by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the district where they are brought—not by the Attorney General asserting personal operational control. I know of no other case in which the AG has hogged the spotlight.

Bondi followed up Monday morning with a swaggering, tough-talking tweet, complete with Trumpian capital letters: “If you riot in a place of worship, we WILL find you.” The strut was pure phony bravado, and again from a safe distance: what happened in the church is far from what we think of as a riot, and public protesters didn’t try to hide to keep from being found.

Third, Bondi, in her statement, took personal credit for Lemon’s arrest—a ministerial detail that no attorney general would ordinarily concern herself with, let alone advertise. Decisions about whether and when to arrest a defendant are routine operational matters, handled by line prosecutors and agents, not the nation’s chief law-enforcement officer. Except here.

The arrest in fact was a third instance of deviation from the DOJ playbook, and this one particularly petty and vicious. Standard DOJ practice in the case of a public figure of Lemon’s prominence would be to send him a summons and permit him to self-surrender, as happened, for example, after the indictments of Donald Trump. (The one exception that comes to mind was Rudy Giuliani’s roundly criticized practice as U.S. Attorney of forcing white collar criminals such as Michael Milken to do “perp walks.”)

Lemon instead was arrested, late at night, and held long enough to spend the night in jail. There was no law-enforcement rationale for that decision. Lemon posed no conceivable risk of flight, no danger to the community, and no reason to believe he would not appear voluntarily. The obvious explanation is Bondi wanted to humiliate Lemon, and the obvious reason was to please the boss, whose antagonism toward Lemon is well-known and longstanding.

Bondi has been widely reported as having fallen from Trump’s good graces, particularly as the Department of Justice has suffered a string of embarrassing losses in courts around the country. Judicial rebukes, emergency stays, and skeptical bench rulings have undercut the administration’s political priorities. Against that backdrop, a high-visibility prosecution targeting immigration protest, religious worship, and a longtime Trump antagonist offered something else: a show of aggression, loyalty, and resolve—aimed not at persuading judges, but at reassuring a single, volatile audience.

From Bondi’s perspective, the case was irresistible. It checked three boxes that matter deeply to Donald Trump: Minnesota immigration enforcement, religious worship framed as a church under siege, and Don Lemon himself—a prominent journalist and longtime Trump antagonist. A case that combined all three was not merely a prosecution. It was a political trifecta.

The indictment process itself represents another clear break from established practice. According to press reporting, the decision to bring the Lemon case came from the top of the Department, not through the ordinary judgment of the local U.S. Attorney’s Office. Those same reports indicate that career prosecutors raised objections, warning that the charges stretched civil-rights statutes beyond their traditional bounds.

That brings us to the most conspicuous and consequential irregularity of the case: the merits.

The main charge in the indictments of Lemon and Forts (who also was subjected to FBI most-wanted list treatment in her arrest by a squad of FBI and DHS agents) is a violation of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (“FACE”).

FACE was Congress’s response to a sustained campaign of aggressive and often violent blockades of reproductive health clinics by anti-abortion activists in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Across the country, organized groups physically obstructed clinic entrances, chained themselves to doors, blocked driveways, and harassed patients and providers seeking to enter.

These actions were designed to shut clinics down through force and intimidation. Local authorities often proved unable—or unwilling—to respond effectively, and civil remedies offered little deterrence. Congress enacted FACE to fill that gap: to protect access to lawful medical care by targeting force, threats, and physical obstruction, while leaving peaceful protest and expressive activity untouched.

The inclusion of religious worship was also the product of legislative compromise. Adding protection for houses of worship broadened political support for the bill and reinforced that FACE was aimed at coercive interference with constitutionally protected activity rather than at suppressing protest or expression tied to any particular cause. By covering religious practice as well as reproductive health care, Congress sought to ensure access to places of worship against the same forms of coercive interference, while preserving the constitutional line that leaves peaceful protest and expressive activity untouched.

Thus, the problem FACE was designed to address was not protest or offense, but tactical efforts to shut lawful activity down through force, threats, and physical obstruction.

To prove a violation of FACE’s criminal provision, prosecutors must show that the defendant, by force or threat of force or by physical obstruction, intentionally injured, intimidated, or interfered with a person because that person was obtaining or providing religious services.

FACE has an express carve-out for expression. The statute provides that “nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit any expressive conduct (including peaceful picketing or other peaceful demonstration) protected from legal prohibition by the First Amendment.” The Constitution’s protection of speech would, of course, operate anyway, but Congress wanted to emphasize the point.

Courts interpreting the act have consistently emphasized that point in a series of cases in which FACE has survived First Amendment challenges.

Not surprisingly, the paradigm FACE cases involve concerted acts of violence to physically prevent women from gaining access to reproductive health services. They include defendants who locked arms or chained themselves to entrances; physically blocked doors, hallways, or stairwells; refused to move when ordered to do so; or used vehicles or other objects to bar access to buildings. In those cases, the interference with medical services was not merely disruptive or upsetting; it was the very point of the conduct. People could not enter or leave. Services could not continue. And the obstruction itself—not its expressive content—did the work.

Courts have been equally clear about what does not fall within FACE’s reach. Chanting, shouting, leafleting, questioning, filming, and following at a distance—even when aggressive, unwanted, or deeply offensive—do not suffice. The statute does not criminalize protest as such. It criminalizes physical interference. That distinction is what keeps the statute from swallowing the First Amendment. In the second part of this essay, I’ll analyze why the charges in the indictment don’t begin to meet the standard.

Harry Litman is a former United States Attorney and the executive producer and host of the Talking Feds podcast. He has taught law at UCLA, Berkeley, and Georgetown and served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Clinton Administration. Please consider subscribing to Talking Feds on Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Talking Feds.

- Former CNN journalist Don Lemon released following arrest over ... ›

- Bondi Faces Epstein Backlash Over Don Lemon Arrest ›

- Trump administration charges Don Lemon with federal civil rights ... ›

- Pam Bondi's mad after judge rejects charging Don Lemon ›

- At my direction, early this morning federal agents arrested Don ... ›