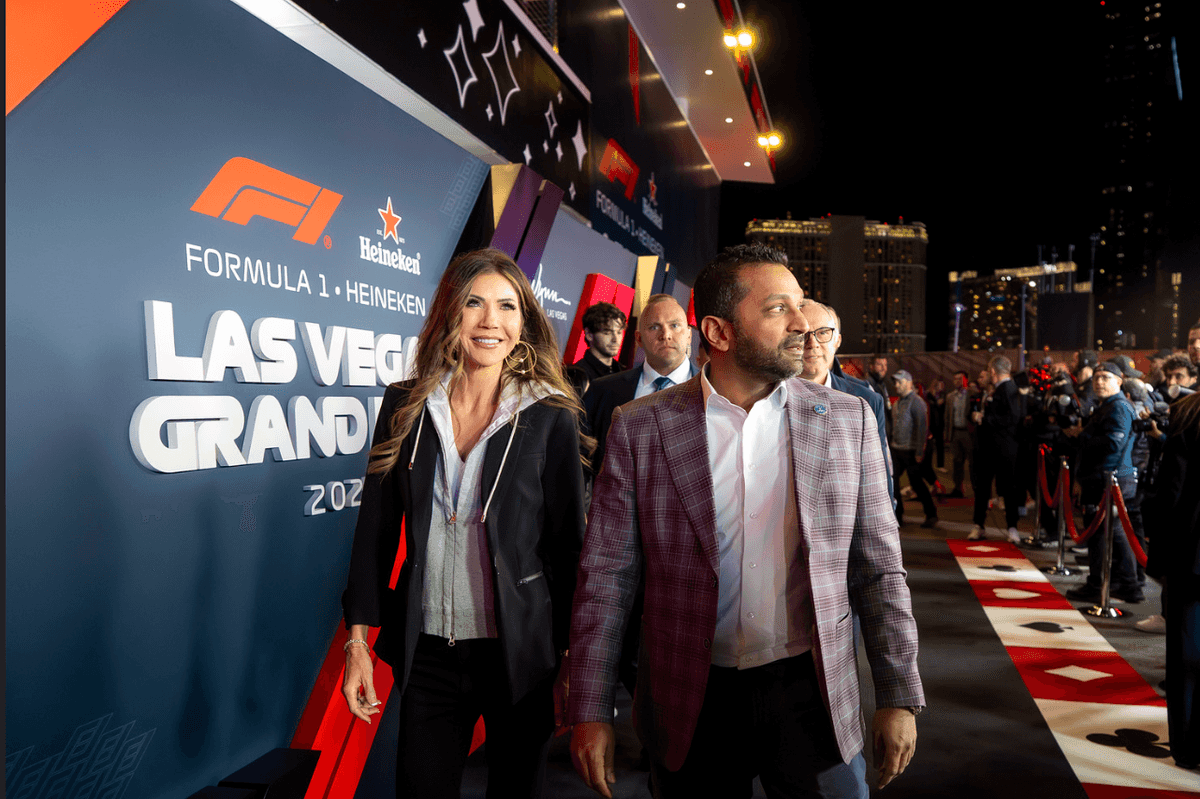

DHS Secretary Kristi Noem and FBI Director Kash Patel visit the Las Vegas Grand Prix on November 25, 2025

The belated dismissal of Kristi Noem – Trump’s woefully unqualified and performatively ridiculous custodian of homeland security --- highlights the perils now faced by all Americans in an increasingly perilous world. Now that the United States is at war with a regime notorious for terror tactics, it is no longer possible to ignore the frightening incompetence of a government that is expected to keep us from harm.

Noem cut an especially clownish figure at the Department of Homeland Security -- with her constant costume changes, soap opera escapades, corrupt expenditures, and abuse of Coast Guard aviation and residential facilities – but the MAGA style of governance is all too visible across our national security agencies.

While it was apparent from the day of her appointment that Noem had no relevant experience or knowledge, she and her “special employee” Corey Lewandowski brought extreme levels of chaos and disrepute to the agencies they oversaw. Like other Trump officials, she imposed senseless waves of cuts, mass firings of veteran officials, useless expenditures, and measures such as polygraph tests that destroyed morale.

And in her zeal to enforce the administration’s absurd deportation schedule, Noem fomented a confrontation with Congress and indeed the entire country that has resulted in the DHS shutdown. With most of its staff forced to work unpaid, all of its security functions are now subject to staffing shortages, rising absences, and declining resolve.

It’s not a good time for that to be going on: The Iranian regime, along with allies in Hezbollah and kindred terror groups, is assuredly seeking means of revenge for the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the wider war. Given Iran’s known capabilities in cyber warfare, the reduced defensive capacity of the DHS-based Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency is troubling.

