New Report Sharpens Doubt About Medicare Advantage As Open Enrollment Begins

Open enrollment for the over-65 crowd began yesterday with most analysts predicting there will be a sharp dip in the number of seniors who choose privatized Medicare Advantage plans for 2026.

That’s good news for people worried about the program’s fiscal health and the looming expiration of its trust fund, now slated for 2033. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services paid MA plans an estimated $84 billion more than it would have had the 54 percent of all beneficiaries choosing MA plans in 2025 — the most ever — remained in traditional Medicare, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Why do experts predict many people will opt out next year? In part, it’s because the three major insurers selling MA plans — UnitedHealth, Humana, and CVS Health’s Aetna — have eliminated hundreds of counties, and in some cases, entire states from their plans.

Despite the enormous profits they earn from MA, insurers complain rising prices and greater utilization are driving up their expenses (true) while the federal government is curtailing reimbursement (false). The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services final MA payment rule, unveiled last April, showed private health plans will get an effective rate increase of nine pecent in 2026, which is several percentage points above inflation-adjusted economic growth rate.

Disappearing plans is not the only reason why people are abandoning MA. Consumer preference is playing a huge role.

Private insurers are increasingly using prior authorization to curb utilization. Prior authorization is where physicians are required to obtain insurer approval before making specialist referrals, prescribing certain drugs, tests and procedures, and, in some cases, ordering preventive care. This delay and deny strategy (the first allows insurers to earn money on the float; the second simply cuts expenses) is drawing enormous pushback from physicians and patients, so much so that the industry was forced to announce this past summer it would take steps to ease the approval process — by 2027.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has also been revamping its “star” rating system, which is one of the few tools elderly consumers have for comparing the quality and outcomes of different plans. Insurers sometimes game the system by combining multiple counties from widely dispersed geographic areas into a single plan for star-rating purposes, which gives a false picture to beneficiaries who happen to live in poor-performing counties included in the plan. Insurers must have 94 percent of its MA members in plans rated 4-star or 5-star before getting a five percent bonus payment.

The revamp is having an impact. For instance, in 2024 Humana had 94 percent of its MA plan members in 4- or 5-star rated plans. The changes instituted by CMS (an agency which so far has escaped the scientific quackery and staff cutbacks Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Martin Makary have imposed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, respectively) reduced its 4- and 5-star share to 25 percent this year, according to a story yesterday in Modern Healthcare. Earlier this week, the U.S. District Court in North Texas rejected Humana’s suit challenging the reduction.

Has Medicare Advantage improved quality?

There is still a substantive debate about whether MA has improved quality for its beneficiaries.

The original idea behind Medicare Advantage, which took off in the early 2000s, was that privatization of Medicare would lead to lower costs since the private sector was, allegedly, more efficient. Proponents of MA also argued that replacing fee-for-service reimbursement as deployed by the government in traditional Medicare with privately managed care would lead to higher quality, greater patient satisfaction and, most importantly, better outcomes.

The first argument is demonstrably false. As numerous MedPAC reports have shown, MA hasn’t saved the government a dime. In fact, over the years it has cost the government hundreds of billions of dollars more.

But have we at least gotten better results from all the extra taxpayer money shoveled out to the insurance industry through privatization? Dozens of studies have been conducted over the years testing that question. Proponents of MA, led by the Better Medicare Alliance, an industry front group, cherry pick the literature to claim MA enrollees have fewer hospital readmissions, fewer preventable hospitalizations and reduce the use of high-risk medications among seniors. Privatization opponents like the Center for Medicare Advocacy are equally adamant that quality in MA is at best no different than traditional Medicare, and in some cases worse.

A September 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation report examined 62 studies published since 2016 that compared MA and traditional Medicare based on measures of beneficiary experience, affordability, service utilization, and quality. The report found MA “outperformed traditional Medicare on some measures, such as use of preventive services, having a usual source of care, and lower hospital readmission rates. However, traditional Medicare outperformed [MA] on other measures, such as receiving care in the highest-rated hospitals for cancer care or in the highest-quality skilled nursing facilities and home health agencies.”

Today, the Commonwealth Fund offered a first-of-its-kind comparison study of Medicare performance in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. While comparing traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage wasn’t its focus, and its authors caution against using its findings to highlight quality differences between the two approaches to paying for care, the scorecard’s findings did suggest (based on my analysis) that MA delivers outcomes on key quality measures that are at best equal to traditional Medicare, and sometimes worse.

The overall study looked at 31 measures of access, quality, affordability and population health, derived from the records of both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans. Two of the main quality indicators highlighted in the report were the statewide number of preventable hospitalizations per 1,000 beneficiaries, and what share of seniors on Medicare were prescribed drugs known to be risky or inappropriate for people in their age group.

For the overall score, the study’s authors ranked each state and the District of Columbia for the 31 measures, and then created a composite score. The results were predictable: Vermont, Utah, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Colorado, New Hampshire, Maine and Hawaii were, in order, the eight top-ranked states; starting from the bottom, Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, West Virginia and Alabama brought up the rear.

Those results show that the social determinants of health — statewide wealth and income, food and housing security, low unemployment and the like — drive overall health and therefore health care spending in Medicare. That’s not surprising. How well people fare during their working years will usually determine how well they fare in retirement, which in turn determines how much they will cost Medicare and, ultimately, how long they will live.

“Spending doesn’t always align with outcomes,” said Dr. Joseph Betancourt, president of the Commonwealth Fund. “The states that tend to do well in Medicare performance also tend to do well in our other surveys of broader populations.”

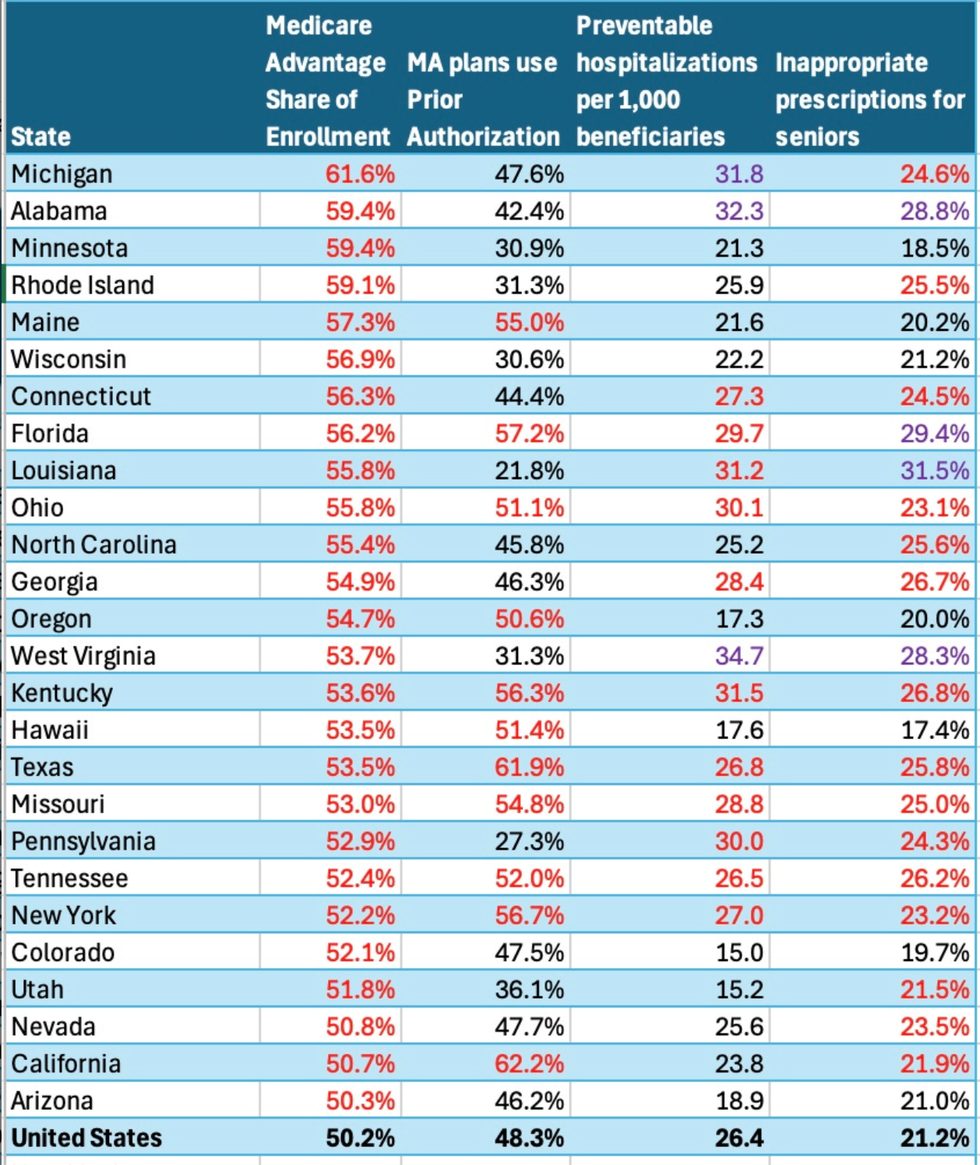

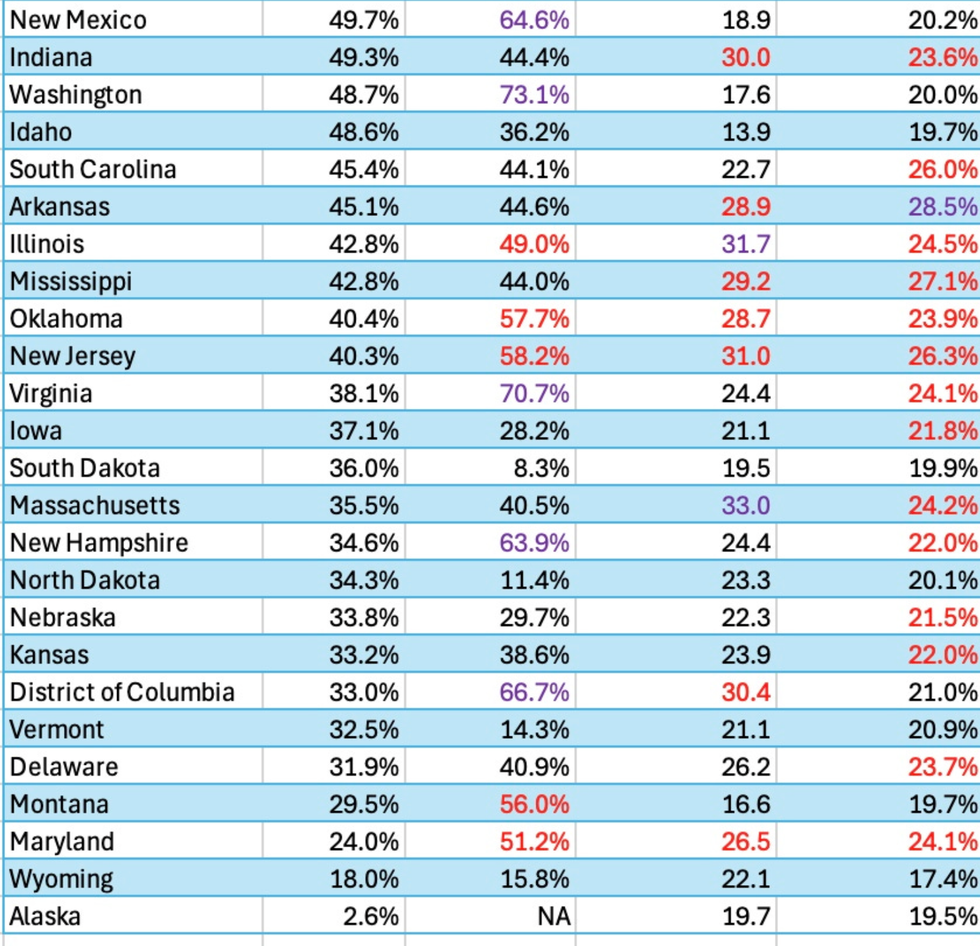

But in looking at the two quality indicators highlighted by the study, a different pattern emerges. I ranked the share of each state’s population in Medicare Advantage plans in 2024 (compiled by the Kaiser Family foundation) and compared that to the state’s performance on two quality indicators: preventable hospitalizations and inappropriate drug prescriptions. In the charts below, the numbers in red and purple (the worse five) are states with below average scores (which are higher numbers); the numbers in black are states that did better (lower numbers) than the national average.

These are important measures for evaluating Medicare Advantage performance since preventing unnecessary hospitalizations is precisely what MA managed care is supposed to achieve and inappropriate prescribing is precisely what MA prior authorization is supposed to prevent. The study also measured what share of MA plans in a state used prior authorization, which is shown in the second column in the chart.