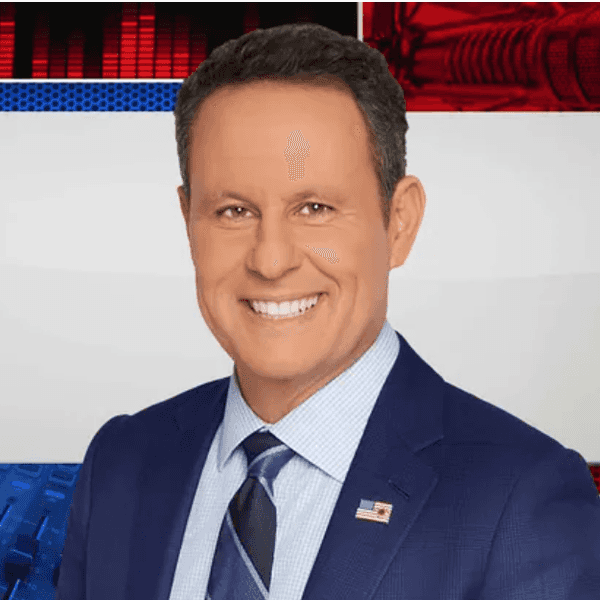

Yet the president has replaced Noem with another politician whose Fox News appearances he enjoys, rather than a serious figure with military, intelligence or even government experience. Oklahoma Sen. Markwayne Mullin may be popular among his peers, but his resume for this position is thinner than paper.

As Kevin Carroll, a former senior DHS official, told CNN on Thursday, ““I'm not sure that Senator Mullin is really qualified. I mean, most of the other secretaries of Homeland Security have had substantial experience in federal law enforcement or the military, or have held senior executive positions… He was a successful, small businessman. But we're in a severe threat environment right now [with the invasion of Iran]. It’s probably the highest threat environment since 9/11 … I really don't think it's time for him to be in his first national security position or his first executive position.”

That disturbing vacuum of professional leadership and skill is reflected throughout Trump’s government, with potentially ruinous consequences. It is especially glaring at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, where the comedy team of Director Kash Patel and former Deputy Director Dan Bongino achieved so much destruction in the span of a few months. Their dismantling of FBI divisions tasked with protecting the country showed a reckless enthusiasm that must have excited our foreign enemies.

Patel has done grave harm to the bureau’s national security branch, which encompasses its divisions of counterterrorism, intelligence and counterintelligence, and its special directorate for weapons of mass destruction – all vital to protecting us at this moment of heightened threats. The FBI cyber division, like CISA at DHS, has likewise suffered from the firings and fear that have destroyed confidence among agents in Washington and in FBI offices around the country and abroad.

The impact of Patel’s recurrent displays of idiocy, arrogance, and abuse are felt far beyond our borders – although the damage has become obvious in major, highly publicized cases like the Brown University murders and the Guthrie abduction. Early in his tenure, at the request of the head of the United Kingdom’s MI5 intelligence agency, Patel agreed to maintain a London FBI station where both countries monitor adversary activities. He violated the pledge almost immediately, earning distrust among the “Five Eyes” intelligence consortium, which includes Australia, Canada, and New Zealand as well as the US and UK and is critical to our counterterrorism effort.

The barely disguised contempt for Patel (and Bongino, whose position was crucial to everyday operations) among foreign security officials is a serious hindrance to the bureau’s international operations division – which depends on our foreign allies to provide actionable information about threats originating overseas.

So toxic is Patel’s presence in the FBI that the bureau may be better off with him spending most of his time far from headquarters, whether at his home in Las Vegas, with his country-singer girlfriend on a government jet, or at the Olympics, car races or other sporting events where he weirdly shows up.

The pattern of dubious political appointees extends into the top levels of every sector, from Tulsi Gabbard at the Directorate of National Intelligence – whom even Trump no longer pretends to respect – to Pete Hegseth at the Pentagon, where security breaches and outright lies have become routine.

Will we pay a hideous price for the misconduct of all these MAGA bozos? In Trump’s second term, America has so far escaped the sort of deadly disaster that arises from stupid, amateurish government -- whether in an intelligence snafu like 9/11 or a botched pandemic response like Covid-19. By now we should know that our luck won't hold forever.

Joe Conason is founder and editor-in-chief of The National Memo. He is also editor-at-large of Type Investigations, a nonprofit investigative reporting organization formerly known as The Investigative Fund. His latest book is The Longest Con: How Grifters, Swindlers and Frauds Hijacked American Conservatism (St. Martin's Press, 2024). The paperback version, with a new Afterword, is now available wherever books are sold.

Reprinted with permission from Creators