The bottom line: States with above-average enrollment in MA plans tend to have higher-than-average rates of preventable hospitalizations. There is no discernible pattern in the rates of inappropriate prescribing between states with above or below average enrollment in MA plans.

For instance, Michigan ranked in 25th or right in the middle of the pack in the overall rankings. It had the highest Medicare Advantage penetration (61.6 percent). Yet its managed care plans, nearly half of which used prior authorization, did not prevent the state from being ranked fifth worst in preventable hospitalizations and three percentage points above the national average in inappropriate prescribing. Ditto for Alabama, which had the second highest MA market penetration, yet ranked among the five worst when it came to preventing unnecessary hospitalizations and inappropriate prescribing.

On the other end of the spectrum, rural states like Vermont and Wyoming had very low MA market penetration and scant use of prior authorization. Yet they scored above average performance on both quality indicators.

Having read numerous studies over the years that compare Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare, I think it’s fair to say at this point that all the extra money that’s been poured into Medicare Advantage has not delivered to beneficiaries higher quality care or better outcomes. It is, in fact, a waste of money.

I’ll leave the last word to Gretchen Jacobson, the Commonwealth Fund vice president for expanding coverage and access. When it comes to Medicare, the federal government should “set standards for private plans and participating providers” and “incentivize providers to apply best practices and reduce wasteful care.”

Merrill Goozner, the former editor of Modern Healthcare, writes about health care and politics at GoozNews.substack.com, where this column first appeared. Please consider subscribing to support his work.

Reprinted with permission from Gooz News